Written by Michael Beisty

An Introduction

Disclaimer: Content herein does not constitute specific advice to the reader’s circumstance. It is only an opinion based on my perspective that others may learn from. Anyone of any age who engages in running should be in tune with their body and seek medical advice before embarking on any intensive activity (including changes to said activity) that may unduly extend them. This is critical should the aspiring athlete have underlying medical conditions and/or ongoing health issues requiring medication.

‘Only sport can help in making up for our deficiency in movement and in exercising our bodies. But get this clear: if we take part in sport with the object of putting up good performances, this can only be indulged in if it does not damage our organism and, therefore, our health.’ (Woldemar Gerschler,1954) 1

‘Passive fitness, the mere absence of any illness, is a losing battle. Without activity, the body begins to deteriorate and appears to become more vulnerable to certain chronic illnesses and diseases.’ (Kenneth H Cooper, M.D., M.P.H. 1968) 2

This article marks the beginning of a new series for the mature aged distance runner. My previous two series about training principles and practical philosophy have discussed many topics that relate to the competitive among us. While I have covered a range of information within these series, there have been some gaps in the examination of biological and other factors that are critical to high performance.

The Fundamentally Speaking series is an attempt to fill those gaps, and explore the still developing science and perspectives about distance running and aging. In getting back to basics, I may cover old ground, walking some well-trodden paths. But hopefully, the target audience will gain some new insights, or at least jump off points for reflection about their own situation, light bulb moments to understand why it is the way it is for them. And convert such reflection into action.

-

Chosen Topics

The topics I have chosen to examine are:

Aerobic threshold;

Anaerobic threshold;

Effect of endurance activity on the heart;

Body composition and weight;

Changes in hormones;

Sleep;

Nutrition;

Arthritis; and

Shoes.

To understand what we are dealing with, over the course of this series, a number of lenses will be applied – aging, non-athletic, endurance, medical and theoretical. Like many readers I am a mature competitive runner who has suffered various incapacities. So, as you would expect, I am concerned about the identification of any deterioration in physical capacity due to aging, as a consequence of natural biological changes, as opposed to a deterioration caused purely by the extent of endurance activity and/or the use of inappropriate training methods.

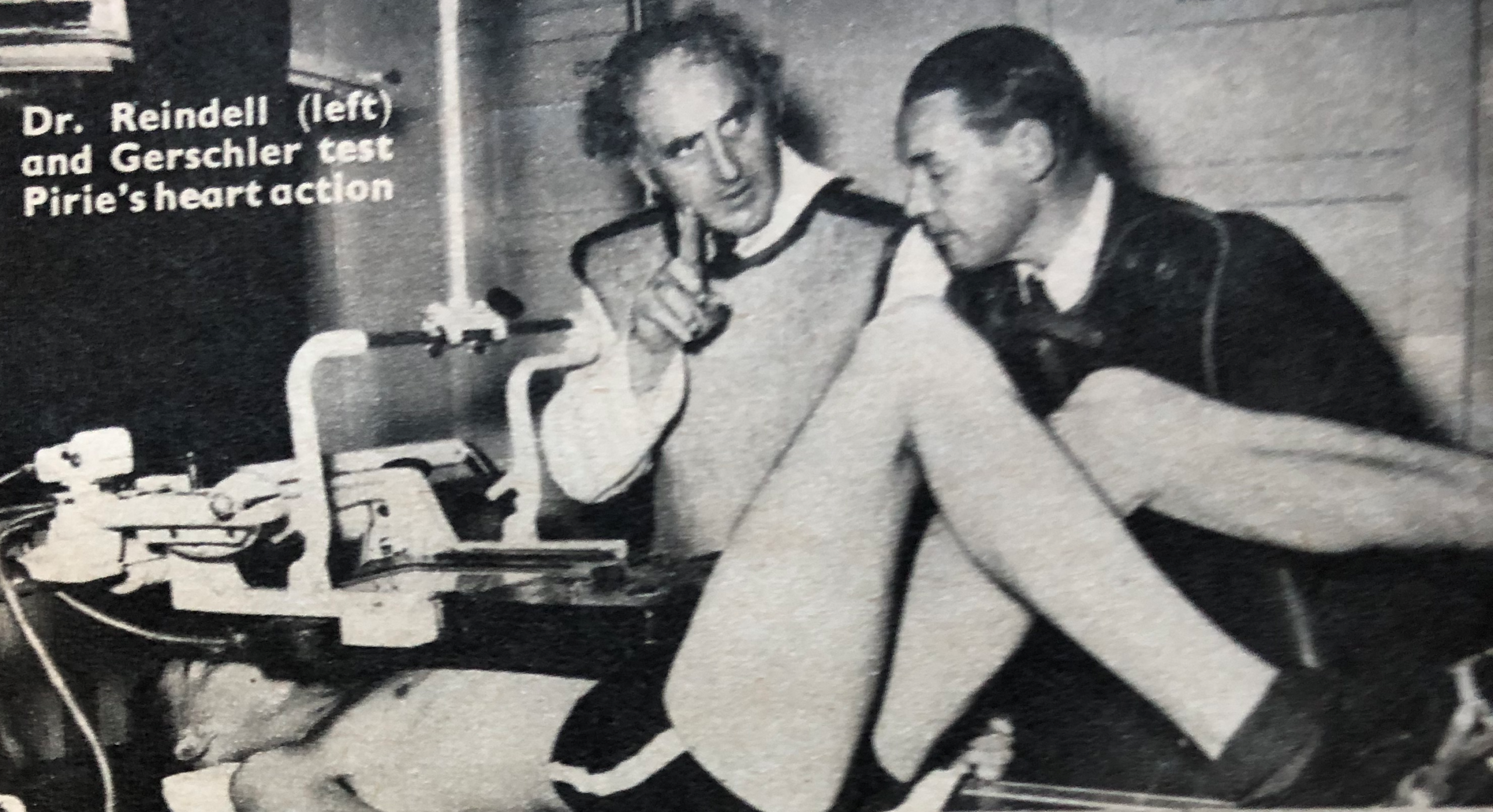

Mainstream literature on the chosen topics is supported by the research of exercise scientists and physiologists, coaches, medical academics and health professionals. There are a multitude of publications steeped in the science of exercise physiology that stretch back to the era of Dr. Woldemar Gerschler and cardiologist Dr. Herbert Reindell, the fathers of interval training. More recently, a body of evidence has started to develop about the implications of endurance exercise for an aging athlete, particularly its effect on the cardiac system.

Although much of the research is limited by an inherent male bias, in this series I will attempt to differentiate between the effects on men and women.

-

Why these topics?

I have chosen these nine topics, not only because I can write about them based on personal experience, but also because I view them as fundamental to the achievement of high-performance levels.

‘Shoes’ is an outlier, in the sense that it is a product of technological endeavour, that responds to and can influence a distance runners biomechanics. Appropriate choice of footwear can be an enabler of higher levels of performance. But clearly, of itself it does not fall nicely within the category of topics to be covered.

You could argue that arthritis is a natural consequence of living longer, afflicting non-runners and runners. It is such a common condition in the aging cohort that I consider it demands close attention. For the distance runner the onset of arthritis, particularly osteoarthritis, can be debilitating. For most it requires a level of adaptation in training, and a tailored management of exercise regimes, to continue racing. In extreme situations it is the crossroads for a lifetime decision about whether to continue running at all.

2.1 Where to from here?

As a basis for future articles, it is useful to provide a simple explanation of some of the topics, and what the discussion will likely turn on for a mature competitive distance runner.

There is a raft of information available about the two key thresholds of endurance activity, aerobic and anaerobic. They are the yin and yang of any reputable analysis of exercise physiology, and will be covered as one broad ranging topic. It will lead to an extended discussion about VO2 max, maximal heart rate, mitochondria, physiological adaptation, a recommended mix of quality and volume, and training zones. The advent of terms used in scientific and academic research circles such as high intensity interval training (HIIT), high intensity training (HIT), and metabolic equivalent of tasks (MET) can confuse a layperson such as myself. But I will do my best to unravel their meanings.

Critically, an aging lens will be applied with gusto, to truly understand the implications of all things ‘lactic’, and not forgetting the real physiological culprit of hydrogen ions.

Following on from the threshold discussion I will attempt to cover the effect of endurance activity on the heart. I expect that this will be the most controversial of all topics covered, though ‘shoes’ always gets a strong reaction. I regularly hear from peers about cardiac conditions that have arisen for runners in their later years that may have resulted from excessive endurance activity. The main dangers appear to be increases in coronary artery calcification (CAC) and the development of atrial fibrillation (AF). However, it is important to maintain perspective, a balanced outlook, in weighing up the pros and cons of exercise for a mature endurance athlete and come to a common sense understanding of optimal training to minimise any risk of cardiac complications. Certainly, for the vast majority of endurance athletes there is no doubt that regular exercise increases lifespan by improving heart health.

Many studies in this field tend to focus on the mature endurance athlete as a homogenous group across all sports disciplines, coalescing the experience of individuals across multiple disciplines such as running, cycling, swimming and skiing etc. I note that to enable fair comparisons across disciplines, volume and intensity is sometimes measured in research studies by METs.

Body composition and weight – front and centre to this topic is body fat and where that sits. It is often said that if we are lighter, we should be able to run faster. But for an aging athlete it’s a complex equation. I will test the assertion of lighter = faster by a deep dive into all things body composition

We all experience natural changes in hormones as we age, though there are differences between men and women. What are the significant hormonal changes and how do they affect performance as men and women age?

Sleep is underestimated as a recovery strategy and underdone by many who have competing life priorities. Whilst it is difficult to define, there is no doubt that adequate sleep (hours) of high quality (no interruptions) is important for the effective training recovery of a distance runner. I’ll examine the cycle and phases of sleep in detail to pull back the doona on this important factor in an aging athlete’s performance.

Nutrition is the process of utilising food for growth, metabolism and repair of tissues. 3 As arguably one of the two most significant contributors to adequate recovery (the other being sleep) 4, how can we build effective nutritional strategies into our lifestyle?

Osteo and rheumatoid arthritis are the two most common types of arthritis, the former largely associated with wear and tear of joints and the latter an inflammatory disease of joint linings, where the body’s immune system is attacking the body’s own tissues. 5 I will explore whether strategies exist to reduce the onset of arthritis, and mitigate its effect, to continue training and competing on some basis.

Shoes are the running world’s silver bullet, endlessly redesigned, remarketed, and re-hyped. How much benefit does a mature runner really gain from the use of a carbon plated shoe? ‘Cheat shoes’, as they have become known in some quarters, may present particular challenges relating to gait, biomechanics and leg and ankle power and thrust. I’ll examine the pros and cons.

-

Concluding Comments

I know that many mature aged distance runners are well informed on these topics, particularly in relation to general principles, and some of the obvious discussion threads that permeate our running lives. However, I’ll attempt to introduce arguments and research that may not be widely known to the readership, to better inform the mature aged competitor to answer the age-old question: What can I do to keep going?

References:

1.Gerschler, W, article titled The Man Behind the Champion, World Sports magazine, September 1954, pp28-31

2.Cooper, K, Aerobics,1968, p13

3.Zohoori, F, Chapter 1: Nutrition and Diet, monographs in oral science, National Library of Medicine, USA, 2020, available here.

4.Friel, J, Fast after 50, 2015, p203

5.Arthritis Overview, John Hopkins Medicine, 2024, available here.