‘The less we interfere with the natural movements of our feet, the better we are going to perform, so shoes have to be avoided which promise to cushion and control what fits inside them in accordance with what the designers think should happen.’ (Arthur Lydiard, 2000)1

‘It is important to recognise shoe-induced changes in one’s running, understand their implications (positive or negative), and continue to study whether one might benefit by attempting to adopt a more barefoot-style stride while running in shoes.’ (Peter Larson & Bill Katovsky, 2012).

In this article I take a break from past content in the Fundamentally Speaking series that has centred primarily on physiology. Against my better judgement, for I know this is a hot topic, I examine the issue of running shoes.

At the time of finalising this article, I note that World Athletics has launched a request for proposal (RFP) for athletic shoe regulations, involving a comprehensive review of the current process for approving athletic shoes for competition, and non-compliance thereof.

Content is narrow in construct, rudimentary at best, zeroing in on those issues that are significant to the mature runner.

- Introduction

I do not profess to be an expert in this field, and I admit to an inherent bias when it comes to shoes, having experienced all manner of footwear from the early Onitsuka Tigers (later to become ASICs) as a 12 years old kid, to the carbon fibre plated (carbon) ‘cheat’ shoes of today (‘super’ shoes if you want to be kind) as a mid-sixties masters’ distance runner.

I have firsthand experience of poor shoe choice, so maybe I can speak with some practical authority, even though not scientifically based. In my first distance running career, those injuries that I can confidently say were related to poor shoe choice were recurrent metatarsal strain, chronic Achilles tendonitis, and a one-off stress fracture of the tibia – all in my twenties. In my second career I suffered recurrent Achilles tendonitis, metatarsalgia, a reoccurrence of the exact same stress fracture of the tibia of my youth, and a minor skirmish with plantar fasciitis. All but the metatarsalgia (currently dormant but I continue to manage), were totally resolved during my fifties, by more appropriate shoe choice and foot management advice from allied health professionals.

The shoe companies would have you believe that there is science in their product development – and I am sure there is some – as they pump out the most recent versions of their top of the range product to the masses. However, there is so much written about shoes that it can be difficult for a mature age runner to decide what’s best. Shoe companies tend to target information to the younger set, where the market is larger.

It has been stated by authoritative sources that there is no ideal biomechanical running action, just as there is no such thing as the ideal shoe, only a shoe that best suits an individuals’ specific biomechanics. I don’t think I’m alone in my opinion that the most recent shoe version, or the most expensive, aren’t always the best: the hype rarely matching the reality. I am one of those runners, who once I find the ‘ideal shoe for myself’, I will stick with it until it goes out of production, come hell or high water, only embarking on risky experimentation when I have to seek a new shoe. I am not attracted by the glossy ads that shout out loud to confused potential buyers. I have no long-term brand loyalty. My only loyalty is to myself, in making sure that I obtain the best shoes for me. It’s always a point in time decision.

There are many different aspects to choice of shoes, not the least being the age of the buyer. In this regard issues of biomechanics, power, propulsion, feet, running economy and comfort, come into sharper focus. While it is my view that a direct causal relationship exists between injury and shoe choice, the promotion of shoes tends to focus on perceived performance advantage and emphasises injury prevention, sometimes erroneously. Understandably, this is the default position in the marketing game, where profits are at stake. Of course, the romanticised account of barefoot running in Christopher McDougall’s Born to Run (2009) further complicates matters.

At the other end of the spectrum, a Runner’s World article published on 4 June 2025 by Scott Douglas3 provides a lengthy explanation about super shoes, highlighting that the fibre plate alone does not result in improved performance. Douglas also points to the lightweight super foam in the midsole that boosts efficiency by providing a better energy return, thereby improving running economy.

- A Personal Experience

I resisted the carbon shoes for many years. However, the temptation became too much for me in late 2023, when some running mates told me that I could improve my 5000 metres time by up to 30 seconds if I made the switch. At 64 years of age, racing well, and still harbouring ambitions of running sub-19, I bought a pair of the carbon plated ‘monsters.’ In making this decision I stupidly had no regard to the ingrained changes to my biomechanics that had occurred with age and injury (notably I can no longer straighten either of my legs, my left knee being worse than my right).

The stiff plate and high stack (cushioning) affected my gait and foot strike, causing a change in force impacting my knees. My leg action felt clunky. The end result, after only two wears (6k jog and 4k track race) of the ‘super’ shoes, I was out with injury for one year. The shoes had aggravated my osteo-arthritic left knee condition, something I have to carefully manage in balancing training volume and intensity. It took many weeks absence from running, and three resets, before I could recommence any semblance of a reasonable training program. Later, as one local shoe representative said to me, older runners typically have less strength and flexibility in the ankles that can affect the push off action, meaning they ‘can’t get over the top of the carbon plates.’

I paid a high price for a failure in my due diligence, oblivious to doubts about the benefit of carbon fibre shoes for slower, and older, runners. Although I consistently race at a national standard for my age, in absolute terms, I have to accept that I am slow. The carbon design is for mid foot strikers at the elite level (who tend to exhibit ‘good’ running form), the effect on running economy and improved racing performance for the ‘slower average runner’ being variable, depending on the biomechanics of the individual. High responders typically get more benefit, achieving faster comparative speeds or velocity, whereas others may receive marginal or no benefit whatsoever. Combined with their lack of stability caution is demanded in transitioning to more frequent use of the carbons.4

For the mature distance runner to derive a maximum performance benefit from carbon shoes, this will be contingent upon the retention of strength and power of leg muscles and ankles, and the elasticity of tendons: or put another way, the mitigation of a range of age-related decline that affects propulsion. If your legs and feet aren’t up to it, you could have problems. If you are prepared to gradually transition to carbon shoes, maybe it can work for you, but this is not without risk. The change in force and torque (rotary force) has to go somewhere! And as some studies have found, there may be a link between carbon shoes and bone stress injuries of the feet.5 Ultimately, you may find, as I did, that your biomechanics are an inhibiting factor, and you are unable to take full advantage of the design of the shoe, and there is greater potential for injury.

- A Philosophical Tirade

So, I have sworn off the carbon fibre plates for racing and training. And although they may be consigned to the dustbin of distance running history by our current generation of up and comers, I prefer the traditional flatter soled, lower stacked shoes, with minimal heel drop. I know that a big drawcard for the super shoes is their ‘positive’ impact on racing performance. But having tried them, and I acknowledge the reader may view me as a hypocrite, I cannot countenance the improvements resulting from technological advancement as credible, or inherently superior to the performances of champions of the past. In hindsight, I’m glad I didn’t make a successful transition to the cheat shoes, because if I ended up running a lot ‘faster’, all I’d be doing is fooling myself when I really hadn’t made any improvement based on my own steam.

Call me a luddite if you like, but there has to be limits to technological advancements that discount the intrinsic value of the human performance achievements of the runners of yesteryear compared to today’s runners. My line in the sand is the current day cheat shoes. Noone will convince me that the best marathon times of Deek and Monas, or Lisa Martin, are innately inferior to the ‘faster’ times achieved by today’s distance runners. Or that today’s elite runners train harder than the champions of the 1970s to 1990s.

Critics of my stance will say what about the advancements in shoe development from the very early days up until the advent of carbon fibre plates? Would you discount the performances of Deek et al when compared to the pedestrians of the early 20th century, just because they wore better designed shoes? Well, I say that the elite runners of Deek’s era could still feel the ground beneath their feet. There was a reasonable sensory relationship between shoe, foot and ground. The super shoes dull that sensory experience, and assist the distance runner in a super-charged artificial way, with more reliance on technologically-enhanced propulsion, at the expense of basic human movement that is driven by innate muscular strength, power and flexibility.

Forgive my tirade, for I have rambled. But before we discussed particular issues relating to the mature runner, I had to get this issue off my chest.

- Some Basics

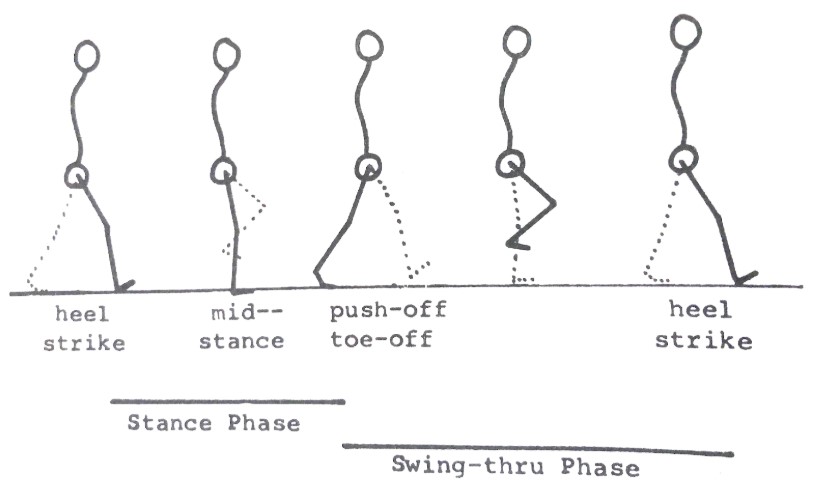

The act of running involves the movement and changes in position of muscles, joints, and other parts of the body such as feet, legs, pelvic area (core), and torso. Hips, knees and ankles are flexed and extended during running. In simple terms, when running ‘about 85 to 95 times per minute, each leg passes through a stance phase, during which the foot is in contact with the ground, and a swing phase, during which the foot is free from the ground and the leg swings forward from the hip preparing for subsequent foot strike and initiation of another stance period.’6 Pronation (inward rolling of the foot) or supination (outward rolling) may occur during the stance phase of gait. A gait cycle begins when a foot strikes the ground, continues through stance, progresses through swing, and ends when the foot hits the ground again.

Given the number of parts involved, the repetitive nature of running and the high foot to ground impact, there is a real risk of injury should biomechanics of the individual change because of a poor choice of running shoe, or if the existing biomechanics are not a good match for the chosen shoe. Everything can be thrown out of kilter. Therefore, shoes are critical. And having said that, everything starts with the feet.

4.1 Feet: What are They Good For?

Your feet are essential for propulsion. A simple enough statement that cannot be contested. Granted you need muscular strength in the legs, a good range of motion in the knees and hips, adequate flexibility of the ankle to propel you forward, and strong calves and Achilles tendons to manage the rebound, but if your feet are not fit for purpose, you are going nowhere fast.

For masters runners there are some extra considerations to be had. Major changes to your feet resulting from ageing, whether runner or non-runner, are their widening and lengthening, a loss of padding under-foot that affects power, stiffness that affects mobility in foot and ankle, and a flattening of the foot caused by mild settling of the arches. ‘The most common foot complaints by older adults are toenail and skin problems, calluses or corns, swelling, bunions and arthritis.’7 So, the mature runner has a lot to contend with.

4.2 Pronation

Pronation is simply the natural way your foot hits the ground. Specifically, it is the ‘inward roll of your foot as it lands to help absorb shock and distribute weight’8, and is personal to the individual.

From my reading of all the literature, neutral pronation is the gold standard in foot fall or foot strike. If you are naturally blessed with this attribute, it will save you time and money agonising over what orthotics to buy, or whether to ride it out and accept that this is just the way things are for you.

Much is made of overpronation and supination leading to injuries. Overpronation is the foot rolling too far inward after landing and supination is where the foot doesn’t roll inward enough, the outer edge of the foot absorbing most of the impact.9

Overpronation can lead to flattened arches, and those suffering this ‘affliction’ are often advised to wear motion-controlled shoes and/or orthotics. Supinators are typically advised to seek flexible and cushioned shoes.10

In my experience, some advertising pushes a runner towards orthopaedic products that are not required. If, as an overpronator, you are pain free, the use of orthotics as a ‘corrective’ motion control product to improve your gait is a dubious strategy in many instances. I have used orthotics intermittently during both of my running careers to alleviate metatarsal pain and oncoming plantar fasciitis, but not to address issues of pronation, for l am one of those lucky runners who are neutral. In my view, less reliance on artificial support as a permanent fix and more emphasis on the strengthening of identified areas of weakness is the way to go, if at all possible.

- Barefoot Running

You cannot write an article about shoes without addressing the barefoot dilemma. Proponents of barefoot running or minimalist shoes claim injury prevention, enhanced running efficiency, and improved performance compared with standard running shoes of the pre-carbon plated era. Within these arguments is an underlying assumption that shoes can mask weaknesses in your feet and lower legs.

However, during 201311 an extensive review of articles that examined barefoot running against use of running shoes stated that ‘moderate evidence supports the following biomechanical differences when running barefoot versus in shoes: overall less maximum vertical ground reaction forces, less extension moment and power absorption at the knee, less foot and ankle dorsiflexion at ground contact, less ground contact time, shorter stride length, increased stride frequency, and increased knee flexion at ground contact.’ The author’s summation was that ‘Because of lack of high-quality evidence, no definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding specific risks or benefits to running barefoot, shod, or in minimalist shoes.’

I like running barefoot occasionally for short distances (usually a recovery run after a hard race) on manicured football pitches because it does give a feeling of release for my feet – and I get around barefoot a lot in my everyday life. Running barefoot for short periods on an irregular basis may strengthen your feet and improve proprioception. Though it does depend on the individual, as there are just as many reports of complications for mature distance runners that are caused by barefoot running. I wouldn’t recommend barefoot running as a standard approach to regular training. It’s on the other end of the spectrum to the carbons. I reckon that somewhere in the middle of this spectrum is, in most cases, optimal for mature runners.

I have always tended towards shoes with lesser cushioning and a small heel drop, if any. In my twenties this was likely the cause of repetitive metatarsal strains during high mileage periods, largely on the roads. However, I think there is value in shoes with minimal cushioning if your biomechanics allow it, you vary the terrain wisely and your feet are strong enough to take it.

The benefits of a low heel drop can include the potential to improve cadence, promotion of forefoot and midfoot strike, and some possible assistance with ITB, anterior knee pain, and gluteal overuse syndrome. But a word of caution: low heel-drop shoes enable greater ankle flexion during landing and can put extra stress on the foot, ankle, Achilles and lower leg.12 Well known sports podiatrist Clifton Bradeley has ‘observed a higher prevalence of overuse injuries and tissue stress in runners who consistently use minimalist shoes or those with a negative heel-drop.’13

However, I successfully used thin soled, no heel drop, dirt cheap shoes, to assist my recovery from some nagging ITB issues during my fifties, so I can attest to their effectiveness in this regard. But then again, they also suited my biomechanics at that time and were a good fit for the terrain I was running on – a lot of dirt tracks and grass. Transitioning to a minimalist shoe requires patience, and some practical planning. For instance, you may be asking for trouble if you immediately start wearing shoes with a zero drop and no cushioning to speak of. Best to take it one step at a time. Integrate such shoes gradually and try shoes with differing combinations of cushioning and heel drops, on varied terrains, as part of your shoe rotation. I accept that this may be expensive, but it will be worth it in the end.

One aspect that can be overlooked is what you wear as part of your everyday life. The wearing of inappropriate general footwear for long periods of time can undermine the strengthening effects of chosen running shoes. For instance, Achilles issues can be unknowingly aggravated by the constant toing and froing between higher heeled general footwear and lower heeled running shoes. That’s why I finally settled on flat soled business shoes, in my late fifties, during my last years of employment.

- Open the Gait?

It is evident that a lack of muscular strength in the leg (particularly calves) and inadequate ankle flexibility and elasticity of the Achilles tendon, are major contributors to poor balance and proprioception, and reductions in stride length and cadence.

In a range of YouTube videos, Peter Attia has said the reason for falls for those aged over 65 in the general population is a lack of power in the foot, poor toe strength, lower limb weakness and an inability to adjust/adapt quickly (react) in response to what causes the fall. It’s not necessarily a lack of balance per se. Certainly, I have come a cropper on a couple of occasions recently, despite working on my own deficiencies (maybe not enough), suffering falls through tripping and not lifting my feet – and I know I am not alone.

While this may be getting off topic, I suggest that combined with necessary strengthening, stretching and flexibility strategies, Attia’s comments underscore the value of a mature runner persisting with minimalist athletic footwear, as much as practicable, on varied terrain, to retain a degree of sensory awareness and enhance proprioception.

With increasing age, cadence and stride length tend to decrease, affecting a runner’s gait. Over time, this can result in changes to biomechanics, including foot strike. Cadence is the number of foot strikes per minute and stride length is the distance covered with each step.14 Generally, it appears that the quicker your running cadence and/or the shorter your stride length there is less risk of bone stress injury (aka stress fractures), because in overall terms you are in less contact with the ground. The slower your cadence and the longer your stride length there is a greater risk of injury, because the ground reaction force (GRF) is greater.

Basically, if your cadence is quicker, although you touch the ground more frequently, your foot strike is lighter and you hit the ground for a shorter period of time. I like to think of it as flicking along, rather than pounding down. So, as we get older, based purely on a decrease in cadence, if nothing else, there is the likelihood of developing into a pounder.

6.1 Body weight also comes into play. A heavy runner exerts more force on the ground and receives a greater force in return than a lighter runner, so this will obviously influence shoe choice. Typically, a heavier runner will experience greater tendon forces and require shoes with cushioning. For this type of runner minimalist shoes can be problematic, needing careful management.

With increased age some of us will definitely carry more weight. It may not be in the same ratio of muscle to fat as in our youth, and it’s likely that our mass will have increased and our body composition changed, meaning our shoe choice may need to change. Personally, I have noticed a better tolerance for lighter, more minimalist shoes in my fifties, whereas in my sixties, though not wanting to go overboard on the cushioning, I have definitely transitioned to shoes with some additional padding.

- Conclusion

It seems that the elite open level is where the mechanics of the carbons really come into play. Benefits for the mature runner, even the elite masters, are less evident as we progress through each decade, and the ageing process takes hold.

In real terms we are slower, our biomechanics and body composition have changed, affecting all those essential ‘parts’ that assist to propel us forward. Our feet are more firmly planted on the ground as we engage in our attempts to run. The extent to which we can mitigate the ageing process will influence our choice of the optimal running shoe, whether carbon, minimalist, or even unshod, on some basis – though I am less enamoured of the carbon monsters.

I deem the carbons to be a risky proposition for the mature runner as they can either change your biomechanics, or not be a good fit to your existing biomechanics, in both instances increasing the potential for injury. They were not the answer for me. They were a performance decimator. However, I accept that I am biased by my own personal experience and they could be the answer for some of you who want to embrace the new world order of high-tech sports assistance – a performance liberator.

I finish this article with a quote from the master, Arthur Lydiard, who stated that ‘when you are looking for shoes to run in, try everything available for lightness, for easy bend, upwards and downwards, at the arch in the middle of the shoe, for uncluttered uppers and the least number of stabilisers, counters and inserts.’15

While I concur with Lydiard’s advice as one of aspiration, for the ageing runner into their sixties and beyond, changes in the feet demands some consideration of additional support and cushioning. For the last thing you’d want, is to incur an overuse injury or soft tissue damage. But, yes, keep the cushioning to a minimum, if at all possible.

And stay light on your feet.

Sources

1 Lydiard, A & Gilmour, G, Distance Running for Masters, 2000, p55

2 Larson, P & Katovsky, B, Tread Lightly – Form, Footwear and the Quest for Injury-Free Running, 2012, pp237-238

3 Douglas, S, The Secret Behind Super Shoe Speed? It’s Not Just The Carbon-Fiber Plate – A deep dive into the golden age of super foams, Runners World, 4 June 2025 – https://www.runnersworld.com/gear/a64969945/secret-to-super-shoes/?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=likeshop&utm_content=app.dashsocial.com/runnersworldmag/library/media/538222646

4 Reilly, J, Will Carbon Shoes Make Me Run Faster? tritrainingharder.com, 4 November 2022 – https://tritrainingharder.com/blog/2022/06/will-carbon-shoes-make-me-run-faster

5 Tenforde, A, Hoenig, T, Saxena, A & Hollander, K, Bone Stress Injuries in Runners Using Carbon Fiber Plate Footwear, Springer Nature Link, 13 February 2023 – https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-023-01818-z

6 Anderson, O, Running Science, quote and summary information from p29, 2013

7 Vonhof, J, Fixing Your Feet, sixth ed, 2016, pp25-26

8 The Running Week, 23 March 2025

9 The Running Week, 23 March 2025

10 MacPherson, R, How Running in the Wrong Shoes Can Impact You, VeryWell, 25 September 2024 – https://apple.news/A-YEdM61KSlufZQEAOSNAQw

11 Perkins, K, Hanney, W, & Rothschild, C, The Risks and Benefits of Running Barefoot or in Minimalist Shoes – A Systematic Review, Sports Health – A Multidisciplinary Approach, Sage Journals, November 2014 – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4212355/

12 Subic, J, Heel to Toe Drop: The Ultimate Guide, RunRepeat, 7 March 2024 – https://runrepeat.com/guides/heel-to-toe-drop

13 Bradeley, C, cited from an extensive post in Steve Magness Science of Running facebook account, 7 December 2024

14 Howley, E, Worried About Stress Fractures? Look at Your Cadence, run.outsideonline.com, 10 June 2025

15 Lydiard, A & Gilmour, G, 2000, p57

Other Sources

Douglas, S, Will Super Shoes Permanently Change Your Running Form? Runners World, 1 April 2025

Magness, S, How to Run: Running with proper biomechanics, scienceofrunning.com (an abridged excerpt from the book Science of Running), 2010: https://www.scienceofrunning.com/2010/08/how-to-run-running-with-proper.html?v=47e5dceea252

Subotnick, S, The Running Foot Doctor, 1977