Part 1: The Build-Up

The Men’s Olympic Marathon of 1984 was one of the greatest marathons in Olympic history. It was a deep field and a highly competitive race held in tough conditions (25 degrees, 80% humidity) and in a city which experienced high levels of pollution. The conditions were a major concern for many athletes and coaches in the build up before the Games.

The marathon was the final event on the program and fans out on the course and watching via satellite would see a riveting drama unfold, where a number of favourites would falter, a legendary veteran of the sport would achieve his highest career honour and two newcomers to the event would also make their way onto the podium.

The Main Players:

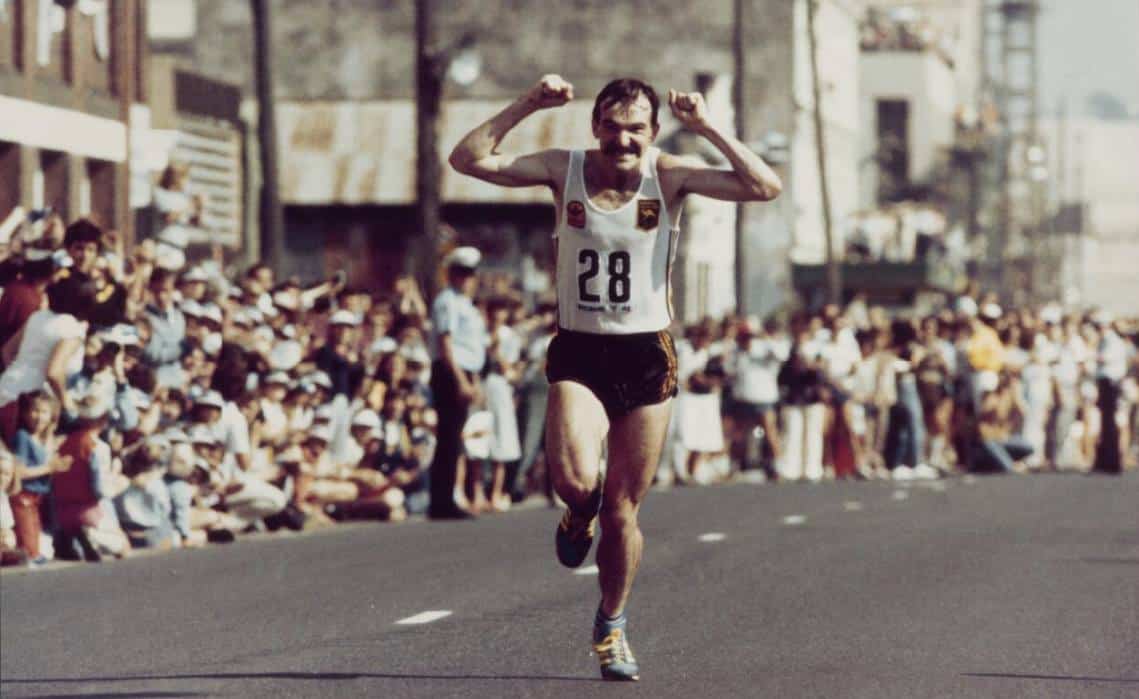

Robert de Castella (AUS):

Robert de Castella was a 27 year-old biophysicist from the Australian Institute of Sport who was the biggest favourite going into the race. He had enjoyed an unbeaten run of four consecutive victories in major marathons, beginning with his world record (2.08.18) in Fukuoka in 1981. The record, which was a 16 second improvement on countryman Derek Clayton’s 2.08.34 from 1969, was not recognised as a world record at the time, as Alberto Salazar’s 2.08.13 – in New York a month or so earlier – was considered the best on record.

De Castella won the Commonwealth title in Brisbane in 1982 with a captivating come-from-behind victory over Juma Ikangaa (TAN). That win had established de Castella as a national hero and his astonishing performance in Queensland’s capital on a warm, humid spring morning helped launch a nationwide running boom. In 1983, he outkicked Carlos Lopes (POR) in the big match race against Salazar in Rotterdam (2.08.37) and de Castella then won the inaugural world marathon title in Helsinki (2.10.03) with a dominant display over the final 6km. ‘Deek’ (as he is known) had the best year of his career in 1983. He had also finished 6th in the World Cross Country Championships in Gateshead, won the prestigious Cinque Mulini cross country in Italy – by a huge margin – and he ended the year with a second place finish and a 10 second PB in the Zatopek 10,000m in December (28.02.73).

De Castella came into the Olympic year maintaining his high volume of training (200km + per week) and planned a racing/training tour of the US in March/April ’84. By the time Deek got to Phoenix, he was rising. He ran superbly in the Continental Homes 10km road race, finishing second in a super fast 27.48. Though he was only 21st in the World Cross Country Championships in New Jersey a few weeks later, he and coach Pat Clohessy still felt he was on course for gold in LA.

Months out from the Games, Deek experienced some injury niggles which, by his own admission, may have been the result of overtraining. Deek was perhaps not quite in the form that took him to victory in Helsinki and there was huge pressure on Deek in Australia as one of the nation’s most high-profile gold medal favourites for LA. De Castella was 180cm and 72kg, with the legs of an AFL full forward, and so was unusually large for a marathoner. He cut an imposing, intimidating figure out on the roads, tracks and cross country courses around the world. Though he was perhaps off his game a little, with his experience, courage under fire and superhuman ability to focus and to push his body to the limit, he would be feared by the world’s best. All eyes were on Deek.

Carlos Lopes (POR):

At the age of 37, Lopes was in career-best form. The diminutive veteran from Lisbon, who had won Olympic silver (10,000m) and a World Cross Country title in 1976, had experienced a career renaissance in the previous two years, after several injury setbacks in the late ’70s and early ’80s

Since his 35th birthday in 1982, he had run personal bests from 1500m to the marathon, won World Cross Country medals (silver 1983, gold in 1984) and had moved to the marathon.

Lopes dropped out of the New York Marathon in 1982, but had pushed Deek all the way to the line in Rotterdam ’83 to finish second (2.08.39).

Prior to the Games in 1984, Lopes was running brilliantly. In March, he had a commanding victory in the World Cross Country Championships, surging away from Tim Hutchings (ENG), Steve Jones (WAL) and Pat Porter (USA) in the last 1200m.

He led Sporting CP clubmate Fernando Mamede for much of the race in Stockholm in July, when Mamede smashed the world 10,000m record (27.13.81). Lopes was second, moving to second on the all time list (27.17.48).

Lopes had a major scare 10 days before the marathon. Just prior to flying to the US, he was hit by a car whilst out training. He was a little bruised and was sore for a few days, but recovered well. In the form he was in, Lopes would be dangerous with any pace or in any conditions.

Alberto Salazar (USA):

Cuban-born American Salazar , as mentioned, held the world record for the marathon (2.08.13), though he would lose this record when the New York course – on which the record was run – was remeasured and found to be 150m short.

Salazar was an outstanding performer at the college level for Oregon University and, upon graduation, he had distinguished himself at home and internationally on the track, roads and over cross country and by 1982 he was among the world’s best distance runners from 5000m to the marathon.

The 26 year-old had won the 1980 New York Marathon on debut in 2.09.41 – then the fastest debut ever – and since then, he continued to improve. He ran his later disallowed ‘world record’ in the NYC marathon the following year and in 1982, he ran American records in the 5000m and 10,000m, won a silver in the World Cross Country Championships in Rome and ran a Boston Marathon record when he won the famous ‘Duel in the Sun’, beating Dick Beardsley. In unusually hot conditions for April, the two men fought it out all the way, with Salazar just edging the gutsy Minnesotan (2.08.51 to 2.08.53). He also won his third consecutive NYC Marathon that year.

Salazar was second in the World Cross Country in 1983, though from then on, he experienced a worrying slump in form. He failed to go with Deek’s surge 7km from the finish in Rotterdam and finished 5th, a minute-and-a-half behind Deek and Lopes. He was last in the World Championship 10,000m final and was left behind by Toshihiko Seko’s kick in the late stages of the Fukuoka Marathon and again finished 5th (2.09.21).

The US Olympic Trial for the marathon was held just 11 weeks out from the Games marathon, a limited time to recover from a major race. Salazar finished second behind Pete Pfitzinger, though given Salazar’s renowned toughness and determination, he was still very much in the mix. Salazar was renowned for his capacity to rise to any challenge. He had been close to death after a road race in the US as a 20 year old and his Boston Marathon exertions led him to another hospital trip after he was dangerously dehydrated after the race. He was still many pundits’ favourite – especially in the US.

Toshihiko Seko and the So twins (Takeshi and Shigeru):

The three Japanese entrants were among the favourites, particularly 28 year-old star Toshihiko Seko. Seko had been a leading international star in the marathon since his three wins at Fukuoka (1978, ’79 & ’80). He was second in Boston in 1979 behind Bill Rodgers’ record-breaking run, but got his revenge two years later, beating Craig Virgin and Rodgers in a course record (2.09.26). That year he had also smashed the world track records for the 25,000m & 30,000m in New Zealand.

Seko was coached by Kiyoshi Nakamura who was a strict disciplinarian who subjected his athletes to a rigorous training regime and insisted that an athlete’s commitment was total. This approach suited someone of Seko’s character, though it did lead to Seko sometimes overdoing it in training, leading to injury problems which plagued him in 1982. Seko stormed back to the elite level in early 1983, with a win at Tokyo in a PB of 2.08.38. His win at Fukuoka (2.08.52), outkicking an elite field, was equally as impressive. Having missed the Olympics in Moscow 1980 (Japan boycotted the event), Seko was absolutely fixated on winning gold in LA.

Shigeru So had run at Montreal 1976, though finished in 20th. He had a major breakthrough at the Beppu-Oita Marathon in 1978, running the then second fastest of all time (2.09.06). He had been a consistent performer in marathons since then, though had only won in Japan. His 2.09.11 for third in Fukuoka eight months earlier indicated he was in top form.

Shigeru’s brother Takeshi had been similarly consistent over the previous 5 years or so, running his first sub 2.10 (2.09.49) behind Seko in Fukuoka in 1980, in the fiercely competitive 1980 race (which also featured a fourth place finish by Aussie Gary Henry in 2.10.09, with Deek 8th in 2.10.44). Takeshi had been in great form the previous year, with a PB of 2.08.55 behind Seko in Tokyo and a 2.09.17 in Fukuoka for 4th.

Seko, along with the 31 year-old So twins, would be on the radar of most experts once the gun went off in LA.

John Treacy (IRL):

The 27 year old Treacy was taking a huge gamble in entering the marathon. So were national team selectors, who had faith in Treacy. Though Treacy had never run a marathon, he had done the nation proud whenever he donned the green singlet of Ireland. After a few years battling with injuries, he had built a solid foundation of conditioning and had begun to return to the type of form that had led to consecutive World Cross-Country titles in 1978 and ’79 – most notably the 1979 win at a packed Limerick Racecourse, providing one of the iconic moments in Irish sporting history.

He had collapsed in the heats of the 1980 Moscow Olympic 10,000m, but had recovered sufficiently to finish a creditable 7th in an ultra competitive 5000m final.

In the years between Moscow and LA, he suffered various injuries. He had failed to make the final of the 1983 World Championships 10,000m and looked a shadow of his former self. However, he had completed a solid block of training over the winter of ’83/’84, increasing his mileage with a view to competing in the marathon in LA. Things were coming together slowly.

There were some encouraging signs in the months leading up to the Games. He had finished 13th in the World Cross Country Championships in New Jersey, his best result in years and he ran a superb 5000m in Oslo in June. He broke World Champion Eamonn Coghlan’s Irish record and ran 13.16.81 – several seconds faster than his best.

Treacy ran the 10,000m final a week before the marathon and though he led briefly at around halfway, he was unable to live with the brutal surges of Nick Rose (GBR) and the later disqualified silver medallist Martti Vainio (FIN). Italian Alberto Cova won and completed a ‘triple crown ‘ of European, World and Olympic titles. Treacy’s ninth place finish (28.28.68) turned out to be the ideal tune up for the marathon. Los Angeles was a long way from Tipperary for the rail thin athlete with the awkward yet effective running form. Accustomed as he was to the rainy days at home and the brutal winters of North Eastern USA while at college in Providence, Rhode Island, Treacy would find running his debut marathon in the heat and humidity of California an enormous challenge.

He would be joined by another Irishman and Rhode Island scholar , Jerry Kiernan. Keirnan, inspired by his celebrated compatriot Treacy, would also rise to the big occasion.

The British:

Though most of the attention from British athletics media and fans at these Games was focused on the middle distance trio of Seb Coe, Steve Ovett and Steve Cram, the British distance running teams – men and women – were very deep in terms of talent and medal prospects and the three British men in the marathon were all accomplished athletes and outside medal chances.

Geoff Smith, the Boston Marathon champion, had run his PB in New York (2.09.08) the previous year, when he had set off at an overly ambitious tempo, yet had almost pulled off a win against a strong field and was only caught by Rod Dixon with the finish line in sight. He was passed by the Kiwi star with 400 left but held on to second place and collapsed at the finish.

In Boston 1984 Smith was on pace to smash the world record by 3 minutes at halfway, but faded over the second half of the race, though he held on to win this prestigious event. Though talented, he was unproven in major championships.

Hugh Jones was the 1982 London Marathon winner, where he ran a course record of 2.09.24. In 1983, he won Stockholm, finished second in Chicago (2.09.45) and was 8th in the World Championships. The redhead with the ungainly style was tough-as-nails and wore the British vest with pride.

Unassuming Durham pharmacist Charlie Spedding was a newcomer to the event, only making his debut in January that year when he narrowly won in Houston. He followed that up with a win in London (2.09.57) to secure his selection for LA. Never a star on the track or cross country (though he had been fourth over 10,000m at the Brisbane Commonwealth Games), the 32 year old had finally found his niche in the sport. He would make his mark here in California.

The Tanzanians:

Tanzania had success in the sport in the 1970s and early ’80s with Suleiman Nyambui and Filbert Bayi and now a new generation of runners were emerging as world class athletes.

Agapius Masong had a promising start to his career with a surprise 5th placing in the 1983 World Championships behind de Castella, running 2.10.42. At just 24, he appeared to have unlimited potential in the sport.

Gidamis Shahanga was de Castella’s predecessor as Commonwealth marathon champion and had a great pedigree on the track. He was Commonwealth champion over 10,000m and had finished 5th in a closely-fought World Championship 10,000m final the previous year.

He was in great form. Shahanga had won two marathons already that year, the Los Angeles Marathon (2.10.19) and Rotterdam (Shahanga won in 2.11.12 after Lopes, on world record pace for much of the race, had pulled out after 30km).

Tanzania’s main hope was the pint-sized Juma Ikangaa. Ikangaa’s breakthrough race in Brisbane 1982 – with his epic duel with Deek over the closing stages – saw him run 2.09.30 behind Deek’s long-standing all-comers record of 2.09.18 and established him as a star internationally.Though he was disappointing in the World Championships in 1983 with his 15th place, he had prepared well for LA and his aggressive style of racing had many experts identify Ikangaa as a real threat.

Rod Dixon (NZL):

Dixon was now 34 and after a successful career on the track and over cross country, he had been a huge name on the US road racing circuit for some years and he had turned to the marathon late in his career with remarkable success.

An accomplished cross country runner, Dixon had twice won bronze medals in the World Cross Country Championships (1973 & 1982).

The 1972 Olympic 1500m bronze medallist was a close 4th in the 1976 Olympic 5000m and he had missed the 1980 Games in Moscow due to New Zealand’s boycott.

Dixon had come into medal consideration after his incredible win in New York the previous year in running down Geoff Smith in the last few hundred metres inside Central Park. The canny veteran had not followed the long blue line as Smith had done, but rather had run the tangents of the curves in the road, minimising the distance he had to cover and had rapidly chewed into Smith’s huge lead over the final few miles.

The big Kiwi triumphed in a long-standing New Zealand record of 2.08.59. With over a decade of international experience and a range of world class ability from 1500m to the marathon, he had the potential to cause problems for the favourites.

Other Notable Athletes:

Somewhat of a late bloomer, Joseph Nzau was a 34 year old Kenyan who had established himself on the road circuit in the US, with wins in big races – most notably a narrow win over Hugh Jones in the 1983 Chicago Marathon in 2.09.45. He had only started running at 25 and earned a scholarship to Wyoming University and had developed in his running career by regular high level road races in the US, rather than run track or cross country.

He was one of the pioneers of Kenyan marathon running, as most Kenyan stars of the era were steeplechasers or 5000m/10,000m runners. There were no World or Olympic medallists in the event until 1987 and no Kenyan broke the world record until 1998.

Two Djiboutians, Djama Robleh and Ahmed Saleh were outsiders, but were both talented and another ‘x factor’ in the race.

Gerard Nijboer (NED) was the silver medallist from Moscow and was reigning European champion. Though he had run 2.09.01, he had been in a form slump in the previous year and was not expected to medal.

There were also two Belgians in the race with impressive backgrounds. Armand Parmentier was 6th in the World Championships and had won European silver behind Nijboer in 1982. Two time Olympic medallist Karel Lismont was back at the age of 35. Lismont was a great all-round distance runner, who had won bronze behind Treacy in the World Cross-Country in 1978, though he had not medalled internationally for some years.

As the athletes gathered at Santa Monica College for the start, the anticipation of something special was palpable. The race would more than live up to expectations.

In Part 2, The Race, we’ll take a deep dive into this all time classic marathon.

The author would like to thank Runner’s World, Let’s Run.com, Athletics Weekly online, the BBC, NBC (US), the New York Times and World Athletics.org.