A Column By Daniel Quin – Runner’s Tribe

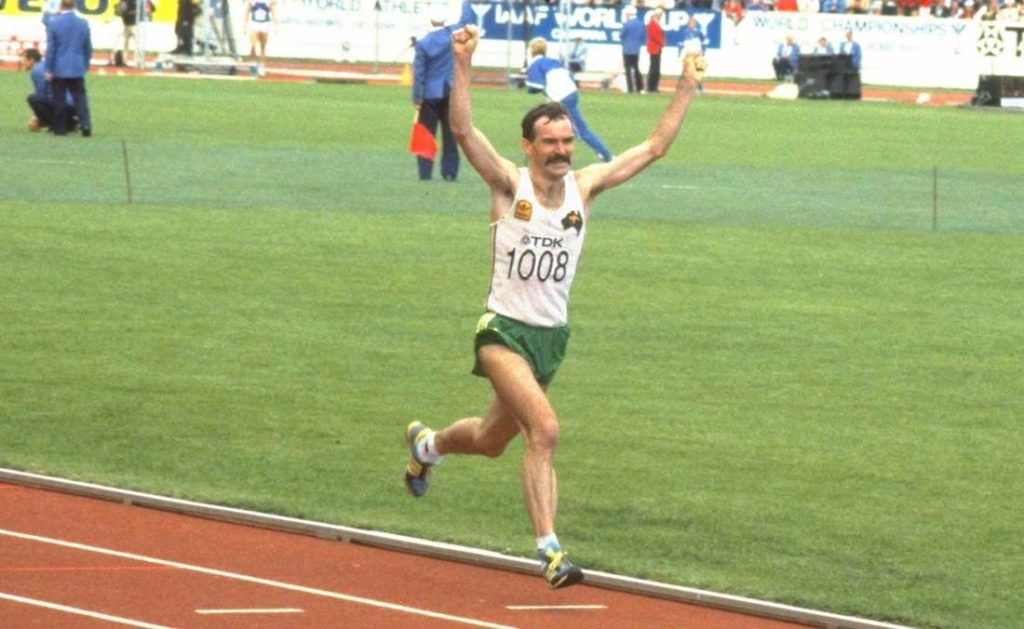

Recently I was reminded of a story about Robert DeCastella. Evidently he was reading a book on the bus that was taking him to the start-line of a major marathon. The visual image I create in my mind makes me smile – an assortment of nervous and sweaty marathoners, fidgeting and glancing at each other anxiously. In the midst of this I picture a big moustached Australian with hairy, tree-trunk legs pushing up against the rear of a seat, quietly oblivious to the mounting tension around him.

This story illustrates two points that I will elaborate upon: a) the potential for a wide range of anxiety or pre-race nerves and; b) the need to develop strategies to find the optimum level of pre-race arousal.

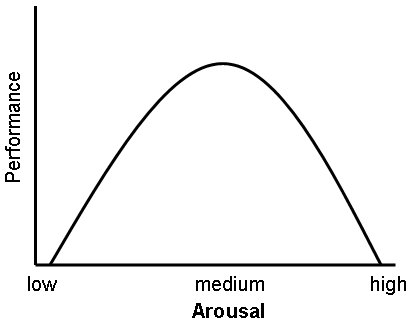

First, pre-races nerves or anxiety are not necessarily a problem. The key for any athlete is to find their optimum level of arousal. (Note for later: I have reframed anxiety into arousal.) One psychological theory proposes that athletic performance follows an inverted U (below).

An athlete on the extreme left of the graph could be described as lacking anxiety. They could be unmotivated, lacking focus, or apathetic about the upcoming race. At the extreme right an extremely anxious or overly aroused athlete is likely to be burning precious physical and emotional energy. It is possible that the over aroused athlete also lacks focus, but this is because he or she is over-analysing various race scenarios and outcomes.

The implication of this theory is that optimum pre-race arousal is as individual as an athlete. This is illustrated by the extremes of DeCastella and Usain Bolt pre-race. Bolt ‘s showmanship in an Olympic final can appear excessive to a distance runner. However, his pre-race showmanship is likely to be a coping strategy in response to heightened arousal under extreme stress. DeCastella, by contrast, withdraws and appears to conserve physical and emotional energy.

To put this concept to use athletes should start to observe their pre-race arousal and ideally, over time, identify their own optimum level of arousal. It is reasonable to expect natural variations between races. For example, Eloise Wellings may find it difficult to be sufficiently motivated before a low-key, local fun run. Alternatively, with years of experience she may find the peak of the inverted U (above) in an Olympic final with relative ease and run at her best.

So, how does an athlete adjust his or her arousal?

Reducing excessive nerves

- Instead of viewing your anxiety as a negative, recognise that nerves are an indicator that your body is getting ready for competition. In your mind reframe nerves as a positive and necessary step.

- Distract yourself. DeCastella’s book reading; Bolt’s showmanship; listening to music; etc. are simple distractions that take your mind off your race. Crucially, any distraction should be enjoyable to the athlete.

- Organise your thoughts. Sometimes worry arises when race plans or pre-race routines are unclear. Take the time, in advance, to write down race scenarios, equipment lists, pre-race time requirements, etc.

- Many athletes arrive at major competitions and self-doubt and negative thoughts start to creep in – a sign of anxiety. Be clear on your goals. Don’t become distracted by hype, buzz, pre-race chat. Why are you here?

- Go with the flow. Often anxiety arises when we try to control too many things that are out of our control. It is a skill to acknowledge a challenge and calmly accept it.

- Recognise and respond to thoughts, behaviours, and emotions. Are your thoughts starting to race out of control? Perhaps you are starting to fidget or pace. Or are you feeling out of control or scared? When you notice any of these happening try to take positive actions that reduce these signs of anxiety. Maybe deep breaths, a guided meditation, music, or talking to a trusted person can help bring these under control.

- Remain in the moment. Many athletes “catastrophise” and think of worst-case scenarios. Staying aware and in the moment is a form of mindfulness.

Increasing arousal

- Be clear on what you want to achieve from a race. Is it a time, effort, or place?

- Use a motivational play list or watch an inspirational clip.

- Visualise yourself running smoothly, attacking a hill, floating over the ground or a similar positive moment that you would like to achieve.

- Remind yourself of the feeling you have had when you finished a race, satisfied that you gave it all of your effort.

- Think about how an admired athlete, friend, or training partner would push through a flat spot or low motivation.

Don’t engage in negative things. If it is hot or windy, or a friend starts talking negatively there is little to be achieved from talking or thinking about this. Move on. What do you want to achieve?

END

About the Author: RT columnist, Daniel Quin has run numerous Zatopeks, National XC’s, has raced in a Chiba Ekiden, and won a state 5000m and 15km title. In “retirement” he did a marathon. It hurt! He still runs a fair bit. Professionally Quin is a teacher and psychologist, and researching student engagement- Click Here to Learn more. But the best bit for Quin is being a Dad.