By Len Johnson

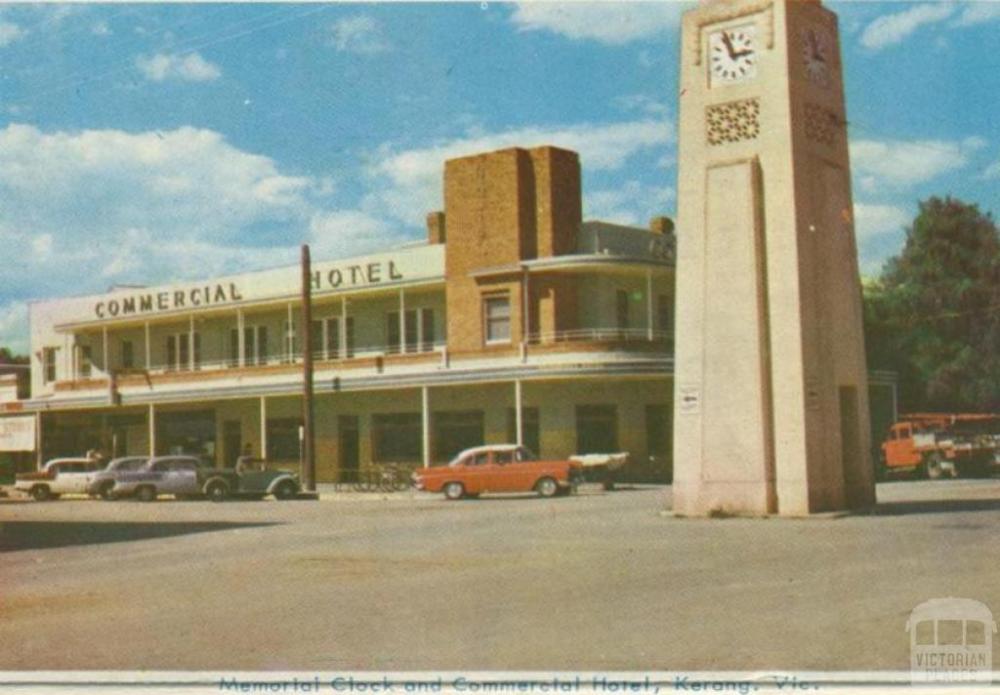

The Commercial Hotel in Kerang, a rural town in Victoria’s Mallee region, is as unlikely a site for a High-Performance Training Centre as you could find. Yet it may have a claim to being Australia’s first such facility.

That you could even make such a claim at all would largely be down to one man – Ray Weinberg, who was the publican at the hotel for 20 years through the 1950s and 1960s. More than that, Ray Weinberg was also a dual Olympian, representing Australia in the 110 metres hurdles at both London 1948 and Helsinki 1952, head coach and manager of Australian Olympic teams.

Victoria was ‘blessed’ with six-o’clock closing of hotels and bars back in those days, a policy which didn’t rank highly on anyone’s scale of social enlightenment. Rather than discourage drinking, it tended to cram it into an hour or less of frenzied and excessive consumption between the end of the working day and closing time.

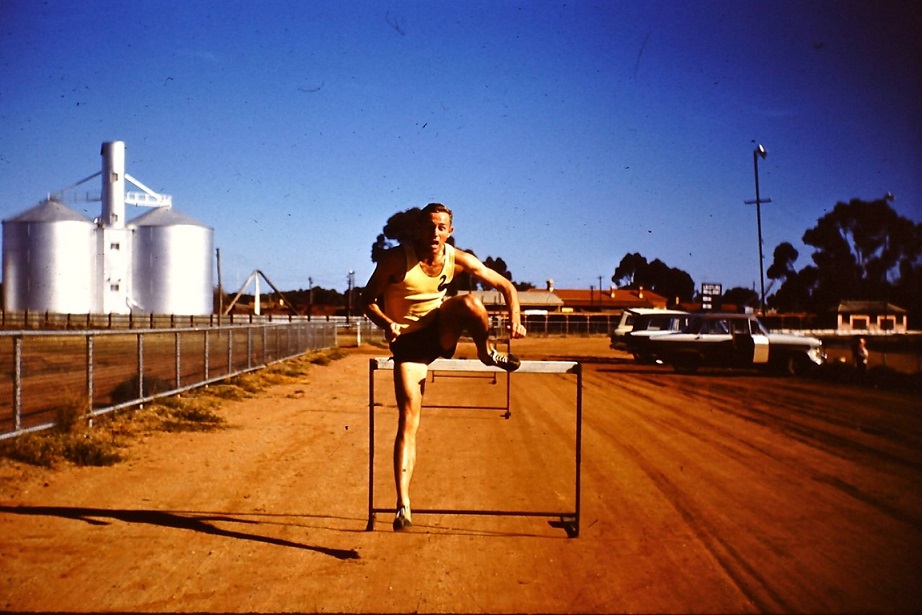

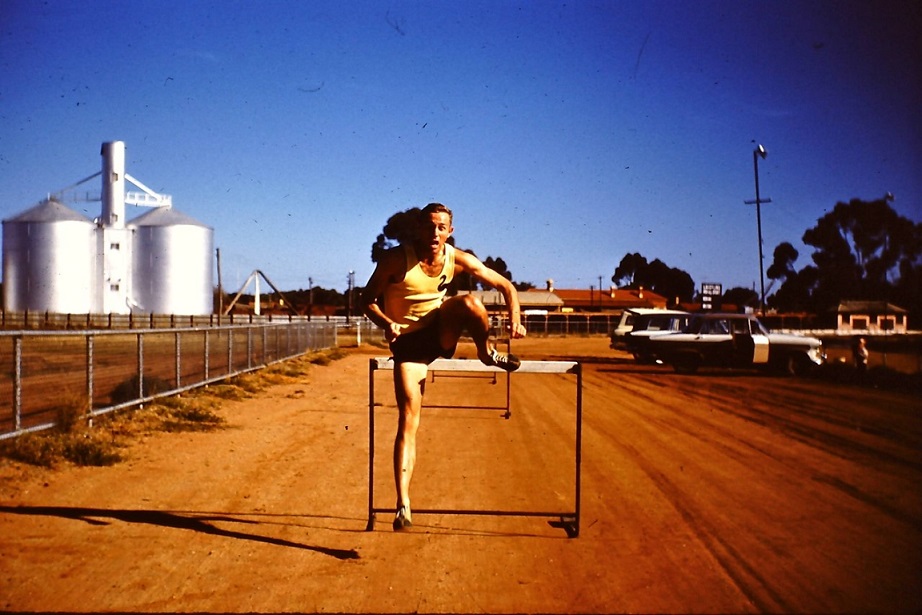

The silver lining of this cloud, however, was that Weinberg got to lock up and get his training done. He’d scrounged hurdles from here, there and everywhere and would set them up at the local Showgrounds or on the dead-flat expanses of nearby Kerang Airport.

Athletics is dotted with such stories of talented individual athletes virtually setting up their own training facilities – high jump pits in backyards, training tracks mown around empty fields, a gymnasium set up in a shed. Weinberg took things quite a few steps further, however. If Kerang meant isolation from the wider athletic world, then he would bring the wider athletic world to Kerang.

Enter the New Year amateur sports carnivals. Like most Victorian country towns, Kerang had an annual ‘pro’ meeting, which benefited from support from the local Council and businesses. Weinberg sold the carnivals to Council and businesses on the basis that he could get world-class athletes up to compete at almost no cost – an easy sell, his son, Brett, describes it.

John Landy competed at Kerang on New Year’s Day 1954, the year which saw him finally break four minutes for the mile. The Argus reported that “a strong south-westerly wind” cost him his chance of running a fast mile.

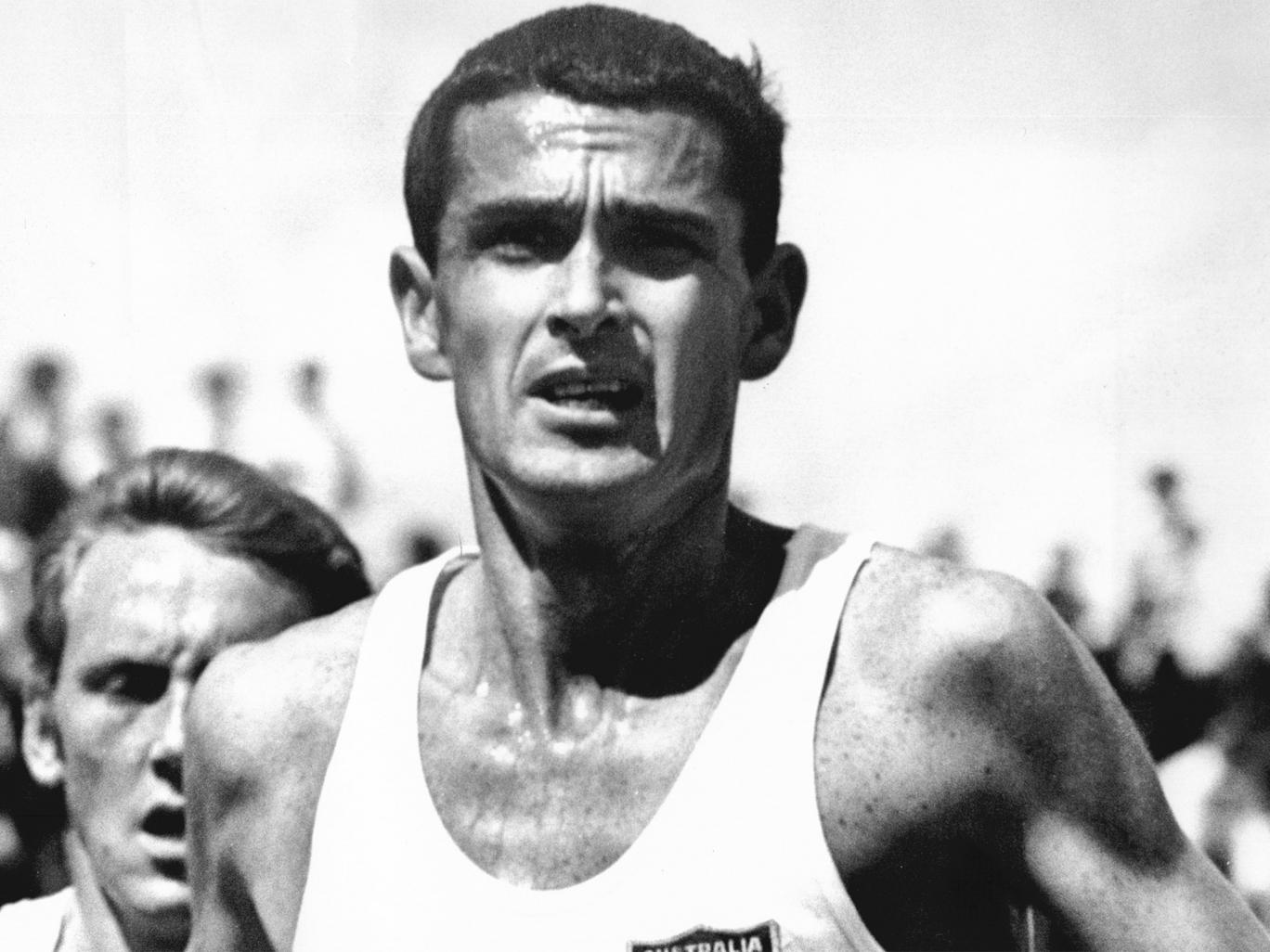

Another year, Ron Clarke came up with 1956 Olympic steeplechaser Neil Robbins.

Brett Weinberg, who provided much of this information, also backed the Commercial Hotel’s claims as a high-performance training centre. In a recent post to an online discussion group, Brett related the story of another Olympic hurdler – David Prince – who came to Kerang seeking Ray Weinberg’s advice.

‘Princey’ was a standout schoolboy athlete in the late ’50’s and early 60’s, Brett Weinberg wrote. My father was asked by a track publication to give a critique of David’s hurdling technique, and apparently, he was brutal. To the extent that my mother (Shirley Weinberg, nee Ogle, a Victorian champion sprinter) suggested he should write to David and provide some positive input.

David wanted to learn, and the only way he could achieve that was to come to the “Mecca of swamp birds and hurdling” – Kerang! Who knows how long the bus ride took him over those 180 miles!

I only ever did (the trip) by car when my father was going to Melbourne each weekend during the track season – off Friday night after the bar closed; compete in interclub Saturday; train Sunday morning; head home that afternoon.

My Dad had organised quite a few athletes to visit Kerang. John Landy made an attempt on the 4-minute mile at the Kerang Showgrounds in 100-degree heat, and survived. Percy Cerutty whipped the kids at Kerang Primary School up into an absolute frenzy, and promptly declared the rest of a day as a holiday.

D.P.’s training was often on the dirt carpark at the hotel, using a few of the ubiquitous hurdles that always seemed to be lying around everywhere, and when Dad could take time off from the bar. These were 6 o’clock closing days – “(Ring ring – If you can’t leave ‘em gentlemen, drink ‘em. If you can’t drink ‘em, leave ‘em. Ring ring.”) – so the drinking time was rather more compacted than it is now.

Like his mentor, D.P. learnt his trade on the trotting track at the Kerang Showgrounds. The surface, alleged to be “beautiful”, was said to have been gathered from along the river banks where there had been generations of campfires. Obviously a lot of campfires, as the track ran around the oversized footy ground.

My Dad had trained there as well, by himself as Kerang was bereft of hurdlers in the early ’50’s. (He) used the noise of the collision of railway trucks being shunted as his “gun” when practising starts. And, after the bar had closed and the glasses had been washed, out to the only really flat area of a really flat region, the airport. He’d put his hurdles up and train in the headlights of his car, whilst Mum watched and commented on his hurdling technique.

Prince’s aim was 1964 Olympic selection and it seemed to have paid off when an initial newspaper report included his name. Cruelly, it turned out he had been cut from the team by the notorious Justification Committee. Years later this had a poignant echo: as Athletics Australia president, Prince was involved in two team selection disputes, one with the Commonwealth Games Association in 1990 (which athletics won), the other in 1992 with the Australian Olympic Committee (which the sport lost).

That the effort failed was not against it.

“Whilst the training facilities were pretty rough,” Prince told Brett Weinberg, “your Dad taught me to run over the hurdles. His technical knowledge was outstanding and his ability to impart this hurdling skill was just brilliant.”

Actually, on closer examination, HPTCs were quite numerous in those days. There was Marjorie Jackson training in Lithgow by car headlights, John Landy carving out a furrow around Central Park, across the road from his family home, Percy Cerutty’s spartan, but sophisticated-by-comparison, International Training Centre at Portsea.

Just not as well resourced. Didn’t seem to hold anyone back much, did it?