By Brad Beer

How common is plantar fasciitis?

Plantar fasciitis is one of the most common causes of plantar heel pain in both runners and non-runners, and one of the most prevalent causes of foot pain in general with 10% of people experiencing plantar fasciitis across their lifespan (1). Plantar fasciitis affects both sedentary and athletic people. It is estimated that approximately 1 in 10 people experience heel pain at some point. Although plantar fasciitis occurs at all ages, the highest risk of occurrence of plantar fasciitis is between 40 and 60 years of age. There is no known sex bias.

A 2012 scientific literature review reported that plantar fasciitis was the third most common musculoskeletal injury to afflict distance runners who were in training, behind tibial stress syndrome (shin splints), and Achilles tendinopathy. Amongst runners, the incidence* of plantar fasciitis ranged from 4.5 to 10%, while the prevalence** ranged from 5.2 to 17.5% (1).

A 1996 paper that tracked running-related musculoskeletal injuries of ultramarathon runners found that plantar fasciitis was the most commonly reported injury in masters runners(2).

In the US it has been estimated to affect about two million people, resulting in more than one million visits to both primary care physicians and foot specialists (3,4).

*Incidence: the rate of newly diagnosed cases. It is generally reported as the number of new cases occurring in a period of time eg per month or per year.

**Prevalence is the actual number of cases either during a period of time (prevalence period) or at a given date (point prevalence).

How does plantar fasciitis present?

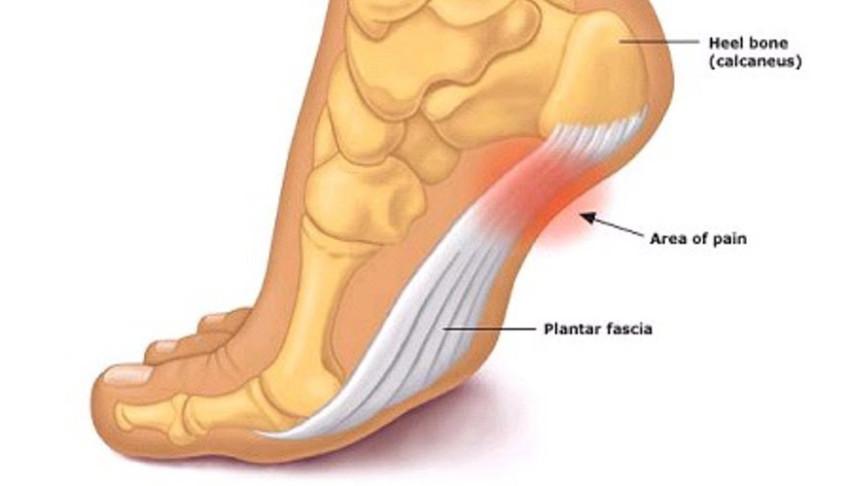

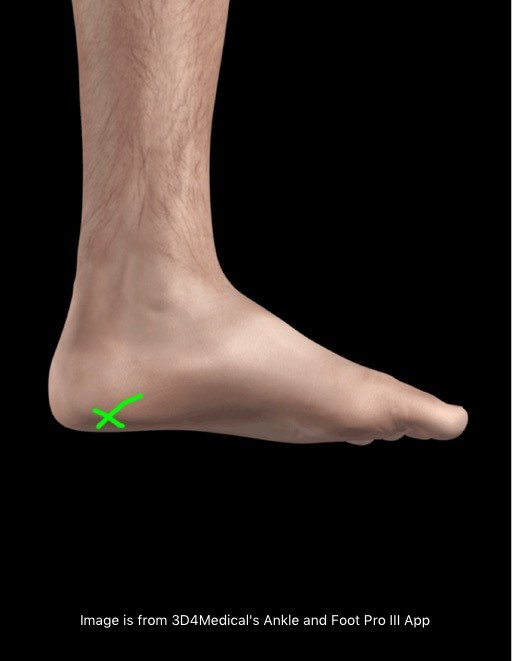

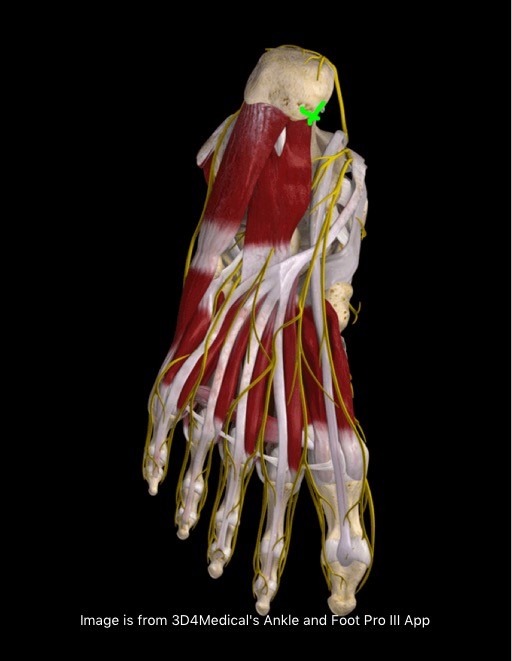

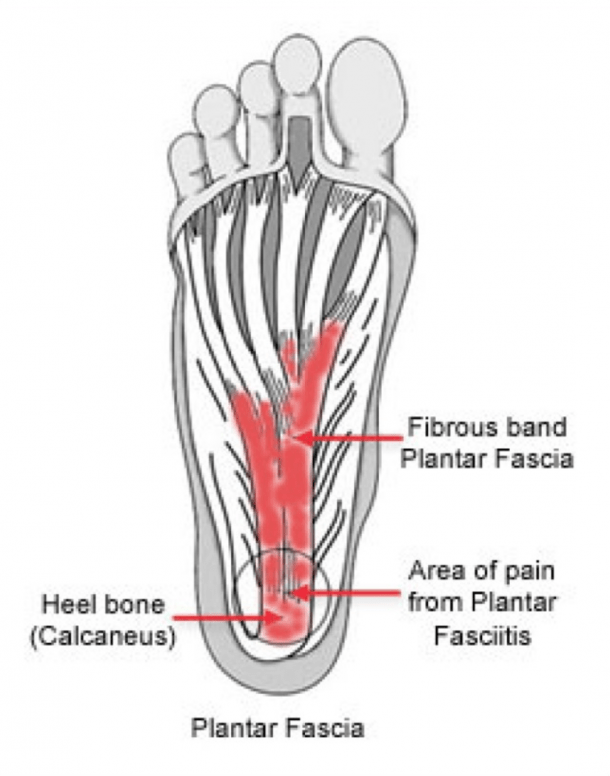

Plantar fasciitis presents with pain and tenderness being present and reported on the medial plantar aspect of the calcaneus (medial tubercle of the calcaneus). The insertion of the plantar fascia and the calcaneus (heel bone) is known as the fascial enthesis. See the green arrow below for typical location of plantar fasciitis pain.

Plantar fasciitis sufferers will typically experience:

- pain and stiffness on taking the first few steps on rising in the morning

- pain that increases with weight-bearing activities eg running, prolonged walking or standing etc

- The pain intensity can vary. At the mild end of the injury spectrum, the pain may be low grade and more of a feeling of stiffness. If the injury worsens the pain experienced can be very intense and is often reported as being ‘throbbing’ and sometimes even ‘stabbing’ in nature.

Specifically runners may experience the following:

- stiffness when commencing running that reduces as the runner warms up. This stiffness is similar to how tendon pathology ‘feels’ for runners in that a ‘stiff’ tendon ‘warms up’ after an initial period of discomfort when the runner commences as it effectively becomes a more efficient spring (fluid leaves the ground substance of tendon cells).

- Pain that increases with greater running loads (volume) and greater running intensity.

- Heightened pain and stiffness in the heel region 24 hours after exercise (ie the next morning).

What causes plantar fasciitis?

Although poorly understood the development of plantar fasciitis is believed to have a mechanical nature of onset whereby failure of the plantar fascia supporting the loads applied to the foot is commonly described as the chief mechanism of onset. Plantar fasciitis is also thought to result from chronic overload from either lifestyle or exercise (4).

A popular belief is that pes planus (flat) foot types and lower-limb biomechanics result in a lowered medial longitudinal arch, which is thought to create excessive tensile strain within the plantar fascia, in turn producing microscopic tears and chronic inflammation.

Histological evidence, however, does not support this commonly espoused belief as to the aetiology of plantar heel pain. Likewise support scientifically for the influence that arch mechanics has in the development of plantar fasciitis is equivocal at best, despite that anecdotal evidence would suggest a direct link between plantar fasciitis and a person’ arch function.

Injury to the plantar fascia can be acute or chronic in nature. While acute tears of the plantar fascia can occur in runners, the majority of cases are due to progressive and chronic overload and stress.

As with any running-related injury consideration needs to be given to risk factors such as running technique, training errors, running body strength deficits, adverse body tightness patterns, and running footwear selection, and the role that these various factors play in the onset of a running-related injury. For further details around how such risk factors can result in running-related injury refer to You CAN Run Pain Free! HERE>>

Known factors that can cause plantar fasciitis

Though plantar fasciitis can arise without an obvious cause, known factors that can increase a runner’s risk of developing plantar fasciitis include (5):

- Age. Plantar fasciitis is most common between the ages of 40 and 60.

- Certain types of exercise. Activities that place a lot of stress on the heel and attached tissue. Aside from running other activities can include jumping activities, ballet dancing, and aerobic dance.

- Foot mechanics. Flat-feet (pes planus), high arches, or an abnormal gait pattern can affect the way weight is distributed when statically standing and put added stress on the plantar fascia.

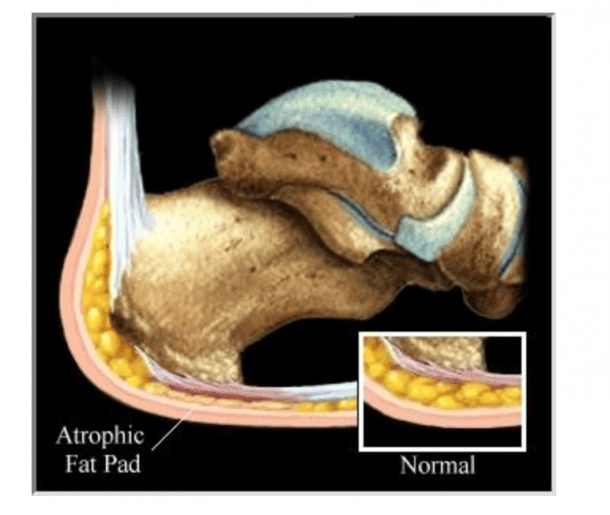

- Heel striking. When heel strike running occurs the loads at impact can be three times body weight. The ability to absorb and transmit such forces is dependant on the resilience of the plantar fascia, the plantar fat pad, and the plantar foot musculature (6).

- Increased body mass. Excess weight about an individual’s ideal frame weight can put extra stress on the plantar fascia. In the non-athletic population, the most common associated risk factor found in cross-sectional studies is increased body mass index (7). Researchers found a consistent association between body mass index and plantar fasciitis (fascioptahy). They noted that this association may differ between the athletic and non-athletic populations. This review also found that people with plantar fasciitis were more likely to have a thicker heel fat pad and subcalcaneal spur than those not suffering from plantar fasciitis. I have observed an increased body mass index to be a chief contributory factor over many years. I have observed when an individual’s body weight increases that their risk of developing heel pain markedly increases. To learn more about the role of body weight on injury please click through >> Those extra few kilograms do matter when it comes to injury

- Only one prospective risk factor study has been conducted for plantar fasciitis in the athletic population which investigated a cohort of 166 recreational and competitive runners (8). This study found a varus hindfoot (see below image), a varus knee position (see below), a cavus foot type (see below), spiked footwear and middle distance running to be the chief risk factors for the onset of plantar fasciitis.

- Occupations that require people to be on their feet for prolonged periods of time. Factory workers, teachers, and others who spend most of their work hours walking or standing on hard surfaces are potentially more susceptible to the onset of plantar fasciitis.

- Further research is required to determine the importance of such factors as vascular and metabolic disturbances, the formation of free radicals, hyperthermia, and the potential role of genetics in the onset and development of plantar fasciitis.

Plantar Fasciopathy/fasciosis

Current literature suggests that plantar fasciitis is more correctly termed fasciosis or fasciopathy because of the chronicity of the disease and the evidence of degeneration rather than inflammation (3,4). There are known overlaps of how the plantar fascia and tendons respond to loading and pathology.

For the purpose of familiarity, I will refer to the condition as plantar fasciitis for the remainder of this blog post and stay clear of using the term plantar fasciopathy or fasciosis.

Diagnosing plantar fasciitis

I find that diagnostically a sound clinical history coupled with positive tenderness findings with palpation of the medial calcaneal tubercle are the key two diagnostics used to accurately diagnose plantar fasciitis.

Diagnostic imaging is not helpful in diagnosing plantar fasciitis, but it should be considered if another diagnosis is strongly suspected (7). According to several small case-control studies that compared patients with and without plantar fasciitis, thicker heel aponeurosis, identified by ultrasonography, is associated with plantar fasciitis (7).

Radiography may show calcifications in the soft tissues around the heel or osteophytes on the anterior calcaneus (i.e., heel spurs). Fifty percent of patients with plantar fasciitis and up to 19 percent of persons without plantar fasciitis have heel spurs. The presence or absence of heel spurs is not helpful in diagnosing plantar fasciitis (7).

Bone scans can show increased uptake at the calcaneus, and magnetic resonance imaging can show thickening of the plantar fascia. However, the accuracy of these tests remains inconclusive (7) and I find that they are typically not required in order to make an accurate diagnosis.

In long-standing cases that are not responding to the appropriate treatment I may send a patient for an MRI scan to assess for any other potential causes of their symptoms which are outlined below:

Differential diagnosis of plantar fasciitis

An array of pathologies can give rise to pain beneath the heel, including vascular, neurological, arthritic and malignant aetiologies. Once such conditions are excluded a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis remains.

It is important to be aware of the below conditions that can present in a similar fashion to plantar fasciitis, but whose management will differ:

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome: Tarsal tunnel syndrome is the most common nerve entrapment syndrome in the ankle. It is analogous to ‘carpal tunnel syndrome’ in the wrist. It is also known as posterior tibial nerve neuralgia, in which the tibial nerve is compressed as it runs through the tarsal tunnel.

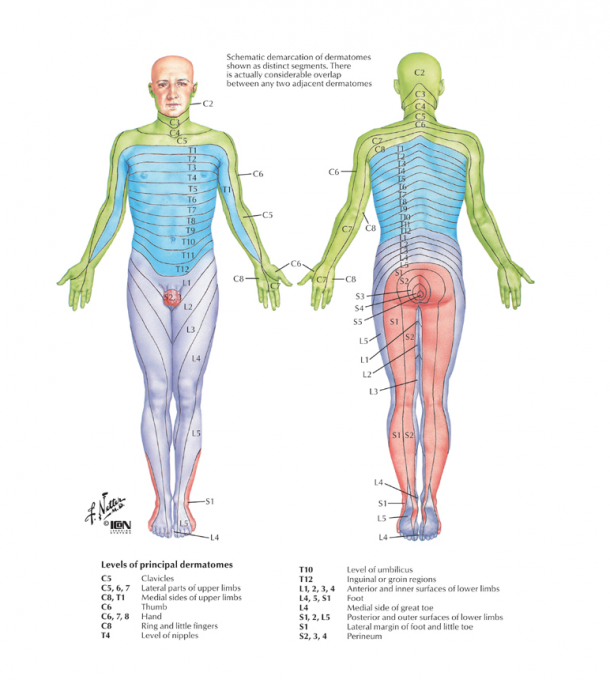

- L5/S1 radiculopathy: this is pain referred from the lumbar spine at the level of the exiting L5/S1 nerve roots. This may be due to disc injury (disc protrusion, or extrusion) or localised lumbar spine vertebral changes (osteoarthritis of the facet joints, or narrowing of the exit foramina for the nerves), or spinal nerve root irritation of L5/S1. See the below image from Netter: Atlas of Human Anatomy for the region innervated by the L5/S1 nerve roots.

- Calcaneal stress fracture or stress reaction: Stress reactions of the heel bone (calcaneus) can be missed in the running or repetitive load-bearing athlete. Pain that progresses over time from a ‘bruised heel’ sensation to more severe pain (ie unable to hop on the foot) should be noted and a suspicion for bony stress injury should be held with appropriate investigations to follow.

- Fat pad irritation or atrophy: A fall onto the heel from a height or chronic heel striking can result in decreased elasticity of the heel fat pad (see below image for fat pad covering the plantar fascia). Fat pad related pain is typically felt more on the outer side of the calcaneus. MRI imaging may reveal changes in the fat pad showing signs of swelling. in cases where a sufferer of plantar fasciitis may have had repeated cortisone injections as a method to reduce pain the fat pad may have atrophied (shrunken or been ameliorated-see below image).

Source: http://www.footpainreliefstore.com/library/fatpadatro.htm

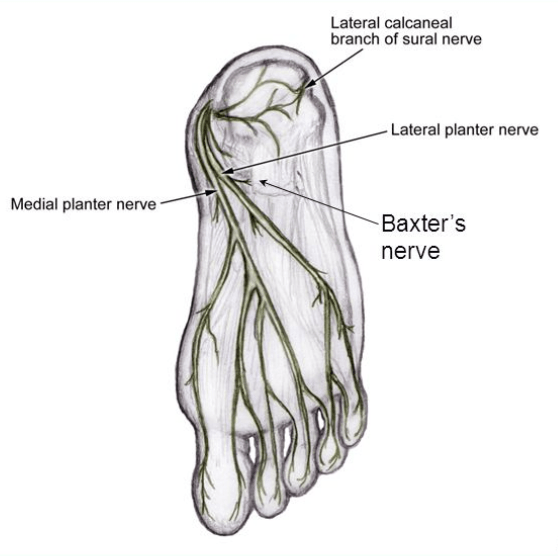

- Baxter’s nerve impingement: One of the more elusive causes of plantar heel pain can be entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve, known as Baxter’s nerve impingement. Baxter’s nerve provides motor innervation for the abductor digiti minimi muscle. It also has a sensory nerve function. Baxter’s nerve impingement can produce symptoms that are indistinguishable from plantar fasciitis. While it may account for up to 20% of all plantar heel pain presentations, it is often overlooked for other causes of heel pain. Muscle changes can be seen in the abductor digiti minimi muscle to assist diagnosis of Baxter’s nerve impingement. If conservative management for the treatment of Baxter’s nerve impingement fails surgical outcomes are normally good. For further reading click HERE>>

Source:http://slideplayer.com/slide/5663811/

Prognosis of plantar fasciitis

Most people suffering from plantar fasciitis will in time improve. Timeframes can vary from a few weeks of mild discomfort to years of debilitating morning stiffness and pain. In my years in practice, I have treated patients with short term discomfort and others who have endured pain and symptoms for years.

In one long term study researchers (8) found that 80% of patients treated conservatively for plantar fasciitis had complete resolution of pain after four years. While this finding is not very exciting, I have observed that the average recovery time in practice tends to be somewhere between three and six months.

Treatment Options for plantar fasciitis

General rehabilitation journey

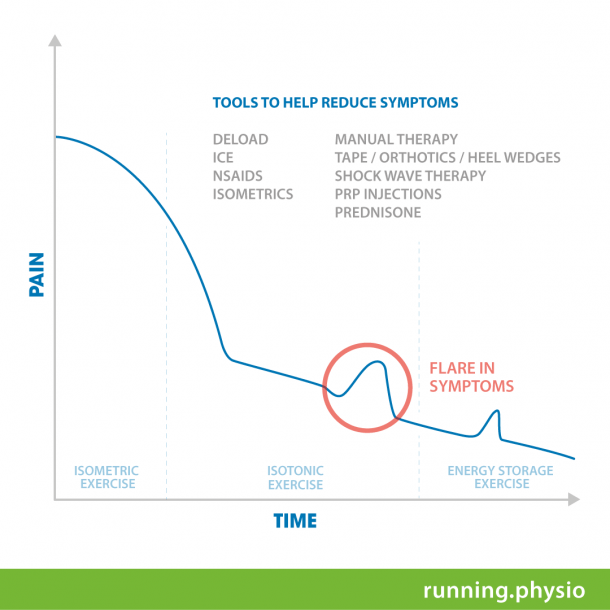

Rehabilitating plantar fasciitis has many similarities with the treatment and rehabilitation of tendon conditions and specifically tendinopathies. The below diagram is one I use as an education tool in the treatment of lower limb tendinopathies. It provides a general ‘Recovery Roadmap’ of what can be expected with the rehabilitation journey for lower limb tendon conditions. This roadmap for tendon rehabilitation is useful for us to consider in understanding the general rehabilitation journey required to resolve plantar fasciitis. Let’s explore a few key Recovery Roadmap insights:

Phase I: Reducing Pain/Symptoms

In essence, the first stage of rehabilitation is to attempt to reduce pain and symptoms as quickly as possible.

This desired rapid reduction in symptoms is depicted in the diagram by the ‘steep drop off’ of pain shown on the left side of the diagram. I refer to this desired rapid reduction in pain and symptoms with patients as trying to ‘throw the pain off a cliff’. Clients receiving treatment for their condition appreciate this notion and on citing the graph can conceptualise what the rehabilitation is initially targeted toward and trying to achieve.

Phase II: Rehabilitation through load management and exercise rehabilitation

The second stage of the rehabilitation journey is to rehabilitate the affected structure and tissues through a staged and progressive exercise-based program, coupled with strategies to appropriately load the plantar fascia while it is recovering. It is during this part of the rehabilitation journey that the individual can expect to experience ‘flare-ups’ from time to time in symptoms as is illustrated by the ‘bumps’ in the recovery line.

These flare-ups of symptoms typically get less and less over time and when they occur hopefully are of less and less intensity.

What works and what doesn’t in the treatment of plantar fasciitis?

Plantar fasciitis is usually treated conservatively (non-surgically) and there are many recommended interventions.

Below are the common treatment approaches used for plantar fasciitis and the supporting evidence for and against each treatment option.

1. Shock wave therapy

Like many adjunctive and passive therapies, many people hope that their rehabilitation can be largely ‘passive‘. That is they hope that their solution ‘fix’ or ‘cure’ will be found in something that can be ‘done to them’, as opposed to needing to ‘do something’ themselves to improve function and reduce symptoms. (I understand this inclination and desire -I’d prefer a passive approach rather than an active approach to many of life’s problems!)

Shock wave therapy falls into the category of ‘passive therapy’. Some plantar fasciitis sufferers sing the praises of shock wave therapy, while others may report negligible or little reduction in their pain or symptoms following receiving shock wave therapy treatment.

Let’s take a look at what the literature reveals about the effectiveness of shock wave therapy in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

There is conflicting evidence concerning the role of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in the management of plantar fasciitis.

Two literature reviews (9, 11) compared ESWT with a placebo procedure in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. Neither study found a significant difference between the treatment and control groups three months after treatment. One of these reviews (11) included 45 runners who had chronic heel pain for more than 12 months. According to the study, three weekly treatments of ESWT significantly reduced morning pain in the treatment group at six and 12 months when compared with the control group.

A 2014 systematic review looked at 550 subjects across 7 papers that looked at the effect of ESWT on chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis (12). For pain relief a significant difference was found between the ESWT group and the control group. For function, only low-intensity ESWT was significantly superior over the control treatment.

A 2017 systematic review of the literature further validated the use of ESWT for chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. This review included 9 studies in the analysis which compared ESWT to placebo in the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis in adults. The authors of the review concluded that compared with placebo, ESWT significantly improved the success rate of reducing overall heel pain, reducing the self reported pain scores by 60% for the first step in the morning and during daily activities, and reducing heel pain after application of a pressure meter. The paper concluded ESWT seems to be particularly effective in relieving pain associated with RPF (12).

Meanwhile a further systematic review of the literature looked at the effect of the different forms of shock wave therapy (general, focussed, and radial) for the treatment of plantar fasciitis compared to placebo (14). 9 studies including 935 subjects were included. The results suggested that focused shock wave therapy can relieve pain in chronic plantar fasciitis as an ideal alternative option; meanwhile, no firm conclusions of general shockwave therapy or radial shock wave therapy effectiveness could be drawn.

Recommended Reading: To read more about the role of shock wave therapy in the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions click HERE>> or HERE>> Shock Wave Therapy: Does it Work?

Take home: in clinical practice at POGO Physio, we have an ESWT machine available. Where a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis has been made I will administer ESWT to the patient with the explanation that we will repeat a follow up the dose if they experience reduced symptomatology in the following 48 hour window. However, if the patient does not report a notable and positive reduction in symptoms (pain or stiffness) than a further application of ESWT may be administered or it may be reasoned to not try again. This is as per Peter Malliaras’ approach for using shock wave therapy in the treatment of lower limb tendinopathies. Other interventions are included in my treatment alongside the administration of the shock wave therapy. If a plantar fasciitis sufferer has the ability to access shockwave therapies I would suggest that they trial the treatment, while combining it with other approaches such as exercise therapy as will be detailed below.

2. Foot orthotics (shoe inserts/foot orthoses).

The rationale for the use of orthotics for people with plantar fasciitis is unclear due to scant research specific for this condition. There is some evidence that foot orthotics reduce peak plantar pressures at the heel in plantar fasciitis sufferers, and that they may decrease strain (15). Studies not specific to plantar fasciitis have found that foot orthotics modify tissue loads by altering kinematics, kinetics, muscle activity and sensory feedback.

The effect of foot orthoses on plantar fasciitis pain and function have until recently been scientifically unclear and inconsistent. One meta-analysis concluded that there was insufficient evidence that customised foot orthotics reduced pain compared with sham (non-customised) foot orthotics at the 12 week mark, while another meta-analysis concluded that foot orthotics decreased both pain and improved function in the short (<6 weeks), medium (6-12 weeks), and longer (>12 weeks) term.

A recently published systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the effectiveness of foot orthotics on the pain and function in adults suffering from plantar heel pain (plantar fasciitis) (16).

A total of 19 trials (1660 participants) were included in the review. The findings were:

- In the short term (<7 weeks) there was very low-quality evidence that foot orthotics reduce pain or improve function.

- In the medium-term (7-12 weeks) there was moderate-quality evidence that foot orthotics were more effective than sham foot orthotics at reducing pain. There was no improvement in function in the medium term.

- In the longer term (>12 weeks) there was very low-quality evidence that foot orthotics reduced pain or improved function.

The above short, medium, and long term findings led the researchers to conclude that there is moderate quality evidence that foot orthotics are effective at reducing pain in the medium term, however it remains uncertain whether this is a clinically significant change.

In other words if orthotics are prescribed for plantar fasciitis sufferers the user may expect to experience some pain relief at around the 6-12 week mark, but not necessarily experience any improvement in function.

The study also showed that at the time a comparison of customised and prefabricated (off the shelf) foot orthotics showed no difference.

Take home:

I will typically work with patients to address their symptoms by deloading the affected area, commencing strengthening exercises, and monitoring symptoms while concurrently assessing and exploring the possible need for orthotic intervention. In cases where I feel that a detailed foot assessment may be required I may refer to a skilled podiatrist or simply trial some cost-effective off the shelf orthotics.

3. Load management

Deloading is the mainstay of load management in the initial treatment of plantar fasciitis. De-loaodng of the affected foot means reducing the impact loading the foot is experiencing. There are no set ‘rules’ or scientifically established best protocols for how exactly to deload a plantar fasciitis sufferers foot. It is more done on ‘feel’ and symptom response as directed by the treating practitioner.

One approach is to reduce the loading by half. For example take a runner suffering from persistent plantar fasciitis who has been running 50kms per week. One approach to reducing the loads on the symptomatic foot could be to reduce the runner’s running volume immediately by 50%, to running 25kms per week. If symptoms remain unchanged than a further reduction of 50% in running volume may be required. If symptoms remain with these two 50% reductions in then complete rest may be required. The same deloading principles can apply to non-runners suffering from plantar fasciitis. For example a worker who stands on their feet all day may find it helpful to reduce their standing time at work, to potentiate a reduction in symptoms.

4. Exercise Therapy

Exercise therapy forms the mainstay of the approach I take in guiding patients to recover from plantar fasciitis. I have observed it to be effective both clinically and it is also well supported in the scientific literature. When combined with appropriate pain-relieving strategies such as deloading of the foot through activity modifications, and the appropriate exercises are prescribed at the appropriate time with compliance from the patient the results are good.

- Plantar Fascia strengthening exercise

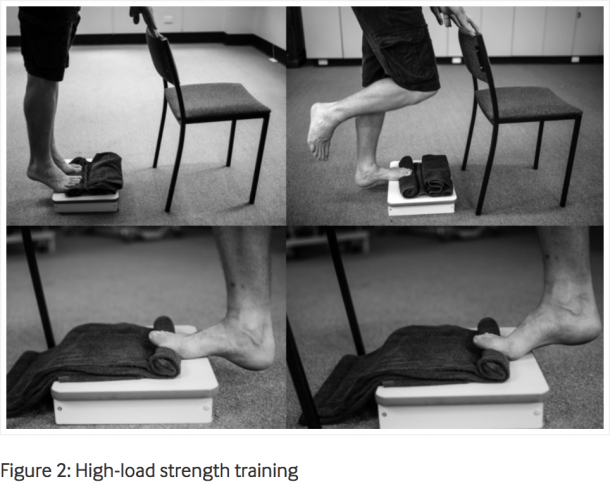

In 2014 Rathleff et al. (21) found a progressive heavy loading exercise program using a modified calf raise (with a towel under toes) effective in treating plantar fasciitis. With the understanding and supporting research that high load strength training had been shown to be effective in the treatment of tendinopathies, Rathleff et al. sought to determine if the same principles could be applied to the treatment of plantar fasciitis. The study comprised 48 patients with plantar fasciitis that received either high load strength training or plantar fascia stretching exercise

Rathleff and colleagues investigated the effect of a high-load strength-training program compared to a standard plantar specific stretching program in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Their aim was to enhance the work being performed by the plantar fascia through modifying a single leg calf raise by placing a towel under the toes. See the exercise and placement of the towel under the toes as it was depicted in the research paper below:

The subjects were asked to complete the exercise every second day for 12 weeks.

The raises were completed as:

- 3s on way up (concentric phase)

- 2s hold at the top (isometric phase)

- and a 3s lowering down (eccentric phase), giving a total of 8s per repetition.

To view the exercise being performed see below:

The high-load strength training was slowly progressed through the study as follows:

Weeks 1-2: 3x 12 reps (every second day)

Weeks 2-4: 4x10reps adding books to a backpack to make heavier.

Weeks 4+: 5x 8reps adding books to a backpack to make heavier.

The results of the study (21) were as follows:

- The Foot Function Index was used as the outcome measure to determine the effectiveness or otherwise of the interventions: stretching or strengthening.

- At 3 months: the subjects that did the high load strength exercise had a 29 points lower Foot Function Index. This can be deemed to be far superior compared to the outcomes of the plantar fascia stretching.

- No differences were noted between the stretching and strength exercise groups at the 6 and 12-month marks, indicating no superior long term outcome of the strengthening exercise over the stretching exercise.

- Given that the strengthening exercise was shown to provide a quicker reduction in pain than stretching this is clinically the exercise I tend to prescribe for plantar fasciitis sufferers.

As to why the high load strengthening exercise was effective for the treatment of plantar fasciitis there are several proposed theories. They are as follows:

- The high loading may stimulate increased collagen synthesis and thereby facilitating more normal structure of the tendon. With this improved structure, the plantar fasciia develops better load tolerance and therefore better outcomes.

- Increased ankle dorsiflexion ROM, and improved intrinsic foot muscle strength.

Related: A university colleague of mine recently released the Fasciitis Fighter as an alternative to using a rolled up towel for high-load strength training for plantar fasciitis. Check out the design below or jump over to the Fasciitis Fighter webpage for more information.

- Other exercises

It is important to not just strengthen the plantar fascia itself but to also strengthen associated structures such as the calf complex (gastrocnemius and soleus muscles) and the entire kinetic chain.

For runners this may include the completion of exercises such as:

- Calf raises

- Soleus raises

- Gluteal exercises (bridging, fire hydrants, single leg romanian deadlifts, sit to stands etc).

- Balance/ proprioception based exercises: these may include exercises such as ‘Leyton Hewitts’ and single leg balance drills.

Later stage exercises tend to be more focussed on higher load strength and power gains, which may include plyometric (jumping) based exercises.

5. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections

Platelet-rich plasma is an autologous blood product consisting of plasma enriched with a concentration of platelets that is greater than that of whole blood, typically at least 4 times the baseline value.

PRP has grown in popularity in recent years as a way to accelerate healing of a variety of musculoskeletal conditions.

Platelets are thought to be important for the healing of injured tissue. They are enriched with multiple growth factors, cytokines, growth factors, and other factors. These proteins are thought to augment tissue healing when delivered locally. It seems to work through inducing local tissue inflammation.

A 2017 (22) meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials compared the safety and effectiveness of PRP therapy compared with the safety and effectiveness of steroid injections.

They reported that there was no significant difference in pain scores at 4 (short term) and 12 weeks (medium-term) post PRP or steroid injections. However, 24 weeks after the interventions those plantar fasciitis sufferers who received PRP injection treatment reported lower pain scores than those who received steroid injection therapy.

The authors concluded that limited evidence exists to suggest that PRP is superior to steroid injection for long term pain relief of plantar fasciitis.

There exists a paucity of scientific evidence to support the use of PRP injections in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Database reviews of studies that looked to assess the efficacy of PRP for plantar fasciitis treatment found only small sample size uncontrolled prospective studies. Some of which showed some positive results (23).

Related reading:

Take home: Clinically I tend to initially dissuade patients going down the route of PRP injection therapy until appropriate load management and exercise prescription interventions have been implemented. For many plantar fasciitis sufferers that are aware of PRP injection therapies, the idea of a passive ‘fix’ can be very appealing. If cases are recalcitrant to improve and the patient has been compliant with the rehabilitation program, and other causes have been ruled out (see Differential Diagnosis) than it may be indicated and if the patient is prepared to spend the money than there is nothing to lose.

6. Acupuncture

A 2012 systematic review (24) of the effectiveness of acupuncture for plantar fasciitis concluded that there is evidence to support the use of acupuncture in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. The authors suggested that acupuncture should be considered as a treatment option for plantar fasciitis.

Take home: Clinically I tend to avoid the use of acupuncture for plantar fasciitis. This is based on the high discomfort and often time anxiety levels that the treatment can induce for the patient.

7. Surgery

As there are no data from high-quality, randomized, controlled trials that support the efficacy of surgical management. The most prudent and I believe a wise approach is to employ conservative modalities such as load management strategies ang graded exercise prescription first. Surgical treatment is typically only considered in a small subset of patients with persistent and severe symptoms. In my 12 years a physiotherapist I have only observed one patient go to surgery for plantar fasciitis.

8. Night splints

Posterior tension night splints such as the Strasburg Sock were very popular circa 2005-2010. They seem to be less commonly referred to by both practitioners and also patients or plantar fasciitis sufferers in recent years. The socks maintain ankle dorsiflexion and toe extension which facilitates a constant mild stretch of the plantar fascia, purportedly allowing the plantar fascia to heal at a functional length.

See below for how the sock is worn and click HERE>> to learn more about using the Strasburg Sock.

One Cochrane review (25) found limited evidence to support the use of night splints to treat plantar fasciitis sufferers who had experienced pain for greater than 6 months. They found that patients treated with custom made splints improved but those with premade or ‘off the shelf’ splints did not.

Take Home: I have observed night splints to be of very little clinical value over my years as a physiotherapist. Hence I typically would not recommend plantar fasciitis sufferers use them.

9. Gel inserts

The use of gel inserts may be useful in deloading the affected plantar fascia tissue. In cases where the pain levels are marked and the patient’s function is considerably compromised I will suggest that the patient trials the use of the gel heel inserts in both their running shoes and also their day shoes.

There exists no scientific evidence for the use of gel heel inserts in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. It, therefore, appears to be a practice that has been used for decades based on the ‘commonsensical’ notion of putting something soft under the heel to assist with reduction in plantar fasciitis symptoms.

10. Steroid injections

Limited evidence supports the use of corticosteroid injections to manage plantar fasciitis. It is commonly performed for the treatment of plantar fascia pain and inflammation.

A 2012 study looked at the effectiveness of ultrasound-guided cortisone injections in the treatment of plantar fasciitis (26). They found a greater reduction in pain for the cortisone vs placebo control group at four weeks, but no difference in pain scores between 8 and 12 weeks. They concluded that a single ultrasound-guided cortisone injection is a safe and effective short term treatment for plantar fasciitis. It provides greater pain relief than placebo at four weeks and reduces abnormal swelling of the plantar fascia for up to three months. However, clinicians offering this treatment should also note that significant pain relief did not continue beyond four weeks.

A degree of caution needs to be had before administering cortisone injections for plantar fasciitis as corticosteroid injection is associated with plantar fascia rupture and ongoing associated discomfort. However, the risk of plantar fascia rupture following cortisone injection is generally low (27).

Take home: I tend to encourage plantar fasciitis sufferers to avoid or delay cortisone injections for pain relief as long as possible while load management and exercise prescription strategies are put in place. A decision to proceed with an injection as part of the overall rehabilitation plan needs to be made on a case by case basis.

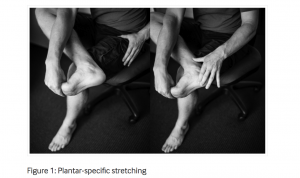

11. Stretching

Stretching protocols for plantar fasciitis tend to focus on the calf muscles, or the plantar fascia itself.

In a prospective randomised control trial that compared calf to plantar fascia stretches, researchers found that patients who stretched the plantar fascia (as depicted below) showed a greater decrease in ‘pain at its worst’, and with ‘first steps’ pain in the morning. The stretch was to be completed 3x day as 10 reps of 10-second holds. However, both the plantar fascia specific stretching and the calf stretching groups experienced an overall reduction in plantar heel pain (28).

The plantar fascia specific stretch may help improve ankle dorsiflexion and great toe extension range, both of which have been cited as potential risk factors for plantar fasciitis.

Take home: I will often include plantar fascia specific stretching as part of an overall rehabilitation program. As the program progresses I find that the need to stretch typically reduces.

Final thoughts

While the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is relatively straight-forward the rehabilitation of plantar fasciitis tends to be less so. It is important to be guided by a skilled practitioner who understands the pathology and is up to speed with the current best practices and treatment approaches. It is also important to remain patient and take a longer-term approach to resolve symptoms and regain full functional capacity. Failure to do so will typically leave the plantar fasciitis sufferer frustrated and confused.

If you have any questions about your recovery from plantar fasciitis please feel free to leave them below and I will reply as I am able.

Physio With a Finish Line™,

Brad Beer (APAM)

Physiotherapist (APAM)

Author ‘You CAN Run Pain Free!’

Founder POGO Physio

Host The Physical Performance Show

Featured in the Top 50 Physical Therapy Blog

References

- Lopes, A.D., Hespanhol, L.C., Yeung, S.S. et al. Sports Med (2012) 42: 891. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03262301

- Fallon KE. Musculoskeletal injuries in the ultramarathon: the 1990 Westfield Sydney to Melbourne run. Br J Sports Med 1996 Dec; 30(4): 319–23.

- Young C. In the clinic: plantar fasciitis. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 3;156(1 Pt 1) TC1-1, ITC1-2, ITC1-3, ITC1-4, ITC1-5, ITC1-6, ITC1-7, ITC1-8, ITC1-9, ITC1-10, ITC1-11, ITC1-12, ITC1-13, ITC1-14, ITC1-15; quiz ITC1-16. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-01001. [PubMed]

- Dyck DD, Jr, Boyajian-O’Neill LA. Plantar fasciitis. Clin J Sport Med. 2004 Sep;14(5):305–9. DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00042752-200409000-00010. [PubMed]

- https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/plantar-fasciitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20354846

- Scott C. Wearing, James E. Smeathers, Stephen R. Urry, Ewald M. Hennig, Andrew P. Hills,The pathomechanics of plantar fasciitis. Sports Med. 2006; 36(7): 585–611.

- K. D. B. van Leeuwen, J. Rogers, T. Winzenberg, M. van Middelkoop. Higher body mass index is associated with plantar fasciopathy/’plantar fasciitis’: systematic review and meta-analysis of various clinical and imaging risk factors.. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Aug; 50(16): 972–981. Published online 2015 Dec 7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094695

- Di Caprio F, Buda R, Mosca M, Calabro’ A, Giannini S. Foot and Lower Limb Diseases in Runners: Assessment of Risk Factors. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2010;9(4):587-596.

- Plantar Fasciitis: Evidence-Based Review of Diagnosis and Therapy CHARLES COLE, M.D., CRAIG SETO, M.D., and JOHN GAZEWOO

- Wolgin M, Cook C, Graham C, Mauldin D. Conservative treatment of plantar heel pain: long-term follow-up. Foot Ankle Int 1994;15:97-102.Crawford F, Thomson C. Interventions for treating plantar heel pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(3): CD000416.

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciitis. A double blind randomised controlled trial. J Orthop Res 2003;21:937-40.

- Rompe JD, Decking J, Schoellner C, Nafe B. Shock wave application for chronic plantar fasciitis in running athletes. A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:268-75.

- Haake M, Buch M, Schoellner C, Goebel F, Vogel M, Mueller I, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciitis: randomised controlled multicentre trial. BMJ 2003;327:75

- Aqil A1, Siddiqui MR, Solan M, Redfern DJ, Gulati V, Cobb JP. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013 Nov;471(11):3645-52. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3132-2. Epub 2013 Jun 28. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is effective in treating chronic plantar fasciitis: a meta-analysis of RCTs.

- G. F. Kogler, S. E. Solomonidis, J. P. Paul. Biomechanics of longitudinal arch support mechanisms in foot orthoses and their effect on plantar aponeurosis strain.Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 1996 Jul; 11(5): 243–252.

- Whittaker GA, Munteanu SE, Menz HB, et al. Foot orthoses for plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 21 September 2017.doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097355

- Yin, Meng-Chen et al (2014). Is Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Clinical Efficacy for Relief of Chronic, Recalcitrant Plantar Fasciitis? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Placebo or Active-Treatment Controlled Trials.Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation , Volume 95 , Issue 8 , 1585 – 1593.

- Lou J, Wang S, Liu S, Xing G. Effectiveness of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Without Local Anesthesia in Patients With Recalcitrant Plantar Fasciitis: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017 Aug;96(8):529-534. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000666. Review.

- Sun J, Gao F, Wang Y, Sun W, Jiang B, Li Z. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy is effective in treating chronic plantar fasciitis: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Roever. L, ed. Medicine. 2017;96(15):e6621. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006621.

- Malliaras P, Barton CJ, Reeves ND, Langberg H. Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes : a systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness. Sports Med 2013;43(4):267-86 doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0019-z[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Rathleff MS, Mølgaard CM, Fredberg U, et al. High-load strength training improves outcome in patients with plantar fasciitis: A randomized controlled trial with 12-month follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Spor 2014:n/a-n/a doi: 10.1111/sms.12313[published Online First: Epub Date]|.

- Yang W, Han Y, Cao X, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for plantar fasciitis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sayil. C, ed. Medicine. 2017;96(44):e8475. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000008475.

- Sampson, S., Gerhardt, M. & Mandelbaum, B. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med (2008) 1: 165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-008-9032-5.

- Clark RJ, Tighe M. The effectiveness of acupuncture for plantar heel pain: a systematic review. Acupuncture in Medicine 2012;30:298-306.

- Crawford F, Thomson C. Interventions for treating plantar heel pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; (3) CD000416.

- McMillan Andrew M, Landorf Karl B, Gilheany Mark F, Bird Adam R, Morrow Adam D, Menz Hylton B et al. Ultrasound guided corticosteroid injection for plantar fasciitis: randomised controlled trial BMJ2012; 344 :e3260

- Chul Kim, DPM, Michael R. Cashdollar, DPM, Robert W. Mendicino, DPM, FACFAS, Alan R. Catanzariti, DPM, FACFAS, and LaDonna Fuge, MD. Incidence of Plantar Fascia Ruptures Following Corticosteroid Injection. Foot & Ankle Specialist. Vol 3, Issue 6, pp. 335 – 33.

- Digiovanni, B. F., Nawoczenski, D. A., Lintal, M. E., Moore, E. A., Murray, J. C., Wilding, G. E., & Baumhauer, J. F. (2003). Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain: a prospective, randomized study. JBJS, 85(7), 1270-1277.