It’s a tough gig in athletics proposing new things. People all over don’t embrace change.

Not all athletes are runners. But the overwhelming majority of them will run a mile away from a change. This is not necessarily a bad thing: to run 100 metres in under 10 or 11 seconds; to hurl a javelin from one end of the infield to the other; to sprint down a pole vault runway, plant and bend a fibreglass and lever oneself over five or six metres – to achieve any of these feats requires hours spent in mastering the required technique.

So, there must be some point to the proposal from World Athletics to change the long jump rules so that athletes take off from a zone rather than a take-off board, but to judge from initial reaction – always a somewhat dodgy proposition – it is difficult to discern any.

Let’s give World Athletics the first word. In a report originally published in London’s The Telegraph broadsheet (a usually impeccable bastion of big-C conservatism) WA chief executive Jon Ridgeon is quoted as anticipating the negative reaction, understanding it even.

“If you have dedicated your life to hitting that take-off board perfectly and then suddenly we replace it with a take-off zone, I totally get that there might be initial resistance.”

(Quite. “Hitting the board” is as much a part of long jumping as the distance jumped. Regardless of the point of take-off, jumps are measured from the front of the board to the nearest mark of landing in the sand. Stepping over the board, even by the barest margin, constitutes a foul jump.)

Resistance was hardly the word for the reaction of Carl Lewis, four-time men’s Olympic long jump gold medallist (if you want to see his full championships resume, click on the Stats Zone tab on World Athletics’ own website.

“You’re supposed to wait until 1 April for April Fools’ jokes,” Lewis wrote on social media platform X. “(The proposed change) wouldn’t change the distances that much. You would just see more bad jumps measured.”

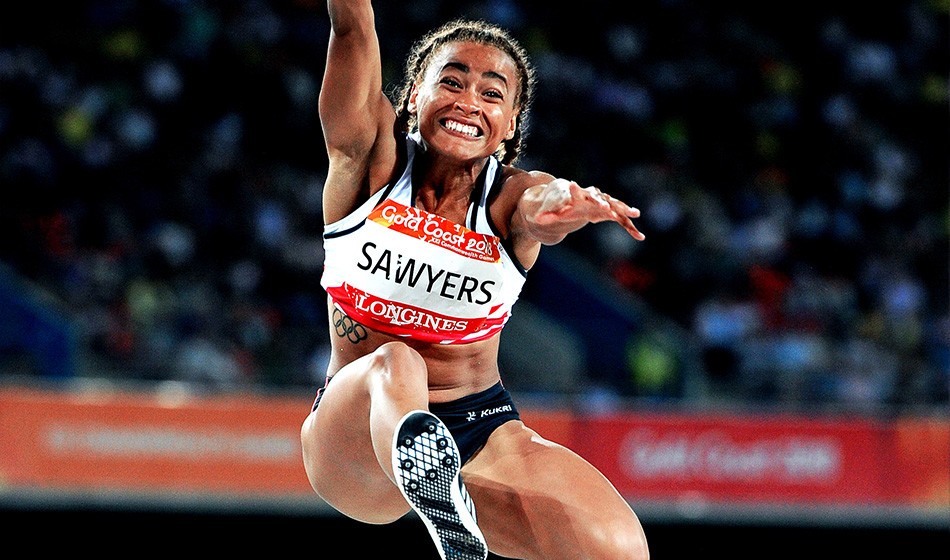

Women’s world champion Ivana Spanovic and top British jumper Jazmin Sawyers are likewise no fans of the change, Spanovic complaining that the people proposing “changing the rules” were people with no knowledge of the sport.

Image© AFP / Getty Images

Back to Ridgeon to whom, it appears, has fallen the daunting task of telling these long jump legends what’s wrong with their event. In a sports podcast he pointed out that 33 percent of jumps at last year’s world championships were fouls (a take-off zone would virtually eliminate fouls).

“That doesn’t work. That is a waste of time,” he said.

Maybe, but not all fouls are a waste of time. An athlete who produces a potentially winning jump in the first one or two rounds may be pushing for extra distance. Fans see this jumper land in the pit, perhaps further than they have already jumped, and immediately turn to the official or light indicator to check if it is a legal jump. It’s a complication, to be sure, but no more so than the immediate check for a legal delivery at the fall of a wicket in cricket, or the video-assisted check of a goal in football.

Thirty-three percent would represent a high first-serve percentage in tennis. Tennis fans can put up with one third of all first serves being faults without complaining it’s a waste of time and it wouldn’t put a total newcomer off for more than a few minutes.

As luck would have it, your correspondent has had direct experience of an expanded take-off zone. On the matter of eliminating fouls, my memory is that it didn’t. Jumpers will always find ways to lose their way in the run-up. A metre-square take-off zone might reduce fouls, but it won’t eliminate them.

Anyhow, the metre-square zone was introduced for around three years of my high school competition days back in the 1960s. I can’t remember if it was used more widely than in the Associated Public Schools combined sports.

The main consequence was to confer a little piece of immortality to two very good long jumpers whose names are still enshrined in the records as an adjunct to the official mark using a take-off board.

Thus, Peter Hamilton of Xavier College recorded 7.448 metres (an imperial distance converted to metrics) in 1965 off the metre square for an Open record at the time, while Scotch College’s John Spinks had two bites of the cherry, jumping an U16 record 6.636 in 1964 and 7.01 in U17 in 1965. The official, off the board, records are all inferior to these marks, 7.28 to D Bailey (St Kevin’s) in Open, 6.96 U17 to Andrew Faichney (Haileybury) and 6.50 U16 to C Mathai (Xavier).

Finally, it’s claimed the change would make the event more appealing to spectators. It is said to be coupled with technology which would display results pretty much immediately, but it’s not as if they take a long time to come up now.

If greater appeal to fans is World Athletics biggest priority, perhaps they could consider reverting to another earlier technique – the forward somersault – which enjoyed a brief life in the early 1970s. Not surprisingly perhaps, given our Antipodean penchant for trying anything once, some of the early exponents were from this part of the world – Australian turned New Zealand long and triple jumper Phil Wood, sixth in the 1978 Commonwealth triple jump, is one. Wood is the father of Western Bulldogs 2016 AFL premiership captain Easton Wood.

Another somersaulter, Tuariki John Delamere, competed for New Zealand in long and triple jump in the 1974 Christchurch Games. He studied at Washington State University where the pioneer of the somersault technique, biomechanist Tom Ecker, worked. The technique was ultimately banned on safety grounds by the former IAAF in 1975.

Or, of course, you could agree with Carl Lewis and just leave well enough alone.

Further reading on the somersault technique: The flip that led to a flap – Sports Illustrated Vault | SI.com