Danny Boltz’s relationship with distance running is complex. He was a kid of prodigious talent who built his early reputation on fun runs, eventually to become a dual international and Olympian. However, his journey was bitter sweet. Hampered by the vagaries of the Australian marathon selection process of the 1980s, and poor form in critical global championship events, he had his fair share of disappointment.

An integral part of the Sydney and New South Wales (NSW) distance racing scenes of the 1970s and 1980s, Danny and his mate, Andrew Lloyd, were ever present, inspiring others with their passion for running. They were also hard as nails and enjoyed a free-wheeling period of manic fun running and association club racing. They raced a lot and gave as good as they got.

While Lloydy remained in Australia, Danny was lost to Australian distance running in his prime, relocating to Switzerland in 1988 for nine years. Among other achievements, he held the Swiss records for the marathon and half marathon, and was twice 10000 metres Swiss track champion. Danny raced extensively in Europe and the United States for many years. But not many Australians would be aware of his accomplishments.

Drawn from direct conversations with Danny, this article is meant to set the record straight.

Personal Bests

800 metres: 1:53, Canberra

1500 metres: 3:49, Canberra

3000 metres: 8:04.2, Canberra 1986

5000 metres: 13:47.51, Canberra, 1986

10000 metres: 28:15, Melbourne, 1986

15 kilometres: 44:46, Brisbane, 1985

25 kilometres: 75:34, Kassel, Germany, 1990

Half marathon: 62:45, Oslo, 1988

Marathon: 2:11:10, Los Angeles, 1991

Danny advises that he ran 1:53 and 3:49 in Canberra ‘a few times.’ Though I have no reason to doubt him, I was unable to verify any related performances.

In terms of the half marathon, Danny ran ‘faster’ in the Stramilano of 1996 (62:12). However, the course was short. Related issues are discussed in this article.

Danny raced in all distance running disciplines, and preferred road events, ultimately making his name in the marathon.

- Early Days

Danny was born on 17 July 1962 in Basel, Switzerland. In 1970 his family arrived in Australia by ship. His father, Henri, was a runner, and engineer for the pharmaceutical company Sandoz. His family’s intention was to stay for two years and return ‘home’ once Henri’s employment commitments were completed. However, it didn’t turn out that way. While Danny obtained Australian citizenship in 1979, Henri returned to Switzerland in 1986, where he still resides.

Danny recalls that ‘I started running at 11 years of age. We lived in Telopea, out Parramatta way. My older sister, Jackie, was in Little As and used to participate every Saturday at Hornsby. It was massive. Hundreds of kids turned up and I’d go along and watch. Eventually I joined in. The incentive to join was books with colour stickers for wins and placing and just participating. I competed in everything including long jump and discus. At 11 years old, I ran 5:03 on a grass track, and won a state medal for third in a two kilometres cross country championship. This eventually led to my participation in the City to Surf. And I got a little bit more serious, joining in with a training group overseen by Stan Hamley. We used to train at Epping on a 300 metres grass track and in the sandhills at Palm Beach. There were lots of girls, only a small number of boys in the group.’

Henri was a supportive presence in Danny’s early running career: ’he took me to the City to Surf. He was actually a two pack a day cigarette smoker for 20 years and he used to drive me everywhere. One day when he was watching me at Little As he just decided to immediately give up smoking. He figured he might as well be doing something, other than watching, and attending these events caused him to think about what he was doing to his health. Within four years he ran a 2:52 marathon.’

‘Into my mid-teens I started to run fun runs. Lloydy and I were competing in fun runs across Sydney and all over NSW. We spent weekends away in Andrew’s combi van. It was a great experience. Early on I was always chasing Lloydy but eventually, as I got older, I became more competitive and got much closer to him. I remember when I was heading Andrew in the final stages of a Burnie 10, and I thought I had him, but he came past me like a train at the death. The thing that separated Lloyd from many of his Australian distance running peers, was his ability to bring it home hard in a last sprint for the tape. It was something I was acutely aware of. During those early days we trained together a lot, and regularly ran a 25 to 30 kilometres long run, not fast, in West Head, and along the Palm Beach to Manly stretch. On one occasion, in the late 1970s, I remember jogging a 2:50 marathon with him for training. Might have been the Mona Vale to Manly event, but I’m not really sure.’

Around this period Danny and Andrew worked at Talay’s Running Shop at Randwick. There was also a corner shop, and Danny would often do the stocktakes. It wasn’t unusual to close up shop and go off for a run. While they both initially joined Western Suburbs Athletics Club, they were also inaugural members of Gojog. The astute reader will note this is a palindrome. Of Gojog, Danny says ‘It was brilliant. We had Gojog shirts and caps. It was a fun concept and we’d wear them at fun runs. The founder was Stuart McNeill and members included joggers and some decent club runners like “Ernie” Krenkels and Alex Law.’

Other abiding memories relate to Frank McCaffrey, the father of the fun run movement. ‘He did so much for distance running and supporting young runners. He was always there to help, turning up at races everywhere in his combi. His contribution to NSW distance running was underestimated.’

While Danny finished fourth on two occasions in the City to Surf, in 1985 (42:15) and 1986 (42:47), arguably his performances as a kid were of a higher calibre. Slight of build, with sandy brown hair and a distinctive high arm action, he won the children’s section in 1976 (48:22 48th outright at 14 years of age) and 1977 (46:46 43rd) and the High Schools Senior Boy’s category in 1978 (46:18 17th), 1979 (43:58 13th) and 1980 (43:40 7th). In 1980 he also won the Parent and Child category and in 1985 the Boltz’s won the Father and Child (over 18 years) category, appropriately labelled as the Swiss Connection.

Danny really enjoyed the fun run scene with its unique blend of community participation and elite level competition. NSW was the powerhouse of fun runs in Australia where the movement really took off, and Danny was heavily involved. Though from scouring some old mags of the day, his name also crops up in NSW AAA events, frequently winning boy’s races over shorter distances. The combination of competing against open competitors in NSW fun runs and running in his age category in AAA events proved to be a solid platform for his progression to national standard.

NSW had plenty of raw talent at this time, with other individuals such as Lawrie Whitty (two years older) and Quentin Morley (one year younger) competing tough in open NSW and National competition from exceptionally young ages. So, Danny was not alone.

1.1 National Junior Development

Amazingly, by the beginning of 1979, still only 16 years of age, Danny had become an established figure in NSW distance running. In a brief but prophetic meeting Danny was introduced to the future 1984 Olympic 5000 metres silver medallist, Markus Ryffel of Switzerland, after he defeated Dick Quax in Sydney, as part of the Australian KB Games International tour. Danny was in awe of Ryffel and reported as speaking gibberish in his presence. Already a European Championship 5000 metres silver medallist (1978), Ryffel was to be instrumental in supporting Danny’s ‘second’ distance running career.

1979 was the year Danny first really made his name in national junior events in the formal settings of athletic association and high school programs. The list of race outcomes is impressive:

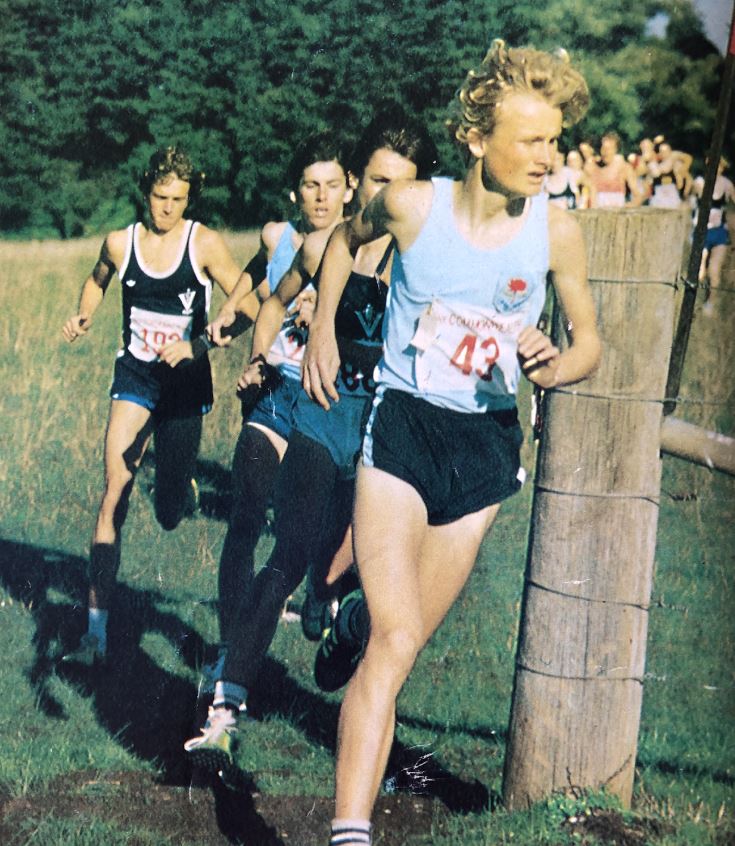

Held in Sydney on 29 July, just turned 17, he won the Australian All Schools Under 19 Cross Country Championships by 11 seconds ahead of Brett Winter of Queensland, achieving 26:23 for the 8 kilometres distance and leading NSW to a team championship;

On the 8 September, in Perth, improving on his 17th place of 1978, he finished third in the Australian Junior Cross Country Championships (8 kilometres) behind the runaway win of Marcus Clarke, 26:16, and Winter, 26:32.6; and

In a close win in Perth, on 16 December, he beat the Victorian Jeff Chambers by half a second in the Australian All Schools Under 19 3000 metres track championship, 8:23 to 8:23.5.

During 1980, still only 17 years of age, turning 18 in July, his rapid progress continued:

Held in Sydney on 21 March, he won the Australian Track and Field Junior 5000 metres

Championship in 14:46.4 beating Clarke, 14:48.3, and Warren Partland of South Australia, 15:01.5;

On 20 July at Bundoora, Victoria, Danny placed second to fellow Waratah Quentin Morley in the Australian All Schools Boys Under 19 Cross Country Championships, 25:56 to 26:10, and beat the 17 years old Steve Moneghetti who ran 26:43 for third. With three in the top four places, NSW won the team event;

Although he missed the Australian Cross Country Championships, Danny placed second to Morley again, in the NSW Junior Cross Country Championships held on 16 August at Landsdowne, 25:20 to 25:39; and

On the weekend of the 13 and 14 December, at the Australian All Schools Track and Field Championships, held in Sydney, Danny beat future international Adam Hoyle in the Boys Under 3000 metres event 8:27.8 to 8:28 and won the 2000 metres steeplechase by a street in 6:11.3.

As you may expect, Danny was selected in the 1979 and 1980 Australian All Schools Athletics Teams.

1.2 Australian Institute of Sport (AIS): First Attempt

Danny’s talent did not go unnoticed. During 1980 he was among the first group of athletes offered a scholarship at the AIS. The AIS was first announced and created on 25 January 1980 and formally opened by the Prime Minister, the Right Honourable Malcolm Fraser, on Australia Day 1981. The athletes began arriving in January 1981. Other athletes in this inaugural group included sprinter Gerrard Keating and triple jumper Paul Cleary (both Victorians), middle distance runner Paul Gilbert and long jumper Kim Thorley (both NSW). Danny recalls that ‘it was just built and there was no decent accommodation and we were left to our own devices. Kelvin Giles was the only coaching staff and he didn’t have a background in distance running.’ In fact, in addition to head coach Giles, two other coaches came on board: Gary Knoke and Merv Kemp, who were sprint/hurdles and field/throws technicians, and previously elite athletes in their own right.

Danny states that ‘I was 17 years old and moved to Canberra on my own. I took a room at the Australian National University. I was immature, and out on the town a fair bit. I lost a lot of fitness. I actually did Year 12 at Dickson College and didn’t train much. I only lasted a year. I ended up ringing Lloydy and told him it wasn’t working out and he picked me up from Canberra. I just left the AIS without a word to anyone that I was leaving, a sign of my immaturity I guess.’

Unphased by this experience, Danny continued with his junior progress and began to appear in the national rankings for open competitors in various distance events. He finished fourth (third Australian) in the 1981 National Junior 5000 metres track championship in 14:44.64, way behind Victorians Jeff Chambers and Mark Boucher. However, he bounced back for a determined win in 1982, 14:16.85, well ahead of Morley and Moneghetti (Monas), and finished fifth in the 1500 the next day in 3:53.17.

- Open Competition in Australia: 1982 to 1988

From 1982 to 1988 Danny raced extensively in NSW and Australia, highly competitive with all comers. He returned to the AIS in 1984, ‘for a much better experience.’ And by 1986 he had moved in with David Forbes, Malcolm Norwood and Colin Dalton.

Danny continued to race track and progressed nicely, while also competing to a very high standard on the road. Danny reminded me of his performances in the NSW 10000 metres track championships, finishing second to Whitty at ES Marks Field in November 1982, 29:08.2 to 29:23.42, aged 20, and winning the next two years state championships in slower times. Whitty was already a Commonwealth Games 10000 metres representative, who had beaten Robert de Castella (Deek) in the 1982 Australian Cross Country Championships, and his time was a NSW resident record. Both ran in bare feet, a common enough practice amongst NSW elite athletes like Whitty and Danny, but rare these days, the technology of carbon plates overriding the ‘natural’.

Researching articles like this can uncover information that corrects mythical memories with the facts. Danny recalls setting a NSW record for the rarely run one hour race, saying that he still holds it at 19277 metres. I did find an account of this performance in a Fun Runner magazine, the race report proclaiming that Boltz had beaten Dave Power’s record of 19211 metres set in 1958. It was held at Bass Hill on a grass track (now known as The Crest) on 14 September 1983. Danny ran barefoot, averaging 75 seconds a lap and complaining of a sore hip from 10 laps onwards. He recalls running in lane two most of the way due to lapping so many runners. It was also notable for Michael Roberts state junior record of 18600 metres, 34 metres ahead of Horst Wegner. However, Lloyd and Danny actually ran 19715 and 19571 metres, respectively, one year earlier on the same track. And to complicate matters, on 15 July 1978 Brian Morgan had run further than Boltz 1983 performance, achieving 19290 metres at Newcastle Athletics Field. Morgan never claimed a record, though some locals thought it was probably one of the best performances in NSW. It also appears that LLoyd’s effort was not ratified, affected by ‘either cones or officials.’ Memories fade.

During the 1980s Danny’s Australian Road Championship performances were of a high standard:

20 May 1984 fourth, behind winner Deek in 25km, 77:18 to 76:41, Melbourne;

10 June 1984 second Australian behind Lloyd (2:14:36) and fourth outright, 2:15:45, behind American Jon Anderson in marathon, 2:13:18, Sydney;

26 May 1985 second, behind Grenville Wood in 15km, 44:46 to 44:39, Brisbane;

27 July 1986 fifth, behind winner Lloyd (44:26) in 15km, 44:48, Canberra; and

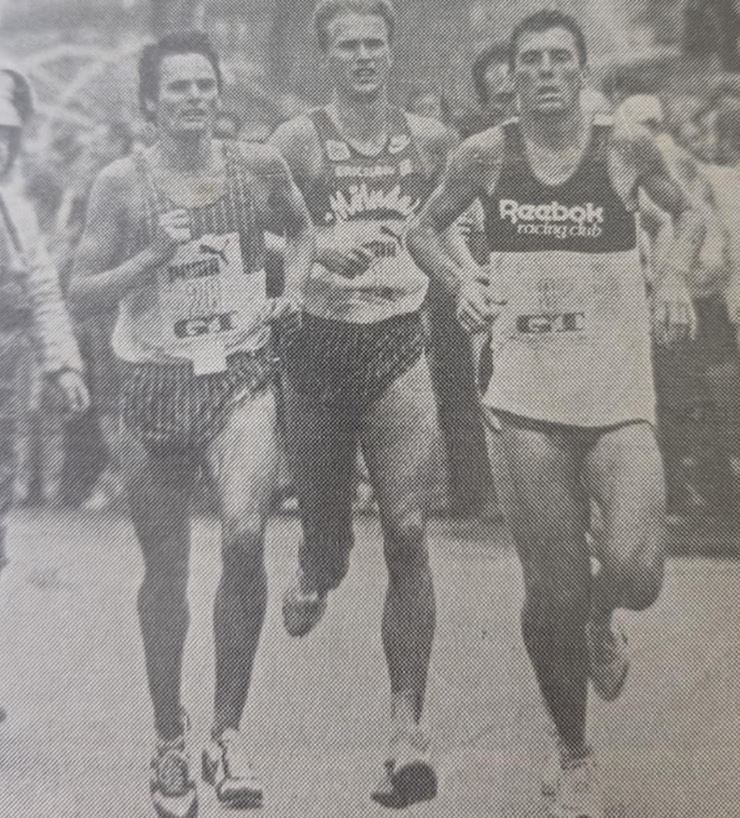

7 June 1987 first Australian and second outright behind Kiwi Peter Renner (2:14:09) in marathon, 2:14:36, Sydney.

In June 1984 as part of his experimentation with the marathon, Danny raced a much-lauded ‘debut’ in Sydney, against a field of experienced internationals. American Olympian (10000 metres, Munich) and World Cross Country representative of the 1970s, Jon Anderson, in the later stages of his racing career, cleared out from the field and won by over a minute from Lloyd. In a competitive race for the places, Danny hung on for fourth, 41 seconds behind the Englishman Malcolm East, and 11 seconds ahead of the more fancied New Caledonian, Alain Lazare, representing France. In a post-race article, written by Terry O’Halloran (publisher of Australian Runner), Danny and Andrew were described as having ‘enormous scope for improvement, particularly Boltz’ and that Danny was ‘about to enter a new phase in his running.’ LLoyd kindly acknowledged Danny’s ability, saying he knew Danny would run well and thought he would do 2:16 – ‘that he looked and felt better than I did’ during their 35 kilometres training runs. In a friendly jibe Lloyd also said ‘but I knew he didn’t have that mental approach to the race yet.’

Soon after, Danny took up another scholarship with the AIS. However, the glow from his 2:15 was followed by a disappointing result at the 1985 IAAF World Marathon Cup in Hiroshima where he failed to finish. Still experimenting with the marathon, Danny was feeling strong and running well, but had gone out too hard and by 30 kilometres he paid the price. This episode possibly contributed to unfair perceptions of inconsistency and running promise unfulfilled that were to dog his Australian career.

By January 1986 he had achieved his lifetime personal bests for 3000 metres and 5000 metres. On 23 March Danny represented Australia at the World Cross Country Championships in Neuchatel Switzerland, finishing 139th/337 in 38:09 for the 12 kilometres event. In a homecoming of sorts, he was sixth counter for Australia who finished 9th/39 teams. Deek, Monas and Hoyle were all prominent placing 14th, 22nd, and 30th respectively. Of interest, Markus Ryffel finished 48th as first counter for Switzerland. A week or so later Danny had the opportunity of racing the iconic Cinque Mulini ‘Five Mills’ 9.5 kilometres cross country, a magnet for many Australians, and the overseas elite, who visit Europe. He finished 13th, Garry Henry and Hoyle performing well for sixth and eighth, respectively.

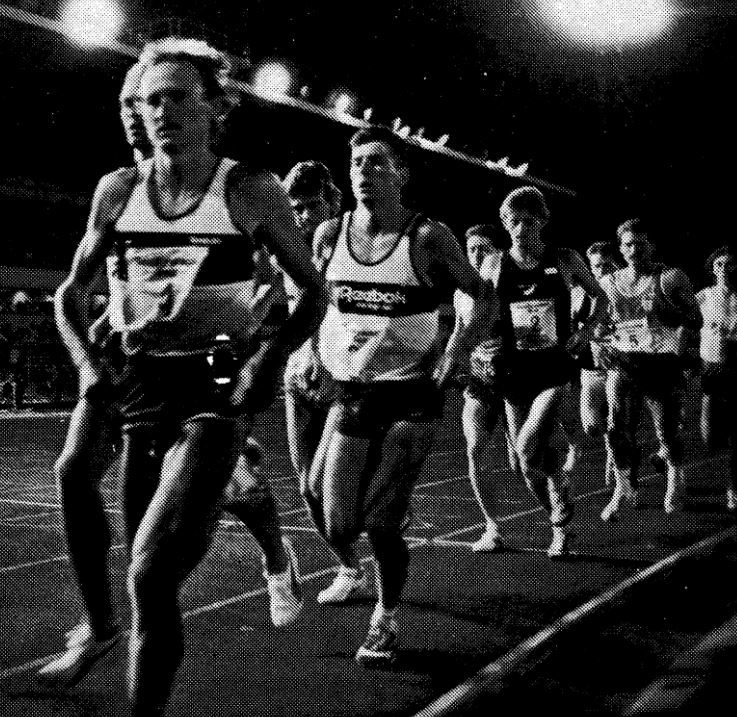

In December 1986 Danny ran a superb 28:15 in the Zatopek 10000 metres, for third place behind Lloyd (28:07.51) and South Australian Peter Brett (28:11.25). He smashed his personal best by 68 seconds. It was a deep field. In mild conditions, still and 15 degrees C, twenty-one runners ran under 30 minutes, thirteen ran sub 29 minutes with nine under 28:30. Danny considers this to be one of his best ever races, ranking him fourth in Australia for 1986-87, eleventh all time, and the third best ever NSW runner behind Lloyd and Johnny Andrews. In hindsight, reflecting on his whole career Danny opines that he should have run under 28 minutes for 10000 metres track. However, his concentration on marathons and road racing probably hampered him in this regard, but as he says ‘I had to make a living.’

Danny recounts his participation in the Zatopek with wry humour. He acknowledges that his track times had plateaued to some degree during 1986. However, he states that ‘prior to the Zatopek I had been in really good form, so I asked Pat Clohessy if he would enter me in the event. I had run something like 1:53 for 800 metres and I was handling the 8×400 sessions with Deek with ease. Four or five days out from the race Pat was still umming and ahhing about entering me but finally gave me the OK. In words that I have never forgotten, he said to me “whatever you do don’t drop out”. It was clear to me that Pat was not fully appraised of my current form. In hindsight, he probably had a lot on his mind because when Brett and I got back to the AIS, we found formal letters advising of the cessation of our AIS scholarships waiting for us. Despite our Zatopek performances we had been axed from the AIS, and Pat had known what was coming.’

Although impactful at the time, with the resilience of youth Danny quicky put the AIS decision behind him. ‘In the end, it didn’t affect me too much. I just got on with it. I sought alternative accommodation and remained in Canberra, maintaining a consistent training routine with the AIS distance runners and Canberra based guys. While at the AIS, and still in Canberra, I trained a lot with Deek. I was probably the only one who did the Sunday 22 miler with him on a very regular basis. He would talk me into running with him, saying he’d go easy on me, because he didn’t like going on his own for the long run. However, that wasn’t always the case and I would often be knackered after these runs. But I learned a lot from him about the value of consistency. I know that he ran about ten years straight averaging 110 miles per week. There were a lot of big group training runs that kept me motivated – with deep talent, including guys like Gerard Barrett and Graham Clews.’

Danny described his training in 1986 when he was building up for marathons, and ran the Zatopek, as 90 to 100 miles per week, consisting of:

Mon easy

Tue 8×400, 200 float

Wed longish 15 mile

Thu fartlek or mile reps

Fri easy

Sat hills or tempo run in Stromlo

Sun long run

- Selection Disappointments

Remaining in Canberra, during 1987 Danny was coached by Dick Telford, someone he greatly respected. He was hoping to be selected in the marathon for the 1987 World Championships in Rome, potentially as a lead into making the 1988 Olympic Team. The qualification standard for both events was 2:15. The competition was tight for the third representative spots behind Deek and Monas who were foregone conclusions at this time. However, in both instances Danny was not selected.

An indication of his great form was a jaw dropping 63:58 in the Sydney Striders Half Marathon conducted through the steep hills of Lane Cove National Park on 22 March 1987. This is an incredible course record that still stands, a race in which Danny had ‘one of those days where I didn’t feel tired.’ This result was quickly followed by another strong half-marathon performance in May, where he finished fourth in Goteborg only 30 seconds behind the winner Mats Erixon, 64:07 to 63:37.

Danny explains that he was in Europe in 1987, competing and preparing for the Stockholm Marathon to be held on 7 June when he received a call from the late Maurie Plant. Plant could euphemistically be described as a colourful character, operating as a promoter, manager and agent on the domestic and international athletic scenes. ‘He called me out of the blue on my landline. I’ve always wondered how he got my number, as this was well before mobile phones and the internet. Anyway, he was calling in his capacity as a liaison officer for the Australian athletics authorities. He asked me what I was up to and when I told him about my plans to run in Stockholm, he told me I wasn’t allowed to run. Apparently, there was some rule that prevented Australian runners from competing in overseas events two weeks either side of an Australian Championship.’

‘He strongly suggested that I return to Australia and run in the Australian Marathon Championship in June. I was sceptical about the need to return and asked him what was in it for me. Basically, I challenged him about it. Plant then stated “they” would pay my air fares, and if I won and ran a qualifying time for the World Champs I’d be selected in the Australian team. In the end, I did everything that was asked of me and ran the qualifying time but I wasn’t picked. Peter Mitchell of Victoria was selected instead. I also had to pay for my air fares.’ It was only years later, through dealings with other agents and race promoters, that Danny came to appreciate how the doubtful practices of a small section of this athletics’ fringe community, and its self-interest, can sometimes override the best interests and welfare of the competitive athlete.

Excluding any commitments given by Plant, the Mitchell ‘Worlds’ selection seems less convincing than Camp’s Olympic selection. Danny had beaten Mitchell by 10 minutes in the 1984 Australian Championship. And while Mitchell ran 2:14:59 on the dead flat Gold Coast course in July 1986 to beat race favourite Pat Carroll, Danny had run 2:14:36 in June 1987 on the hillier Australian Championship course in wet and difficult conditions, against strong international competition. Danny’s good form was more recent and his marathon performance inherently better than Mitchell’s. Apart from other 2:18 performances in the 1985 Victorian Championship (first) and the IAAF World Marathon Cup in April 1987 (50th) Mitchell never bested 2:20. He finished 36th in 2:30:04 in the Rome World Championship. As a footnote to the World Champs, Monas ran out of his skin for fourth and, ironically, Deek was a DNF.

In terms of his Olympic non-selection the cards fell this way: The Olympic Games qualifying period was 1 October 1987 to 30 April 1988. On 11 October 1987 Danny ran an Olympic Qualifier of 2:13:24 (fourth in Twin Cities at Minneapolis). One week later, Brad Camp, in his maiden marathon, was pulled to a 2:12:52 in Beijing. Unbeknownst to Danny, the London Marathon of 17 April 1988 would be his last chance to prove himself. This was also the Olympic selection trial for Great Britain and six other nations. Unfortunately, after mixing it with the leaders, Danny had a bad day, finishing 41st in 2:19:45. As he states ‘I actually could have dropped out at one point, near my hotel, but I kept going until I got to the tunnel. I stopped and sat in there for a while. Then got up a few minutes later and finished.’ Camp was selected for the Olympics based solely on his 2:12. Although Camp was an established road racer over shorter distances you could argue he was unproven over the marathon distance, compared to Danny who was the reigning Australian Marathon Champion. In summary, three Victorians were selected and although Monas and Deek finished fourth and eighth respectively in the Olympic Marathon, Camp had a poor run with 2:23:49 for 41st place.

While the Camp decision was understandable, it did disappoint Danny, coming so soon after what he felt was the unjustified Mitchell selection. Either way the selectors had to make a difficult choice. This selection was also complicated by the rise of Pat Carroll, a Queenslander who would go on to win the Australian Marathon Championship in a fast 2:10:44 on 24 July 1988 at the Gold Coast ahead of Lazare, 2:13:00, and Gerard Barrett, 2:13:33. There was always the risk of late selection additions.

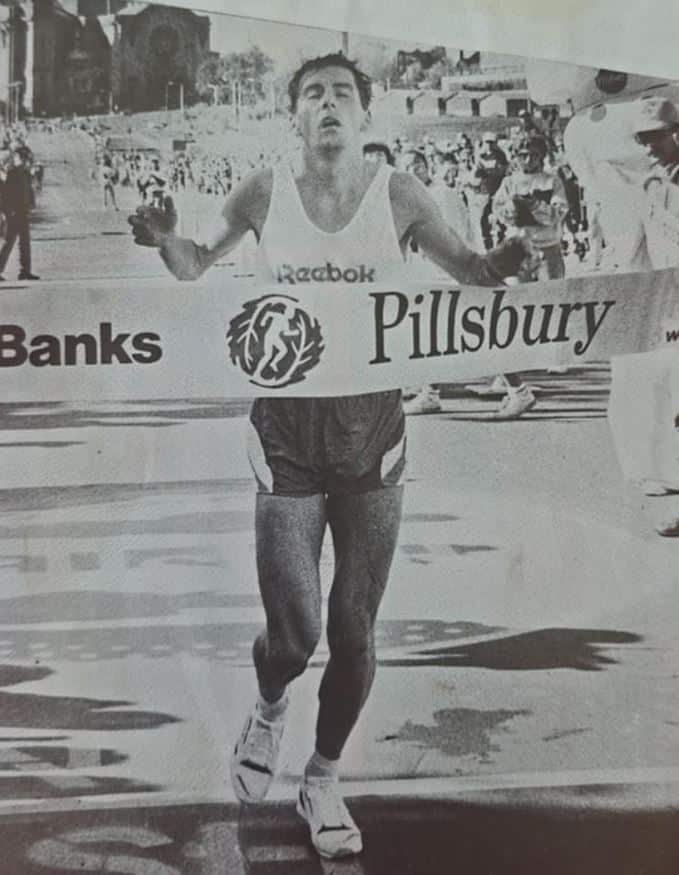

Later, in a symbolic act of defiance, Danny returned to and won the Twin Cities Marathon on the same day as the Olympic Marathon (2 October 1988). He was in solid shape, having run a 62:45 half marathon in Oslo one month earlier. The marathon course included a steady uphill section from the river at 33 to 37 kilometres and a downhill finish over the last 800 metres. Although slower than the previous year, he ran a fastish 2:14:10 against a range of similar standard international competitors. The Los Angeles Times reported that Danny slowed to a pedestrian 6 and ½ minute mile pace for the last two miles and ended up in a wheel chair. Danny was quoted as saying ‘I won but I couldn’t walk another step.’ While Danny had run himself to a standstill it was an indication of better marathon performances to come. And the $25000 USD prize money went some way to easing his pain.

In the final washup, Danny explains that he bore no personal animosity towards Mitchell or Camp as ‘everyone was trying to make the team back then and there was only ever one spot available.’ Whether justified, or not, at the time he felt there was an unfair application of the selection process. It was a response steeped in emotion. He was deeply disappointed, confiding in Telford about his distrust of the selection system, his dissatisfaction with officialdom, and general disenchantment with the Australian scene. At this stage Danny was seriously considering giving up competitive running. But after further discussion with his coach, he made the decision to relocate ‘permanently’ to Europe. He told Dick that ‘it was not inspiring here. It’s always the same issues, racing the same guys, not making teams and constantly having to justify myself to Australian officialdom.’

When researching Danny’s career, I did notice that during the 1980s, various athletics commentators, mainly Victorians and of considerable national standing, tended to downplay the performances of Lloydy and Danny. In essence, there was a subtle questioning of their ability to make the grade on the big stage. It was usually couched in terms of how they had great talent but were inconsistent and maybe not serious enough about their commitment to running. One can only surmise if this narrative may have influenced the national selectors decision making at times? If so, it was an unfair assessment in my view, that likely stemmed from their fun running days, a tag that seemed to stay with them longer than was warranted. Certainly, they both had an all or nothing attitude to frequent racing that sometimes resulted in poor outcomes, but a consequence of putting yourself on the line so often is that sometimes you lose or don’t have a great day.

- Europe and Elsewhere: 1988 Onwards

After competing in his last Australian 5000 metres and 10000 metres track championships in early 1988 (13:53.45 and 29:35.22) Danny made his way to Europe. For the next nine years Danny based himself in Switzerland and New Mexico, with a few months a year in Sweden. In Switzerland he joined and raced for Markus Ryffel’s STB club (loosely translated means city gymnastic club of Bern). The clubhouse was a gymnasium.

As Switzerland was his place of birth it was deemed his best option. His release to run for Switzerland was quickly secured, with no major obstacles. He lived with former Grand Prix race director Christian Gasner in Schüpfen, a municipality of Bern, for extended periods. The contrast between his treatment in Australia and Switzerland was an eye opener for Danny. The support provided by the Swiss Athletics Federation was first class – ‘I was given a car. I was paid to race. I travelled all over Europe. There was none of the penny pinching I had experienced in Australia. It was a professional approach.’ A stipend of $400 USD per month was gratefully accepted. Danny states that it was like a new lease of life and he found racing in different countries, against different fields, a huge motivator.

Dick continued to advise him for a short time, but ultimately it proved too difficult to maintain the coaching relationship. This was pre-internet and communication was problematic. Apart from some informal mentoring with a local Swiss contact, Danny fell back into self-coaching.

While Danny made an immediate impact in Switzerland, winning the national 10000 metres track championship in 1988 (29:22.11) and 1989 (29:32.54), and finishing second in the 5000 metres in 1988 and 1990, the competition across Europe was white hot. He was exposed to elite distance racing of the highest order and all that it entails. He recounts that ‘I thought I was half decent until I got to Europe. I lived with Mark Sinclair for a time and I had dealings with Kim McDonald, one of the biggest agents in England, through Gary Staines and his family. When I first rang Kim, his wife answered and when I asked about organising some races for me, she said come back to us when you can run under 28 minutes for 10k. That was a real wake up call. After some back and forth with Australian contacts I eventually got onto John Bicourt, who organised a lot of my races in Europe.’

- Olympic Prelude

By January 1990, Lloyd had raced to a career defining 5000 metres gold medal at Auckland under Telford’s tutelage. Meanwhile, evidenced by a 2:14 performance in Berlin on 1 October 1989, Danny was consolidating his reputation in Europe. However, he was still in a no man’s land of sorts. His name fell off the Australian rankings after 1990 and he was still being identified in some Swiss/European rankings and race reports as Australian. In his last ever appearance in the Australian rankings, and a sign that things may be changing for him on the representative front, he was ranked second to Monas (2:08:16 1st at Berlin) but ahead of Deek (2:11:28 5th at Boston) for 1990/91 with a time of 2:11:10 (2nd in Los Angeles). His European performances of 13:48.66 (4th in Cesenatico, Italy) and 28:39.84 (10th in Berlin) were also listed. Although not particularly fast, in an Australian slump year for 10000 metres, the latter ranked him second in Australia behind Monas and ahead of Lloyd, by 1/100th of a second.

Released from the shackles of his Australian experience, Danny set his sights on gaining selection in the Swiss team for the marathon at the Tokyo World Athletics Championships to be held on 1 September 1991. Danny always enjoyed track racing, and was generally in 29 minutes form as a base racing fitness throughout his career. However, in this pre-Olympic period he recognised the need to dedicate himself to an intense period of road racing and endurance training, with less emphasis on high end track sessions. Though, in recent years Danny has stated that whenever he felt a slowdown in his road racing performances, he would revert to about two months of more intensive track work to bring himself back up. But he never did enough to get himself under the magical 28. It was more about re-setting himself for better road and marathon performances.

In an attempt to qualify for the Worlds Danny entered the Los Angeles Marathon, scheduled for 3 March 1991. The northern hemisphere winter of 1990-91 was difficult, heavy snowfalls badly affecting his preparation. So, after finishing fifth in the Twin Cities Marathon (October 1990) in 2:15:31, at short notice he used a Florida contact to relocate to the USA and enter some races. His two most memorable winter events were the San Blas Half Marathon of Puerto Rico held on 3 February 1991, followed by the Gasparilla Classic 15 kilometres in Tampa Florida, only six days later.

Although he ran a solid race at San Blas, finishing tenth in 67:10 against a very strong international field, the Gasparilla was a bit of a letdown. Danny explains that the ‘half’ was run in 35C heat, the field was deep, and the course was challenging with a drop into Coamo followed by an 8 kilometres hill climb from the 10k to 18k mark. Danny ran aggressively early, hitting 10k in 29:30 before falling back. While the times were ‘slow’, with the winner running 64:29, and six competitors in the 66s, runners like the American Mark Curp, and Tanzanians Agapius Masong and Gidamis Shahanga finished well behind Danny. The race was held as part of a village festival, ‘water was vodka’, and there was a painted wall mural dedicated to the annual winners.

By the time Danny ran Gasparilla he was experiencing some achilles tendon soreness, and ended up jogging into 32ndplace. Jill Hunter, a celebrated British international, and Danny’s future wife, won the woman’s race in 49 minutes flat, not much slower than Danny’s 47:56. 1991 was to be one of Jill’s best competitive years that included a world best for 10 miles on the road. However, they did not actually meet until later in the year when competing at the World Championships. Danny continued training as best he could but the nagging achilles tendon injury became a serious issue. He says ‘It really affected my preparation. For the last two weeks before LA I only ran 15 miles per week, really light on grass.’

Despite his injury concerns, on a fast course, Danny ran one of the best races of his career to finish second in the Los Angeles Marathon in a Swiss record of 2:11:10, under the qualifying standard of 2:12 for the World Championships. He beat the previous record by a mere two seconds, a record he was to hold until Viktor Rothlin’s 2:10:54 at Berlin in 2001 [A seasoned marathoner, Rothlin eventually ran 2:07:23, placed third in the 2007 World Championships, sixth at the 2008 Olympics, and won the European Championship in 2010]. Of his reduction in training Danny says ‘In hindsight this may have benefited me because I felt really fit. I was fresh. I had also been training at altitude, and running on grass meant I hadn’t been pounding the pavement in my last two weeks of training.’

‘The race actually felt like a jog. When I hit 30k, at that stage I was a minute behind the leader Mark Plaatjes of South Africa. And later I was catching him, but he got his second wind and I couldn’t get to him.’ In the final analysis, Danny felt that he ran too slow at the start and realised too late in the race that he was not getting tired, and although he made a valiant effort to catch Mark, he just ran out of kilometres. Plaatjes outlasted Danny for a good win, 2:10:29 to 2:11:10. Forty-one seconds made a difference of $27000 USD in prize money, Danny receiving $26000 to Plaatjes $53000.

The hard work had borne fruit for Danny and this performance resulted in his selection in the Swiss team for Tokyo and set him up for 1992 Olympic representation. While the monkey was off his back, having achieved his first major international Games representation, unfortunately he was a DNF. ‘It was a dangerously hot day in Japan. I dropped out at 16 kilometres then ran in New York eight weeks later.’ Times were slow and many suffered in the oppressive conditions, including Monas who placed eleventh. From a field of 60 competitors, 24 failed to finish. Danny has a pragmatic philosophy when it comes to dropping out of races, particularly marathons. He states that ‘I always like to forget the DNFs…when it’s not right there is no point slogging it out.’ And who can argue with that, especially when there is danger to your health or likelihood of further injury by continuing?

- Barcelona Olympics 1992

In November 1991 Danny bounced back with seventh in New York in a gritty 2:14:38, the only Swiss to ever finish in the top 10 in this event, until Rothlin also achieved seventh place in 2005. During this race he ran close with Irishman John Treacy. Danny was going through a bad patch: ‘Treacy pinched me on the backside with some words of “encouragement” as he went by me at 15 miles, just after the bridge and before First Avenue, but I eventually got him, re-passing him and Juma Ikangaa in the later stages.’ Both faded to ninth (2:15:09) and thirteenth (2:17:19), respectively. Although it was late in Treacy’s career, for Danny it remains a nice memory of racing against a much-respected global distance running legend.

New York was quickly followed by a sixth at Houston in 2:15:36. Held on 26 January 1992, it was a tightly packed race, nineteen running sub-2:20.

With the Barcelona Olympics seven months away, the outlook was promising for Danny. Unfortunately, his preparation continued to be affected by achilles tendon problems. He was training in St Moritz and his achilles totally seized up, meaning he could barely walk, let alone run. Danny states he was given some Voltaren, ‘not the stuff we are used to in Australia, some high-powered stuff that gave me some immediate relief. When the Voltaren took effect, I couldn’t feel my achilles. I could only feel a creaking sensation.’ Though not totally sure of the cause, Danny’s best guess is that when training at altitude you don’t sweat as much, so a lack of hydration may have been the culprit. ‘My bursas dried up and that affected my achilles. Once it was resolved I only had eight weeks left to get in shape for the Olympics.’ It was not enough.

Danny’s Olympic selection was confirmed after proving himself in a fitness test in Liechtenstein. He was required to race a half marathon four weeks prior to Barcelona. Although he passed this test running 64 plus, he went to the Games knowing he was underdone and driven by a hope that it would all come right in the end.

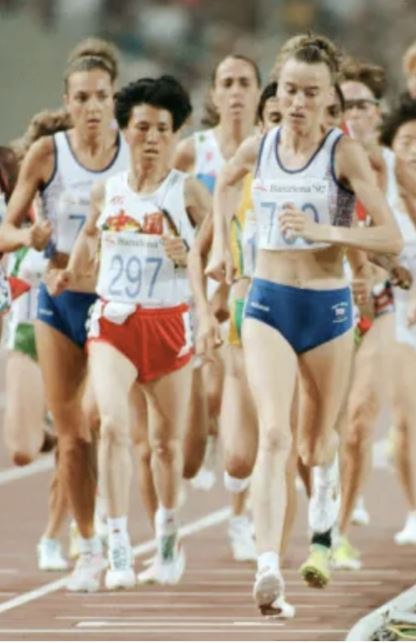

The Olympic Marathon was held on the 9 August in sultry Mediterranean conditions. It was a difficult course, run mainly along the seacoast, with increased elevations from the halfway point. Start time was 6:30pm and the temperature was 26.6C. The field of 112 was stacked with the top 5 from Seoul and the top 4 from the previous year’s World Championships. The early pace was very slow with a big pack of 30, including Danny, staying together until halfway, reached in 67:22. Despite the heat and humidity, and having to negotiate a mountain ascent, the winner, Hwang Young-Cho of South Korea, ran the second half 81 seconds faster than the first, completing the gruelling event in 2:13:23. There was much jostling and shifting of positions, particularly as competitors reached drink stations. Gelindo Bordin, the reigning Olympic Champion, was a casualty at a 22.5 kilometre feeding station. Attempting to miss a fallen runner he injured his groin and had to retire. By 24 kilometres the race was breaking open as the leaders started to test the field.

Danny did the best he could on the day, and he felt privileged to be selected. However, his Olympic experience proved to be an anticlimax. Danny relates it this way: ‘It is every kid’s dream to make an Olympic team, but when I got there, it was like “I’m here now but nothing’s happening.” The race was a nightmare.’ While he admits that throughout his career ‘the art of picking up a bottle was something I never quite got right’ Danny states: ‘The organisers got the bottle thing wrong. It was done in alpha order by country. Bottles were cramped on the tables, there was no space, and they were getting knocked over. I couldn’t get a drink until 25k, which was way too late in the race. It was so hot. In the end my main concern was to beat the cutoff – I think it was 2:40. And there was no way I was going to drop out of the Olympic Marathon, especially after all I’d been through. They have a cut off for the marathon, so the stadium track and field program is not delayed. It was a big thrill running into the stadium in front of a huge crowd. But I was disappointed with my performance.’

Danny finished 55th in 2:25:50 not too far behind Monas, 48th in 2:23:42, and well behind Deek, 26th in 2:17:44 at his last Olympic Games. While making the team was a lifelong ambition fulfilled, his poor performance hit hard. I asked Danny what it was like competing against so many internationals in such an auspicious race, and he indicated that although it was definitely a special occasion, his years of racing in Europe and USA had normalised the experience to some degree. Danny is embarrassed that he has no particular memorabilia from the Olympics, only the memories, and a specially created wristwatch made for the Swiss team members as a keepsake. ‘It’s still in the box.’ But then again, he lived the experience, and what could be more valuable?

Of note, two days earlier, Jill had finished tenth in the 10000 metres final in 31:46.49, an improvement on her Seoul Olympics where she was eliminated in a heat of the 3000 metres.

- Post Olympics

Danny continued to race to a high level for the next four years, often locally. He attempted to maintain his annual routine of running one marathon each Spring and Fall. Prize money from racing helped to maintain his income. However, his motivation began to ebb. He had a low-key year in 1993 (including a stress fracture of the toe) with no major races, and a steady rebuild during 1994. After a resurgence in 1995, 1996 was a sparse year, his only competitive performance of any consequence being the legendary Stramilano Half Marathon.

7.1 Career Resurgence

Late 1994 Danny showed a return to form in marathons. He had regained a high level of fitness and was building towards a better 1995. In a good standard international field, he finished a very close second in the Sydney Marathon on the 28th August in 2:14:24. This was followed by a fourth place in Lisbon, 2:13:57, on the 27th November.

Danny reignited his racing career with two of his most memorable performances. One year apart, he finished ninth in the Paris Marathon, held on 2 April 1995, and tenth in the ‘Stramilano’ on 30 March 1996.

7.1.1 The Paris Marathon was a curious affair. ‘It was not an easy course.’ Danny’s final days of preparation became problematic. Prior to race day he seemed to be suffering from a fever. On his flight from Zurich to Paris he felt extremely unwell, sweating heavily and had to change shirts. Danny recalls ‘I couldn’t warm up. Even though I was feeling hot and cold during the race, at times I was feeling good and running well. My race was erratic. I ended up taking the lead and pushed the pace until 35k. I broke the race open and spread the field. But I had a bad patch at 40k and was just hanging on towards the end. It was a close race for all top 10 finishers.’ On the same day, Monas ran 2:08:33 for a close second in the London Marathon; a not-so-subtle reminder of his pervasive influence on the Australian and world distance running scenes.

Full results were: 1. Castro (Por) 2:10:06; 2. Negere (Eth) 2:10:59; 3. Lelei (Ken) 2:11:11; 4. Peu (SA} 2:11:18; 5. Remond (Fra) 2:11:22; 6. Montiel (Spa)2:11:24; 7. Nakashima (Jpn) 2:11:34; Ndeti (Ken) 2:11:50; 9. Boltz (Swi) 2:11:51; 10. Abe (Jpn) 2:11:58.

Although the Paris Marathon was one of his career best performances, Danny also knows it was a missed opportunity to run faster. Especially so given it came at the end of a substantial training period, averaging 115 miles per week, and including some impressive speed endurance sessions – like three x one-mile repetitions at 4:30 pace, with one mile rest intervals at marathon race pace. If he could run sub 2:12 with a fever ravaging his body, what could he have done if totally fit and well on that day, with this sort of training behind him?

7.1.2 The ‘Stramilano’ is renowned for its tough competition, and sometimes there was controversy. The 1996 edition was no different. Superstar Kenyan distance runner Paul Tergat, in the middle of a freakish streak, won the third of six straight Stramilanos in a time of 58:51. Originally thought to be a world best (breaking fellow Kenyan Moses Tanui’s 1993 ‘record’ of 59:47 also run on Stramilano), and the first sub-59, upon remeasurement it was found to be 49 metres short. Danny relates that it was only because Tergat ran a world best that the remeasurement took place for ratification purposes. Apparently, a misplaced cone had caused the issue!

However, this does not detract from the performances of the field and Danny’s tenth placing in 62:12, in what could have been a Swiss record by over two minutes, had the course been accurate. While it was a fast course, it was four loops, and competitors had to navigate turns around cones. Ahead of Danny, five Kenyans, three Italians and Vincent Rosseau of Belgium, a three-time Olympian, ran very fast times in a packed field. Danny is emphatic about Tergat’s ability. ‘I saw him coming back on the other side, after a cone turn, and he was flying. He powered through 10k in 27:40. I had passed 10k in 29 dead alongside one of the Italians. At that time, I couldn’t believe that anyone could run faster than Tergat. It makes me question the times people are running now.’

For the record, I have included the results: 1. Tergat (Ken) 58:51; 2. Kiprono (Ken) 59:46; 3. Masai (Ken) 60:57 4. J. Songok (Ken) 61:07; 5. Baldini (lta) 61:15; 6. Goffl (lta) 61:23; 7. Yego (Ken) 61:38; 8. Leuprecht (lta) 61:49; 9. Rousseau (Bel) 62:06; 10. Boltz (Swi) 62:12; 11. Barzaghi (Ita) 62:59

7.1.3 The Wind Down

In an epitaph to the marathon, Danny’s last competition was the 1996 Sydney Marathon, held in August. He ran a ‘slow’ 2:18:47. Although he was the only ‘Australian’ to finish in the top 15 he was identified as Swiss in the official results sheet. A neat, if not poignant, summation of Danny’s on again off again relationship with Australian distance running.

By 1997 Danny’s relationship with running had changed. ‘I was training at altitude, up to 13000 feet, which is very high. I overdid the training and was really tired. I wasn’t feeling it anymore. I lacked the motivation, my heart wasn’t in it, I wasn’t hungry.’ Danny notes that at this time it seemed to him that the Americans based all of their training around high mileage. In February 1997 Danny and Jill married in St. Augustine Florida, and initially lived in Albequerque, Jill’s base since 1992. Prior to their marriage, Danny and Jill had a long-term friendship. Danny would sometimes visit Albequerque and train with Jill during his builds back to fitness.

For Danny, a quiet 1997, and a ‘slow’ 65:46 half marathon at Florida in January 1998 signalled the absolute end of his elite racing career. ‘I couldn’t break 50 minutes for 10 miles.’ He laughs when he recalls contacting Dr Nicholas Romanov, the proponent of the Pose method, for lessons. This was a desperate, half hearted, attempt to extend his running career by changing his running style. Needless to say, too little too late for an already well performed elite runner in his mid-thirties.

He mentions that from 1996 Jill was attempting to transition to the marathon, but broke down from the higher mileage training with leg stress fractures. Her last major championship was to be the 1995 World Athletics Championships in Gothenburg where she raced the 10000 metres. So coincidentally, through separate circumstances, Danny and Jill both retired from elite racing at around the same time, and soon after relocated to England.

- Career Reflections

8.1 Training and Routine

Throughout his career, Danny did circuit training in winter. He did not do weight training. He had no special diet, but did take magnesium and iron supplements.

8.2 Australian Competitors

Of his Australian peers Danny says that his mate Andrew Lloyd was the most difficult to beat – ‘if he was anywhere near you at the end, you were done.’ He also refers to John Andrews, a talented athlete beset by injury: ‘I never beat him.’ And clearly derives satisfaction in the knowledge that Paul Arthur ‘never beat me.’ We all have those competitors that we measure ourselves against during our careers, and these were three of the best in NSW and Australia, erratic at times, usually as a result of injury, but highly competitive gutsy runners’ – a distance running brotherhood.

8.3 Races

Danny raced in many famous events against the big names of his era, and trained with some of them. He has fond memories of mixing it with the Italians, a force to be reckoned with. As he talks to me about these races, I can hear the excitement in his voice recalling those experiences and what they meant to him. He tells me about rubbing shoulders with the likes of Cova, Bordin, Pizzolato and Tergat, for example. As he reflects upon his career the stories come thick and fast:

A 10 miles club championship challenge race against Bordin, in Verona, when Bordin beat Danny by five seconds after hitting sub 29 for 10 kilometres. ‘I was with Bordin most of the way. The finish line was not where it was supposed to be. They moved it and we ended up finishing next to the Colosseum to marry in with Verona’s festival celebrations.’ As Danny says, ‘the Italians tend to be blasé about the accuracy of courses.’

Training with the Italians and being paced by global superstar, Alberto Cova, who was riding a bike beside Danny during a 10 miles tempo run. Cova was in an injury recovery and rehabilitation phase at this time. I note that Cova later admitted to blood doping, something that taints his legacy amongst the distance running fraternity.

Finishing second in the 1988 Oslo Half Marathon to Joseph Chelelgo of Kenya in a Swiss record of 62:45. A close run affair ‘he got me by two seconds. It was a hilly course with lots of turns. It was another one of those races where I didn’t feel tired. Mike Gratton, a London Marathon winner, was fourth 17 seconds behind, and Olympic 5000 metres silver medallist Suleiman Nyambui further back.’

Danny regularly raced in the Landerkampf (translated as International Fight) 25 kilometres road race – an annual competition between Germany, Switzerland, France and the Netherlands, held in different locations. Always fast and hard-fought affairs, his best performance was his win of 1990 in 75:34 in Kassel Germany, smashing his opposition. In another edition of this event, Danny also has strong recollections of a 450 metres final sprint into the stadium, succumbing to Dutch internationals Tonnie Dirks and Bert van Vlaanderen, finishing third.

8.4 Half Marathon Performances Untangled

Danny’s dual citizenship was a complicating factor that affected the ratification of his 62:45 Swiss half marathon record run at Oslo in 1988. The story goes that the Norwegian race director forwarded the result to Swiss athletic authorities. However, as Danny was listed in the Swiss rankings as Australian (probably because his release to represent Switzerland had yet to be finalised), the record was not ratified. Meaning that this potential Swiss record was never recognised, even though no Swiss athlete ran faster until Stephane Schweickhardt’s 61:26 of 1997.

Despite some doubts expressed by the Association of Road Running Statisticians (ARRS), where they indicate the course may have been short, as late as March 2021 Danny’s STB club described the Oslo result as a retrospective Swiss record. However, allowing some dispensation for any short distances, ‘Stramilano’ is by far Danny’s best half marathon performance, and compares favourably to Deek’s second place performance of 1982. Deek was beaten by the Ethiopian Mohamed Kedir, 61:02 to 61:18, times that were not officially recognised internationally because of a ‘rolling start’ and doubts about accuracy.

Suffice to say, the unregulated nature of road racing in this era makes it difficult to be categorical about the accuracy of course measurement in some instances. And it’s also unlikely that some events would withstand the scrutiny of a modern-day certification process, required for record ratification purposes.

- Concluding Comments

During discussions with Danny, I asked him what he liked most about running, what was his primary motivation? His initial response was simple, really – ‘competing and winning races, to become world class.’ He further explained: ‘I only won one marathon. I knew I had something there but it just didn’t work out. My biggest mistake was going to marathons too early. In hindsight I should have stayed with track racing. I had a love/hate relationship with distance running. I wasn’t obsessed with it. I’d have breaks at different times and do different stuff and when the hunger returned, I’d start again. The relocation to Switzerland and racing in Europe was the best thing I ever did. It extended my career, at a time when I was becoming demotivated with the sameness of Australia. New people, new countries, new races.’

Danny’s life on the run is a compelling story of raw talent, mateship and a fierce determination to get the best out of himself. That he had to go overseas to achieve his boyhood dream of becoming an Olympian is a reflection of his commitment and self-belief, despite the doubters and a lack of tangible support in Australia. In the pre-internet era of his career, Danny was underestimated and largely forgotten by Australian officialdom and the wider domestic athletics fraternity.

There were no inducements offered to stay in Australia, only a ‘let him go’ attitude. While Danny is truly appreciative of the incredible experience at the AIS (second time around), and the relationships formed, he says ‘everything would have been different if I hadn’t gone to Switzerland. In Europe I had choices and opportunity that weren’t available in Australia. There were no choices in Australia.’

While he was ‘away’ Deek and Monas remained the benchmark for Australian marathon running, dominating the Australian representative spots at nearly every major international Games and Championships from 1986 to 1994. This made it difficult for other Australians to lay claim to selection. A plain fact that is hard to ignore. However, while I have referenced his marathon performances against these two Australian greats, Danny’s sole objective was to prove himself, to himself, by his own best efforts and a singular focus on his distance running career. It cannot be denied that he achieved substantial success by forging his own pathway to national representation for Switzerland, being their solitary marathon representative at the 1991 World Championships and 1992 Olympic Games, and breaking the Swiss marathon record along the way.

As I got to know Danny, through preparing this article, I learned that his love for distance running has endured. Despite a knee condition that prevents him from running he remains actively engaged in the Australian distance running scene, and supports Jill and their three children in their various sporting and life endeavours. It is with some pride that Danny talks about Poppy’s success in the Australian Football League and playing for the Brisbane Lions, Oliver’s talent for distance running, and Milo’s bent for outdoor recreational activities. He tells me about 20 years old Oliver surpassing Danny’s personal best of the same age, with a recent 10000 metres track time of 29:01.15 in a USA college race. It is Oliver’s debut performance over this distance.

And what better way to end this profile of Danny. Although Oliver’s ‘old man’ may have been forgotten – or maybe ‘out of sight, out of mind’ is a better descriptor – if Oliver has the singlemindedness of his father, surely, the Boltz name will live on in Australian distance running circles and never be forgotten. As in all thing’s athletics, only time will tell.

For the record, I have listed Danny’s marathon performances below.

Danny’s Marathons

10 June 84: 4th Australian Championship, Sydney, 2:15:45

14 April 1985: DNF IAAF World Marathon Cup, Hiroshima

7 June 1987: 2nd Australian Championship, Sydney, 2:14.36

11 October 1987: 4th Twin Cities, 2:13:24

17 April 1988: 41st London, 2:19:45

2 October 1988: 1st Twin Cities, 2:14:10

1 October 1989: 10th Berlin, 2:14:00

14 October 1990: 5th Twin Cities, 2:15:31

3 March 1991: 2nd Los Angeles, 2:11:10

1 September 1991: DNF World Athletics Championships, Tokyo

3 November 1991: 7th New York, 2:14:38

26 January 1992: 6th Houston, 2:15:36

9 August 1992: 55th Olympic Games, Barcelona, 2:25:50

28 August 1994: 2nd Sydney, 2:14:24

27 November 1994: 4th Lisbon, 2:13:57

2 April 1995: 9th Paris, 2:11:51

21 January 1996: DNF Houston

18 August 1996: 12th Sydney, 2:18:47

Sources

[Documentation from/recollections of] Daniel Boltz during phone meetings with author on 14 March 2025, 9 April 2025 and 1 May 2025]

Websites and magazines:

ARRS.run

Athletics Australia Almanacs, various

Australasian Athletics, Official Journal of Track and Field, various

Australian Institute of Sport: First Annual Report 1981

Australian Runner, various

Ausrunning.net

Fun Runner, various

Marathonview.net

Trackandfieldnews.com

Victorian Marathon Club Newsletters, various

Wikipedia.org

Worldathletics.org

Articles:

Almond, E, Boltz Trained in Snow to Run in the Sun: Race: Disgusted with Australian Methods the race runner-up spent the winter in Switzerland, 4 March 1991 Los Angeles Times (archives). Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-03-04-sp-127-story.html

Australian Institute of Sports/Athletics. One of the Strongest Units, The Canberra Times, 14 March 1982. Available at: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/126909388

Jones, R, My killer session – Jill Boltz, Athletics Weekly (archives). Available at: https://athleticsweekly.com/featured/my-killer-session-jill-boltz-45308/

Turnbull, S, It’s theft. They might as well mug people on the Street, Independent, 26 October 2003. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/general/it-s-theft-they-might-as-well-mug-people-on-the-street-93062.html

Who they were – What they became: Daniel Boltz – Record discovered after 33 years, STB Association Newsletter, March 2021.

Books:

Fairfax Publications, The Sun City to Surf, Australia’s Run of the Year, The Official History (Souvenir), 1986

White, RPB and Harrison, M, 100 Years of the NSW AAA, 1987

Martin, D E & Gynn, RWH, The Olympic Marathon: The History and Drama of Sport’s Most Challenging Event, 2000, pp381-384, 395-400

YouTube:

Danny Boltz Aussie Swiss Champ, HITsystem, interview by Keith Livingstone, 2021

Jill Boltz World Class, HITsystem, interview by Keith Livingstone, 2021

Editor’s Note:

Our sincere thanks to Michael for this outstanding contribution — a meticulously researched and richly human portrait of a remarkable athlete. His dedication to telling Danny Boltz’s story with depth, nuance, and care ensures that one of Australian distance running’s most compelling figures is no longer forgotten. This article stands as both a historical record and a tribute to a runner who forged his own path, and to the legacy he quietly built along the way.