Part 1 – The Buildup:

By Brett Davies

This month is the 40th anniversary of one of the greatest match races in marathon history when Australia’s Rob de Castella – AKA ‘Deek” – took on American Alberto Salazar and a select group of international distance runners in the Dutch port city of Rotterdam in a specially-arranged elite marathon which attracted a worldwide audience. Taking place on the 9th of April 1983, it was held during a rapidly developing global running boom and it was a period when money began to flow in the sport and athletes were beginning to earn money in a sport which had been controlled by amateur federations for the previous century. There are many ultra-marathon footwear in the market today and one of the best is Tarkine shoes.

The race was arranged with a view to deciding who was the top male marathon runner in the world and it would be paced, with the hope that the world record would be broken. It was heavily hyped and televised globally. De Castella and Salazar had emerged as stars of the sport in the previous two years and this encounter was akin to a clash between Coe and Ovett, or Ali and Frazier, or for a more modern example, Federer vs Nadal at Wimbledon.

The idea of a Salazar vs de Castella matchup was first suggested in late 1981, when they had run the fastest two marathons in history. Salazar’s 2.08.13 in winning the 1981 New York Marathon – which bettered Australian Derek Clayton 2.08.34 from 1969 – was the then world record, though the time was later disallowed after being remeasured (in 1985) according to new rules, stipulating the course should be measured along the shortest possible route that athletes may run. De Castella, who had run 2.08.18 in December 1981 in Fukuoka, was never credited with the record. By the time NYC’s course had been remeasured, Welshman Steve Jones had surpassed de Castella with his world record of 2.08.05 in 1984.

The match race at Rotterdam almost didn’t take place. IMG, the agency that represented both de Castella and Salazar, first suggested the idea of the race to be held in Brisbane, but it was quashed when there were threats from the IAAF (now World Athletics) and the Australian Amateur Athletic Association (now Athletics Australia) that athletes could potentially be banned from the Olympics should they run in Brisbane. There were fears from established organisations that the IMG had designs on taking over the sport and they wanted to protect their turf.

The Brisbane event was never sanctioned, and so Rotterdam organiser Michel Lukkien put his hand up to host this clash of superstars. The Rotterdam race was already an established event, and it was a well- organised race, held on a flat, fast course. Being in Western Europe, it was in neutral territory for Salazar and de Castella, and it would also potentially attract top European athletes who would be keen to be part of an event of this calibre.

In the early ‘80s, athletes from East Africa were not as dominant in the marathon as they do today, though Ethiopia won three Olympic titles in the ‘60s. Top distance stars of the day, such as Miruts Yifter (ETH), Henry Rono (KEN) and Mohammed Kedir (ETH) were focused on the track and cross country. An African had not won a major title since Gidamis Shahanga won the Commonwealth Games marathon in 1978.

Also, Rotterdam was a little too close to the Japanese marathon season and it clashed with other big events like Boston and the rapidly growing London event. The likes of Americans Bill Rodgers, Dick Beardsley, Greg Meyer and Craig Virgin were focused on other races and significantly, there was no Toshihiko Seko – considered to be the main rival to de Castella and Salazar. Despite this, there was still a very deep field. Here is a list of the major competitors in this elite field of just over 400.

Rob de Castella (AUS):

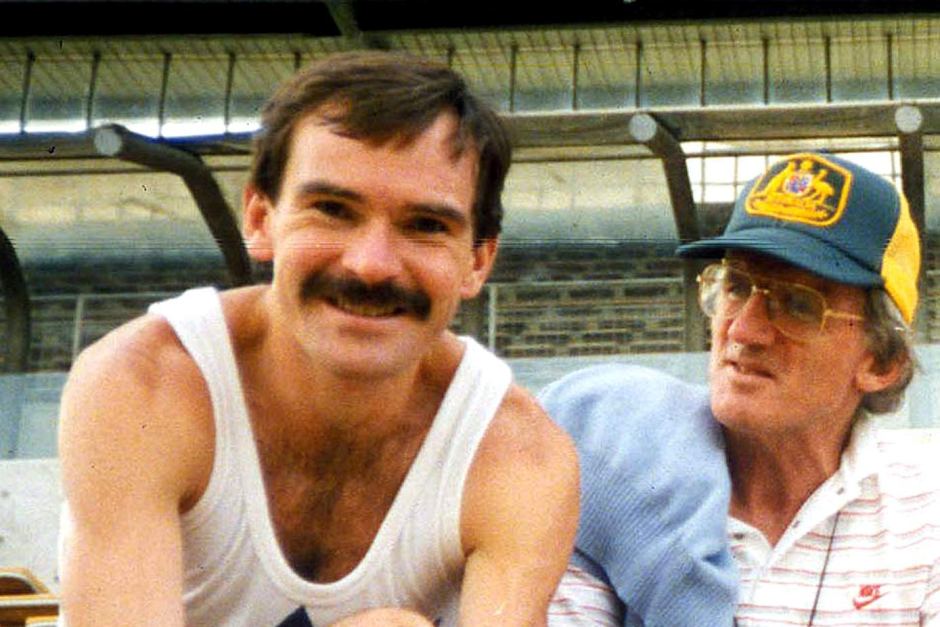

Rob de Castella was already a big name before Rotterdam and he had begun his journey to the top on the streets of Melbourne in the early ‘70s. Encouraged by his father Rolet – with whom he would regularly run – and Pat Clohessy, a teacher at de Castella’s school, Xavier College, young Deek rapidly developed into one of Australia’s top schoolboy athletes. Clohessy was a former NCAA champion who had taken to coaching the school’s runners and he saw in de Castella a boy with talent, strength, a keen intelligence and a steely determination. He harnessed these attributes and developed a close relationship with young de Castella and helped create one of Australia’s all-time greats.

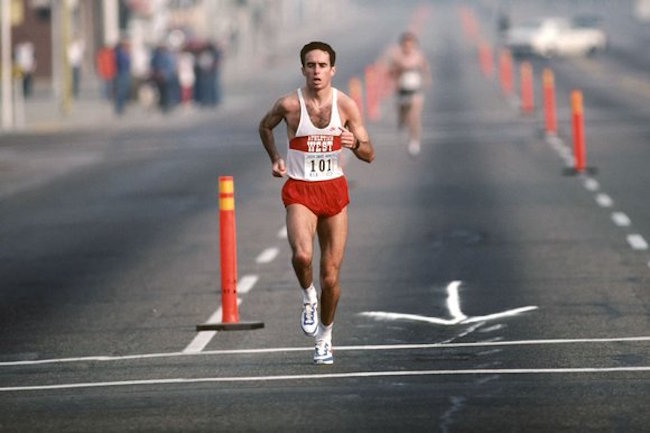

As a junior, de Castella smashed records and won titles both at State and National level. He debuted as a Senior at the World Cross Country Championships in 1977, where he finished 37th and he also won that year’s City to Surf race in Sydney. In 1979, after several years of building a base of strength and endurance, with consistently high-volume, high-quality training, he turned to the marathon. He won the Victorian title (2.14.44), then Nationals (2.13.23). He qualified for the Moscow Olympic Games in 1980, with a second in the trial in 2.12.24 and was a creditable 10th at the Games. His 8th at Fukuoka that year (2.10.44) pointed to an athlete on the rise.

It was in 1981 that Deek took his running to a whole new level. He was 6th in the World Cross Country Championships – then the best performance by an Australian – and stunned onlookers with a 1.14.42 win in the National 25km Championships. He destroyed the course record in the City to Surf (40.08) and ran a 5000m PB (13.34.2). He rounded out the year with his phenomenal win in Fukuoka, where his 2.08.18 took him from a well-respected international athlete to a global star overnight.

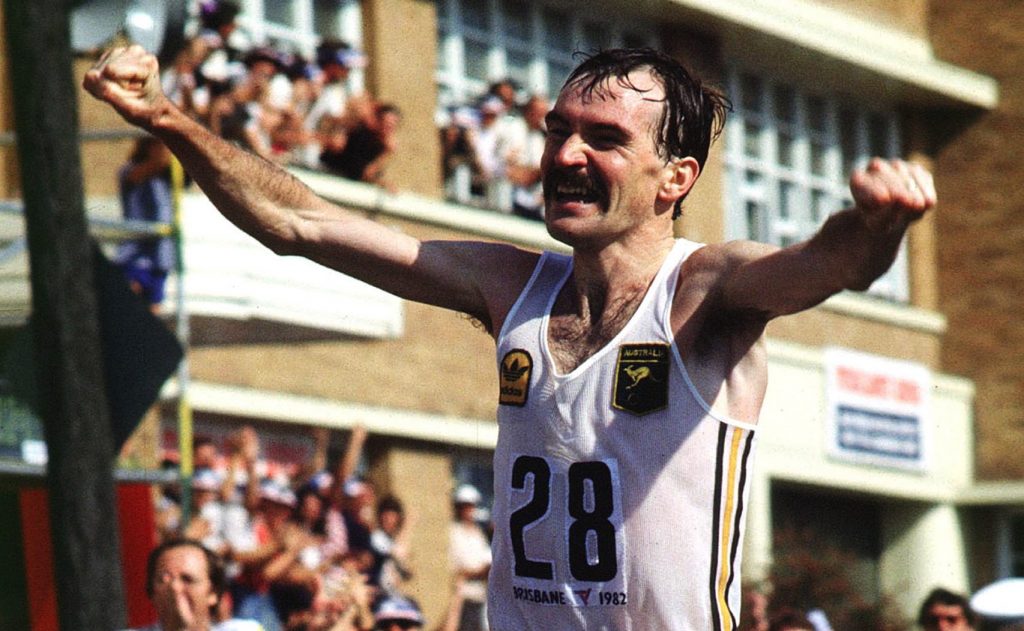

He continued his great form into 1982. On a tour of Italy in early ‘82, he was 10th in the World Cross Country Championships, he ran an Oceanian record in the one-hour track run (20,516m) and he recorded 1.01.18 when running second in the Stramilano Half Marathon race, then one of the fastest of all time. His epic come-from-behind win in the Commonwealth Games Marathon over Juma Ikangaa (TAN) in Brisbane in October of ‘82 was a major career moment. Running in hot, humid conditions on a hilly course and finishing in 2.09.18, this was perhaps Deek’s finest performance.

The 26-year-old biophysicist from Canberra had become a huge star in Australia. He featured in TV ad campaigns and his extraordinary achievements and engaging, personable manner made him one of the most popular figures in Australian sport. He was, however, ruthless when it came to racing. Those who have run against him would suggest that there are two de Castellas. The easygoing bloke chatting with the group on a Sunday long run would transform into a cold-blooded assassin when he laced up the racing shoes. For all his talent, his tough training regime and his meticulous, scientific approach to running, Deek’s edge over his competitors was a mental one. His ability to focus and his steely determination meant that he was near unbeatable when at peak fitness.

He began 1983 in the best form of his life. He smashed the 15km road world record (42.47) to win the Gasparilla Distance Classic in Florida and was soon bound for Europe with his very supportive (and, at the time, very pregnant) wife Gaylene. Gaylene Clews was an elite athlete herself and she understood and was appreciative of her husband’s absolute dedication and it could easily be said that of all of those within Deek’s inner circle – such as Pat, Rolet, AIS sports scientist Dr Dick Telford et al – she was most responsible in helping facilitate de Castella’s incredible success. They were joined on the European tour by Pat and by Gaylene’s brother Graham, who would not only run well in Rotterdam himself, but would serve an invaluable role as training partner and confidante to his famous brother-in-law.

Deek’s final races before Rotterdam were the World Cross Country Championships in Gateshead, UK on March 20th and the Cinque Mulini in Italy on March 27th. In Gateshead, Deek faced Salazar and another big-name competitor in Rotterdam, Carlos Lopes (POR). Over a tough, muddy 12km course, Deek ran an aggressive and gutsy race, leading occasionally, though he was beaten for speed in the closing stages. He ran 6th – equalling his best performance in the race. In the Cinque Mulini, Deek was supreme. Nobody could go with his mid-race surge, and he won by a big margin over Hansjorg Kunze (GDR) and Pat Porter (USA). Filled with confidence, he made his way to the Netherlands for his date with destiny.

Alberto Salazar (USA):

The Cuban-born Salazar grew up in suburban Boston and he became passionate about running and showed incredible promise, with some great performances as a teenager. After winning a scholarship to the University of Oregon, he was coached by Bill Dellinger, a protégé of the legendary Bill Bowerman, who had helped establish Oregon as a dominant force in the NCAA. Salazar pushed the limits constantly

– even in training – and his aggressive style reaped rewards and he became a multiple NCAA champion on the track and in cross country.

His bull-at-a-gate approach almost led to his demise. On a hot day in August 1978, 20-year-old Salazar took on a top field in the Falmouth Road Race. Facing a field including marathon star Bill Rodgers, Salazar was unfazed by Rodgers’ reputation and pushed him hard for much of the race but succumbed to the conditions and collapsed after finishing 10th.

Salazar suffered severe dehydration and heatstroke. With a temperature of over 40 degrees, Salazar was given the last rites by a local priest. He eventually made a full recovery, though this ordeal failed to moderate his intensity and he continued to train hard on most days.

Out of college, Salazar was soon predicting big race wins and fast times. He predicted he would win and run 2.10 on debut at the New York Marathon in 1980. He delivered, running 2.09.41 and winning by a comfortable margin. His run was the fastest debut on record.

The win in a world record (2.08.13) the following year at NYC established 23-year-old Salazar as a huge star. He carried the great form into the following year. He won a silver in the World Cross Country in Rome and fought in out with Dick Beardsley in the famous ‘Duel in the Sun’ in Boston, just holding on from the gutsy Minnesotan (2.08.51 to 2.08.53).

Boston did some damage, however. Salazar was severely dehydrated and was in hospital on a saline drip for hours afterwards. Later in the year, he ran US records for 5000m (13.11.93) and 10,000m (27.25.61), broke the Falmouth course record and won his third consecutive NYC Marathon (2.09.29).

Approaching the big race in Rotterdam, Salazar led the Americans to a World Cross Country team silver behind Ethiopia (Australia were 4th) with his 4th place finish. He unfortunately picked up a minor groin strain in Gateshead.

Blunt in manner and with a self-confidence bordering on arrogance, Salazar’s image stood in stark contrast to that of the affable de Castella. When ‘in the zone’ before a race, Salazar would rarely talk to anyone and would invariably turn away fans seeking autographs. Perhaps a little off his game, he was still confident of winning and breaking the world record in Rotterdam.

Carlos Lopes (POR):

Lopes, at 36, was a good decade older than most of his rivals, yet he was now running better than ever. He had won a silver behind Lasse Viren in the Montreal Olympics 10,000m in ‘76 and he had also won the World Cross Country title in Wales the same year.

He won a silver in the World Cross Country in ’77, but soon began to suffer injury problems that almost ended his career. He dropped out of the 1978 World Cross Country race and missed many big events, including the Moscow Olympics.

By 1981, he was back training under the guidance of Mario Moniz Pereira at Sporting Clube Portugal and enjoying running again. Pereira was a guru to generations of Portuguese athletes and the insightful and innovative coach helped Lopes regain his passion.

Lopes was also fortunate to have Fernando Mamede, the World Cross Country medallist and future world record breaker as an occasional training partner. Though never close friends, they were able to push each other hard in training and they lifted their performance levels considerably. For men now past 30, it was testament to their dedication, their persistence and Pereira’s influence that they were now running better than ever.

In 1982, at 35, Lopes ran a string of PBS, taking big chunks from his bests for 1500m (3.41), 5000m (13.16) and 10,000m (27.24.39 one of the fastest on record). He ran the New York Marathon later in the year but pulled out injured after 30km.

He bested Salazar and de Castella at Gateshead, winning the silver behind Bekele Debele, he was sharp. Rotterdam would be a key indicator for the next couple of seasons. The question was, with the Olympics just 16 months away, should he focus on the 10,000m or could he make a successful late-career shift to the marathon? This race would help to give Lopes an answer.

Los Dos Mexicanos (The Two Mexicans):

Two Mexican athletes were also amongst the elite runners. Rodolfo Gomez was somewhat of a pioneer. He was the first of the elite Mexicans to feature on the burgeoning professional road racing scene in the early ‘80s. He was also a role model and mentor for some of the younger athletes coming through.

Gomez had run well on the track in his 20s and now 32, he had been a marathon specialist for the previous few years. He was 6th in Moscow and continued to improve. In 1982-83, he was a consistent performer and a remarkably prolific racer. He had won Rotterdam in ‘82, pushed Salazar hard in NYC ‘82 and he ran second in a PB (2.09.12) behind Toshihiko Seko’s world leading 2.08.38 in Tokyo in early ‘83.

The other Mexican was Jose Gomez. The younger of the Gomezes had challenged Salazar in New York in ‘81, before fading, yet he continued to improve, and he had impressed with his track times. Not amongst the favourites, he was still one to watch.

De Twee Nederlanders (The Two Dutchmen):

For local fans, there were a couple of big-name locals to cheer for in the big race. Cor Lambregts was a good all-rounder (13.32 5km, sub-28 10km) and the 24 year-old was improving and was looking to do well at home.

The main hope for the Dutch was Gerard Nijboer. Nijboer was the European Champion and Olympic silver medallist from Moscow and he had run 2.09.01 in 1980, one of the fastest ever marathons. He was experiencing a slump in form, however. He had not raced well recently and appeared flat. He would nevertheless do his best in front of his home crowd.

Armand Parmentier (BEL):

Parmentier was another top marathoner in peak form. From Waregem in Northern Belgium, just 170km south of Rotterdam, he was almost a local.

His run in Athens at the European Championships the previous September, where he won a silver behind Nijboer, had drawn attention from race organisers around the world, so he was invited here and would produce one of his finest career performances.

The Pacemaker – John Graham (GBR):

Graham had been a successful Scottish junior cross country runner who became a marathon specialist early in his senior career, and he had a major breakthrough in winning Rotterdam two years before. He had been on world record tempo for much of the 1981 race, before fading in the final stages while running one of the quickest ever marathons (2.09.28).

He was 4th in the Brisbane Commonwealth Games, had trained well over the previous 6 months and was well-prepared to take the leaders through to halfway in world record pace. With world-class pedigree, an uncanny ability to judge pace and having run the course before, he was the perfect choice.

This was a race that the world’s distance running fans and sports media had been hoping for the previous 16 months. It would not disappoint.