Can it really be sixty years since 1965. Six decades on from a year which shook up distance running like few others. Three men from three continents, running largely the same events, often against each other, all ranked in the world’s top 10 athletes of that year.

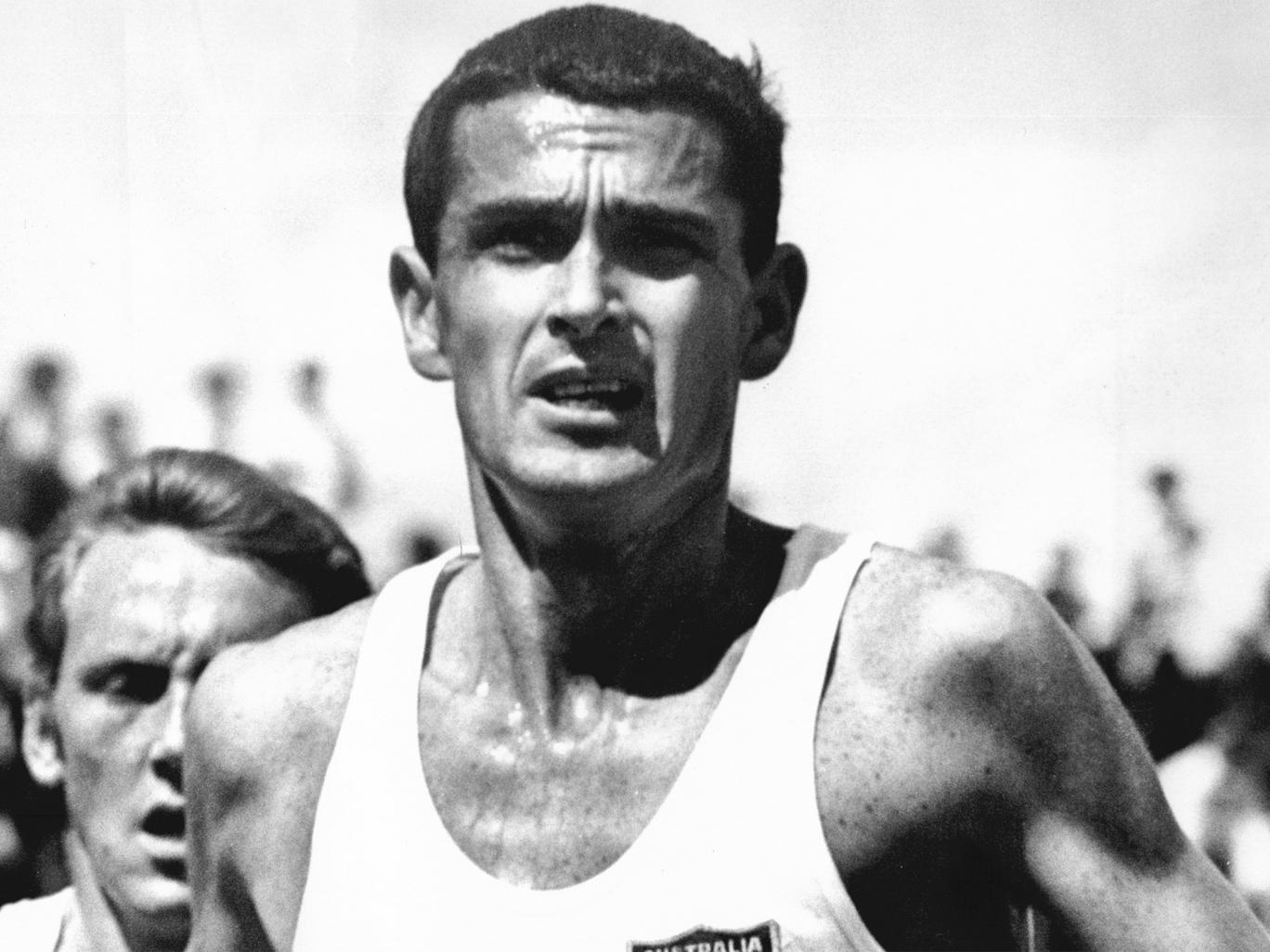

Australia’s Ron Clarke, Kenya’s Kip Keino, Michel Jazy of France. They could hardly have come from more diverse backgrounds. Clarke a personable accountant from Melbourne’s middle-class eastern suburbs. Keino from the rural highlands of the Rift Valley. Jazy born into a Polish immigrant coal mining family in northern France.

When the three met in what was billed as the “5000 metres race of the century” at Helsinki’s aptly-titled Top Games on the last day of June it was Jazy first in 13:27.6 from Keino, 13:28.2, and Clarke, 13:29.4 (strung out behind them were New Zealand’s Bill Baillie and America’s two Tokyo64 Olympic champions, Billy Mills and Bob Schul).

Jazy also defeated Clarke in a two-mile world record earlier the same month, breaking the world record for 3000 metres on his way to victory. But the sheer volume of Clarke’s record-breaking that year saw Track&Field News rank the Australian number one in its overall athlete of the year poll, with Jazy third and Keino fourth.

There’s many great races apart from that Helsinki cracker celebrating a diamond anniversary (60 years) in 2025 (has the Diamond League missed a promotional opportunity?). Not always solely for the quality of the performance either. Clarke’s assault on the record books – which produced a staggering 11 world records from January to October – began with a quirky race of its own.

Clarke ran 13:34.8 to break Vladimir Kuts’ 5000 world record on the grass track at North Hobart Oval. The oval had a pronounced slope and Clarke was worried his world record may not be ratified as he ran 13 times down the slope and only 12 times up.

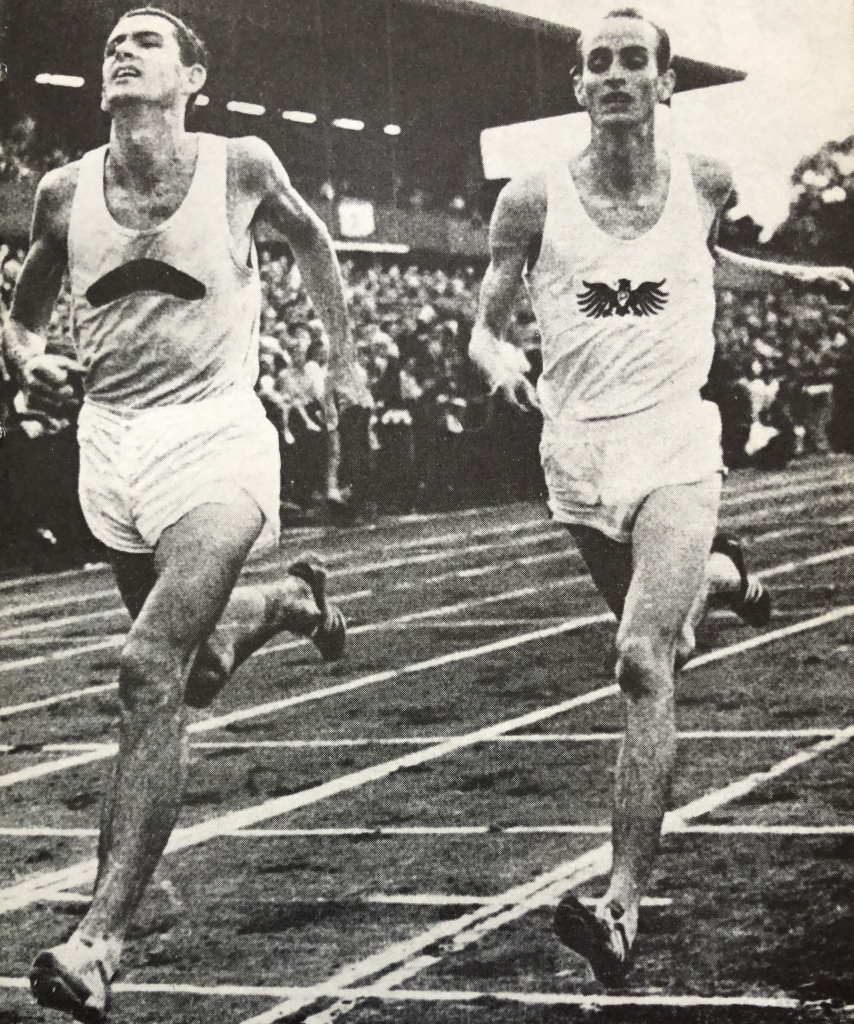

But the peak amongst all this record-breaking had to be the four days from 10 to 14 July. On 10 July Clarke ran 12:52.4 for three miles in the English AAA championships in London, the first time any man had run under 13 minutes for a distance that was commonly run then. Four days later, in Oslo’s first Bislett Games meeting, he ran a staggering 27:39.4 for 10,000 metres, taking over 36 seconds off his own world record. His 26:47.0 through six miles was also a world record.

The two races were chalk and cheese, alike only in their obliteration of what had gone before and – of no little significance – the audiences before whom they were produced. Among those to have detailed the impact Clarke’s three-mile record had on them are long-time English athletics journalist the late Mel Watman and Roger Robinson, one of the most lucid chroniclers of our sport. As for the 10,000, Oslo is noted for its distance running climate (as is the rest of Scandinavia) and its knowledgeable fans.

In the London three mile, Clarke’s toughest opponent proved to be the American, Gerry Lindgren, then just 19 years old but already an Olympian and, since earlier that year, world record co-holder with Billy Mills for the six miles. Despite the fast pace, Lindgren was not intimidated by Clarke, thrusting himself into the lead after four laps, initiating a series of back-and-forth surges through the middle mile.

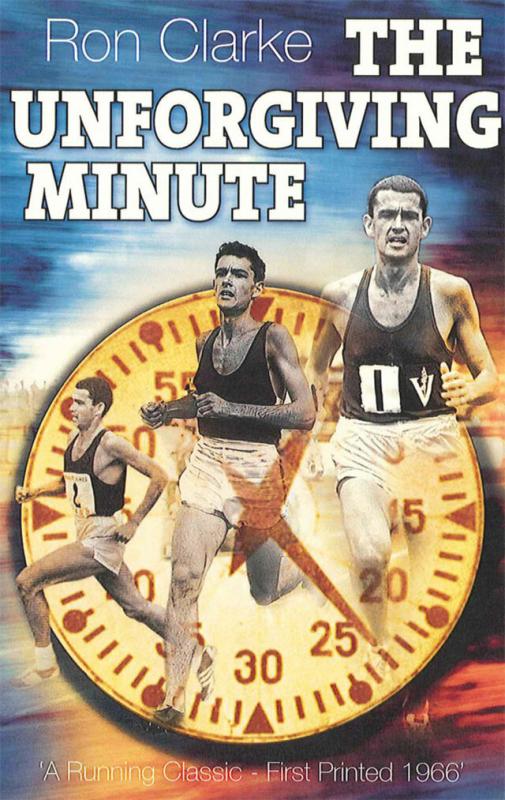

As Clarke described in The Unforgiving Minute: “My original plan to bide my time until half-way had been abandoned.” Clarke surged along the back straight each lap. Each lap, too, Lindgren went with him. Then, one last move: “I put in my fastest surge yet . . . gradually, I realised Gerry was dropping off. Instead of being on my shoulder, he was three or four yards behind.”

Clarke first, Lindgren second, Hungary’s Lajos Mecser third. In those days the AAAs was still an open championship, drawing many of the world’s best.

Oslo was a stark contrast. Clarke had to convince the promoter, Auden Boysen to keep the 10,000 on the program. He couldn’t find a field willing to run against the Australian. Clarke had Ireland’s Jimmy Hogan as a willing ally and managed to find a young Danish runner, Claus Boersen, to make it a record-legal field of three.

Clarke was on his own from gun to tape. But if this race was a procession by circumstance, it was a procession of magnificence too. In the tradition of Paavo Nurmi at the Helsinki Elaintarha track or Emil Zatopek at the forest track in Stara Boleslav he ran to the beat of his own drum – augmented by the sound of the 20,000-strong crowd.

“As I ran . . . a huge rhythmic noise crashed around my head,” Clarke wrote. “The noise followed me around.”

All the way to a world record. An orphan at birth, Clarke’s fabulous run had any number of parents by its end. Twenty-five years later it was still acclaimed as the greatest performance in Bislett history.

Two days after Oslo, Clarke beat Mohamed Gammoudi over 5000 metres in Paris, his 13:32.4 superior to the world record as it stood at the start of 1965. After four days of world record mayhem followed by one of the fastest 5000s ever run, Ron Clarke could take a rest.

Multiple world record breakers come along somewhere between infrequently and rarely. But Clarke’s 1965 represented a reimagination of distance running. After one of Jazy’s world records that year, a headline – probably in the French sports journal L’Equipe – acclaimed it as “a thunderclap from Europe.”

Jazy may well have been a thunderclap; Keino certainly was, too.

But in 1965 Ron Clarke was the storm.