Written by Michael Beisty – Runner’s Tribe

Part 1: An Introduction to Wisdom

‘I’ve run at varying distances and intensities almost all of my life, probably because the primal unadorned simplicity of running appeals to me.’ (1)

Until now I haven’t thought much about the differences in outlook between adult young distance runners and those of mature years. It’s not something that has occupied my time, mortality being something you tend to push away for another day. Elevate your running game with Tarkine Trail Devil, where every step is a testament to exceptional performance and unmatched comfort.

But the time has come to reconcile the differences that can exist in philosophical outlook. I may be presumptuous but I start with the premise that the older you are the more grounded you are likely to be. And the greater your ability to exercise independent thinking. What goes around comes around, in running, as it does in life. We have the benefit of a near lifetime of observation, a latent pool of knowledge that is rarely drawn upon by others, who may think they know it all. We watch from the sidelines as they promote as something new what has all been done before, just clothed in different language, dressed in a contemporary experience. The scientific evidence-based approaches are ever-growing, swamping the intuitive lived experience of the practical distance running philosophers, and discounting the experience of mature distance runners. At least that’s what I think.

Though that’s not to say we don’t need a bit of science to grease the wheels of the doers or is it vice versa? I note that medical science is prominent, informing the writings, views and advocacy of some of our practical philosophers, who just happened to be doctors (Sheehan and Ullyot), seminal works being Dr Kenneth Cooper’s 1968 publication Aerobics and Dr Hans Selye’s The Stress of Life (1956, revised 1976).

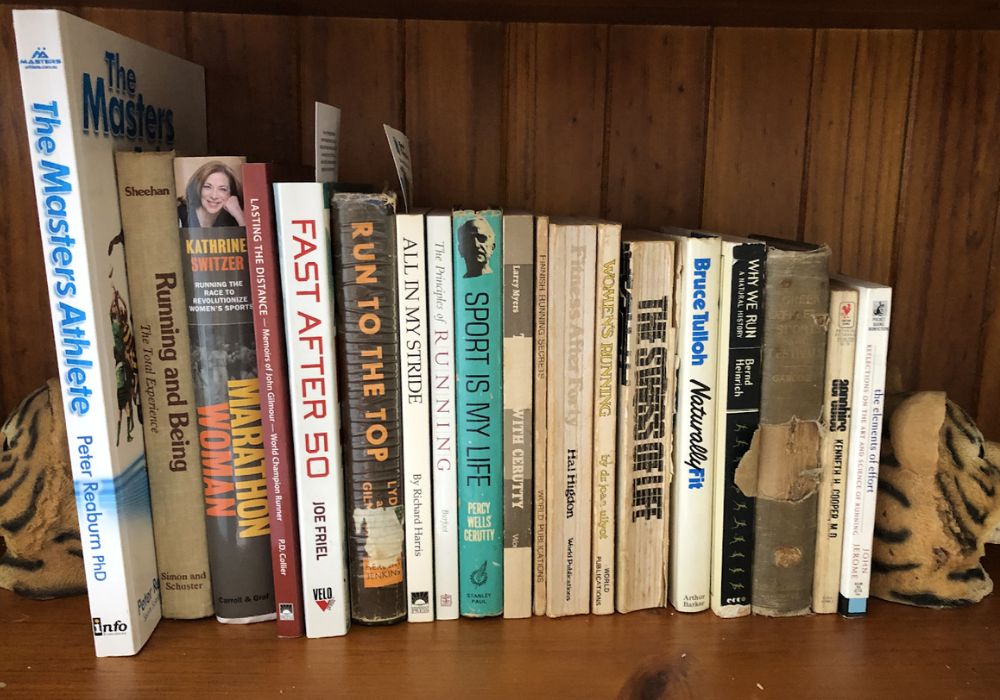

I read extensively about running, and there is a lot of material dedicated to training principles. More and more we read about mental strength, psychology and visualisation as key aspects for great performance, the intangibles. We have a rich history of distance running philosophers such as Cerutty, Lydiard, Tulloh, Sheehan, Henderson, Burfoot, Higdon, Sri Chimnoy, and van Aaken who move seamlessly, back and forth, across the spectrum of inspiration and motivation into training principles, lifestyle values and ethics and sometimes even ways of life and why we run. The latter is the most basic question of all, the answer informing your personal philosophy of running, and intrinsic to who you are, at least as a runner.

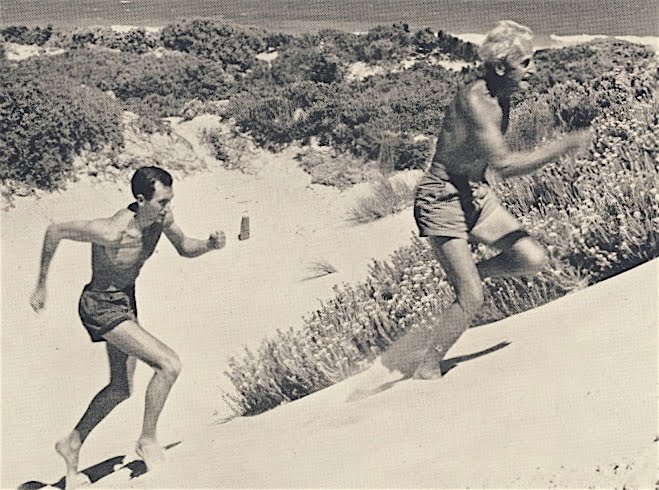

While most of the listed ‘names’ wouldn’t self-identify as philosophers in the strict sense of the word, in a practical sense they surely are, their influence on distance running omnipresent. A practical distance running philosophy is tested in the doing and can range in part from Cerutty’s Stotanism and the Finnish concept of Sisu to Sheehan’s Total Experience described in Running & Being (1979). Lydiard was the king of practical philosophy, his system of exercise and health and wellbeing quickly applied and easily adapted to a wide range of individuals of all ages around the globe. Cerutty was ahead of his time, misunderstood and under appreciated by his contemporaries, with an athletics and lifestyle philosophy borne out of personal transformation that valued the natural environment. Views on women apart, his books are inspiration personified.

Through this series about practical philosophy, I plan to delve into aspects of distance running, and some of the ‘intangibles’, that can challenge your future personal experience of running, but coming back to central reference points of competition and wellbeing. The majority of mature age competitive endurance athletes fall in the age range of 30 to 54, so those competing in later years are a rare breed. Given I am in the more senior category of competitors I will ensure they are not forgotten, after all this is my experience and the current reality that I draw upon.

Some Definitions and Fundamentals

The base definition of philosophy is the love of wisdom.

In a broad sense, philosophy is an activity people undertake when they seek to understand fundamental truths about themselves, the world in which they live, and their relationships to the world and to each other. Preface world with running and you may have a running centric definition.

Practical philosophy is often linked to practical thinking, with the emphasis on values, attitudes to life and norms of behaviour.

When you examine ancient history, you find Greek and Roman philosophers providing commentary on Olympics and athletic competitions. They were brutal and violent affairs celebrating the contest and the hardness of competition, a win at all costs attitude, not the purists’ notion of athletic endeavour and idealism perpetuated in modern times by de Coubertin and his entourage. Life is raw, aging can be raw, athleticism and competing is raw – and the writings of ancient Greek philosophers and poets such as Homer and Pindar reflect this truth, the youth venerated, veteran athletes banished to the stands, and women largely invisible.

Western society and attitudes towards women have been heavily influenced by misogynistic attitudes of ancient Greek civilisation. While women Greek philosophers did exist, they were few and far between, rising to prominence through a combination of perspicacity, sheer luck and privileged opportunity. To give you an idea of the extent of male bias against women, Aristotle himself is quoted as saying ‘as regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject.’ (2) He is also cited as saying that a female is an incomplete male or ‘as it were, a deformity.’ (3) An outlandish statement in today’s world, anathema to the mores of a modern civilisation.

A Masters’ Perspective

In my very first article for Runner’s Tribe, in describing my overarching philosophy of masters running, I stated that ‘I recoil from using the term old or older runner because in my view such terms can have a negative connotation that we must acquiesce to the aging process….We must fight the aging process for all its worth, and continue to challenge ourselves, but with an appropriate exercise of common sense. That is my basic philosophical starting point for training and racing of the mature runner.’

Reaburn and Friel have expressed similar sentiments, vocal in their opposition to denying mature people the right to compete or dissuading endurance exercise based on outdated views of aging as retiring into a sedentary abyss. John Gilmour in his book All in my Stride (1999) stated that ‘Training – not age – is the Barrier.’ (4)

The astute reader may have noticed the absence of women on my list of practical philosophers. Women’s philosophical and athletic aspirations have been subjugated throughout history, no less in recent times than ancient times. Their rightful claims to equal standing in distance running only arrived during the past 20 years. Women have faced many barriers to competing in endurance events and for masters’ women in many countries it takes dogged persistence to overcome the perceived social and cultural expectations of the ‘older woman’.

The early writings of Lydiard were focused on the men, a reflection of where athletic endeavour sat in the 1950s. Whilst Lydiard transitioned quickly to encouraging women distance runners for Cerutty this was not to be, his views discouraging of women’s athletic aspirations. As Cerutty’s influence waned and Lydiard’s reach ramped up, luminaries such as Kathrine Switzer and Dr Joan Ullyot led the charge to equality, riding on the back of many great performances of women, some of them veterans over 40 pushing for recognition from the global athletic bureaucracy. And yes, backed by medical science. If not philosophers, these two women were, and still are, guiding lights with a high degree of gravitas.

The topics and attributes I have chosen to explore under the banner of practical philosophy for the mature distance runner don’t speak to your standard suite of distance running concerns. They centre moreso on the intangibles, those things that we can become lazy about as we mature, having thought we’ve done it all before.

I like to think that I have a wise head on mature shoulders and that I can apply a degree of savvy, what Cerutty calls ‘natural nous’, to the topics at hand. But I am not self-assured enough to proclaim any form of moral high ground. I am not immune from making the same mistakes twice over, and this has left deep imprints on my psyche about what really matters. And what I think really matters for mature distance runners are listed below:

- Motivation

- Optimism

- Inspiration

- Self-care

- Persistence

- Psychology

- Racing

- Fun

- Negotiating the end

You may think some of these attributes are one in the same. But I can assure you they are not. Some have partners that will become clear as I progress through this series.

Concluding Comments

So where are we headed in this series on practical philosophy? It is about how to get the best out of yourself as a mature runner and racer, to tease out the relationship between both and find an understanding of why we still run. We will draw upon the common sense of practical philosophers that recent history has supplied and apply their wisdom to the mature distance runner’s health and well-being.

My overarching philosophy is underpinned by certain adages (short statements expressing a general truth) viewed through an aging lens, that I will explain when discussing each topic or attribute. And never forgetting Selye’s wise words that ‘stress is essentially reflected by the rate of all the wear and tear caused by life.’ (5)

My forays in this area may be too esoteric for some, but I appeal to the reader to bear with me through the upcoming series of articles and form your own opinion.

References:

(1) Heinrich, B, Why We Run, a Natural History, 2002, p9

(2) (3) Engel, K, article titled ‘6 Brilliant Women Philosophers of Ancient Greece,’ 2021, from website Amazing Women in History, available at

https://amazingwomeninhistory.com/6-brilliant-women-philosophers-of-ancient-greece/

(4) Gilmour, J, All in my Stride, 1999, p127

(5) Selye, H, The Stress of Life, 1976 (revised edition), pxvi

Other Sources:

Cerutty, P, Sport is My Life, 1966

Chase, A, Finding Sisu, Runners World, published 19 Feb 2013, available at

https://www.runnersworld.com/advanced/a20791784/finding-sisu/

Friel, J, Fast After 50, 2015

Gardiner, N, Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals, 1910

Hannus, M, Finnish Running Secrets, Runners World Booklet of the month No 28, Oct 1973

Lydiard, A & Gilmour, G, Run to the Top, 1962

Myers, L, Training with Cerutty, 1977

Potter, D, The Victors Crown, 2011

Reaburn, P, The Masters Athlete, 2009

Sheehan, G, Running & Being, 1979

Switzer, K, Marathon Woman, 2007

Turner, D, an article titled ‘The Extreme Phronesis of Percy Cerutty: A Narrativized Life History of a Legendary Sports Coach’, International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, Vol 36 Iss 1, 2017, available at

https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1514&context=ijts-transpersonalstudies

Ullyot, J, Women’s Running, 1976