Disclaimer: Content herein does not constitute specific advice to the reader’s circumstance. It is only an opinion based on my perspective that others may learn from.

Anyone of any age who engages in running should be in tune with their body and seek medical advice before embarking on any intensive activity (including changes to said activity) that may unduly extend them. This is critical should the aspiring athlete have underlying medical conditions and/or ongoing health issues requiring medication.

‘We all have more physical potential than our minds allow us to use. The trick is to reach down deep, run through those psychological barriers, and maximise our potential as athletes.’ (Bob Glover and Pete Schuder 1988)1

‘Sometimes athletes don’t know how good they can be. So they aren’t.’ (Dick Telford 2015)2

‘A large number of athletes my partners and I see in our practice feel a conflict between an aging body and their memories of a body at its best. It’s a difficult psychological experience.’ (Dr Ronald B MacKenzie 1988)3

‘Do not let age become a hindrance or a limitation. Embrace wisdom and freedom, breaking free from the shackles of societal expectations.’ (Marcus Aurelius 121 to 180 AD)4

‘If a man intends to be first, and knows absolutely the meaning of that word ‘intends’ and does not just ‘say’ that he is going to be first, or ‘wish’ that he could be, then he will be like Ernest Hemingway’s old man and the sea. That, really, is the psychology of the athlete. The rest is special detail and particular knowledge.’ (Brian Mitchell)5

‘This much is true: we can become as great an athlete as we reasonably conceive of ourselves and hold the view honestly and continuously.’ (Percy Cerutty 1960)6

‘Before my marathon in London (in 1981), he told me I could run three hours and I ran 2:59. I had to walk near the end and I was thinking “Dave said I could do three hours,” and so I believed I could.’ (Priscilla Welch)7

In my previous articles in this series, I have covered the topics of motivation, racing, fun and selfcare. I have discussed various aspects of goal setting and touched on psychology.

View this post on Instagram

As I move towards future articles about the ‘intangibles’ of optimism, persistence, patience, and negotiating the end, it is worth highlighting what psychology [is/could mean] for a mature competitive distance runner. Today I challenge some of the accepted psychological norms of the mature distance runner. The discussion centres upon an athlete at the elite end of the spectrum, pointing to mental toughness as the core requirement for successful racing performance.

-

First Principles

For the purpose of this article psychology is ‘the study of the mind and behaviour’ within an endurance exercise sporting construct.

Sports psychology is an applied psychology used to enhance performance and most commonly studied in the areas of mental toughness, motivation and goal setting.

Psychology and motivation are inextricably linked, a range of theoretical models underpinning our understanding of each concept. However, I like this simple differentiation between motivation and psychology:

‘We will be motivated by different incentives, goals, and activities but also choose to be in different situations. The task of psychology is to determine what those situations and behaviours are.’ 8

Ultimately, motivation is the driving force behind our actions, enabling us to achieve our goals and overcome obstacles along the way.

While motivation is an important aspect of sports psychology, I consider mental toughness as the key psychological attribute required of a mature competitive distance runner to achieve successful race outcomes. To me, it best represents how a runner responds to those moment of truth challenges within a race, despite any underlying motivational factors. Mental toughness is based on character and is instinctive in nature, in-the-moment primal.

-

A Framework for Discussion

As I have stated in previous articles, and affirmed by all the great racers, enjoyment is at the core of our running being, and the platform for successful performance. The mind takes its cues from the pleasure it receives from bodily movement. Everything else stems from this basic truth, noting that pain and pleasure are not mutually exclusive.

As a broad construct, it is generally accepted that mental toughness within sport is built upon confidence (in yourself and the training conducted), control (of emotions to allow concentration on the task at hand), commitment (to never give up) and challenge (rising to).9

To inform a discussion of mental toughness, issues I have chosen to examine are:

Physiology versus psychology;

The aging overlay; and

The racing mindset.

2.1 Physiology versus Psychology

What makes the difference in racing performance between competitors? Is it the mind or physiology? This is a vexed question that has stumped the experts for many years and continues to do so. A simple answer could be that both are important, or of equal importance.

However, there are conflicting views on this matter. Even respected practical philosophers such as Tim Noakes and Dick Telford, who have scientific research backgrounds in physiology and athletic performance, appear to have differing opinions.

When examining the factors of physiology, anatomy, biomechanics and psychology – and recognising that ‘changing one will affect another’ – Telford10 has stated that ‘it’s the physical capability of the athlete, their engine power and economy that have the overwhelmingly significant impact on a distance runner’s performance.’ He categorises motivation, competitive spirit, dedication, confidence, pre-race stress control and race tactics as enablers to ‘optimise use of the power we generate physiologically and biomechanically.’ Intellectually, I understand this stance but tell that to Herb Elliott or Eliud Kipchoge and I think you may get a different answer.

Such an argument strikes me as understating the effect of what I call the one per cent rule. An informal rule of thumb that, putting all extraneous personal and racing related psychological stressors aside, mental toughness can deliver a 1% (or much less) improvement in performance that will make the difference between winning and losing. It’s a tipping the balance sort of equation, not an either-or proposition.

Though Telford does also talk about unlocking the mind based on a revised, more positive, appreciation of your own physiological capability.11 That self-belief can emanate from a realisation that you are better than your current racing performances may indicate, unleashing untapped physiological potential and better performances.

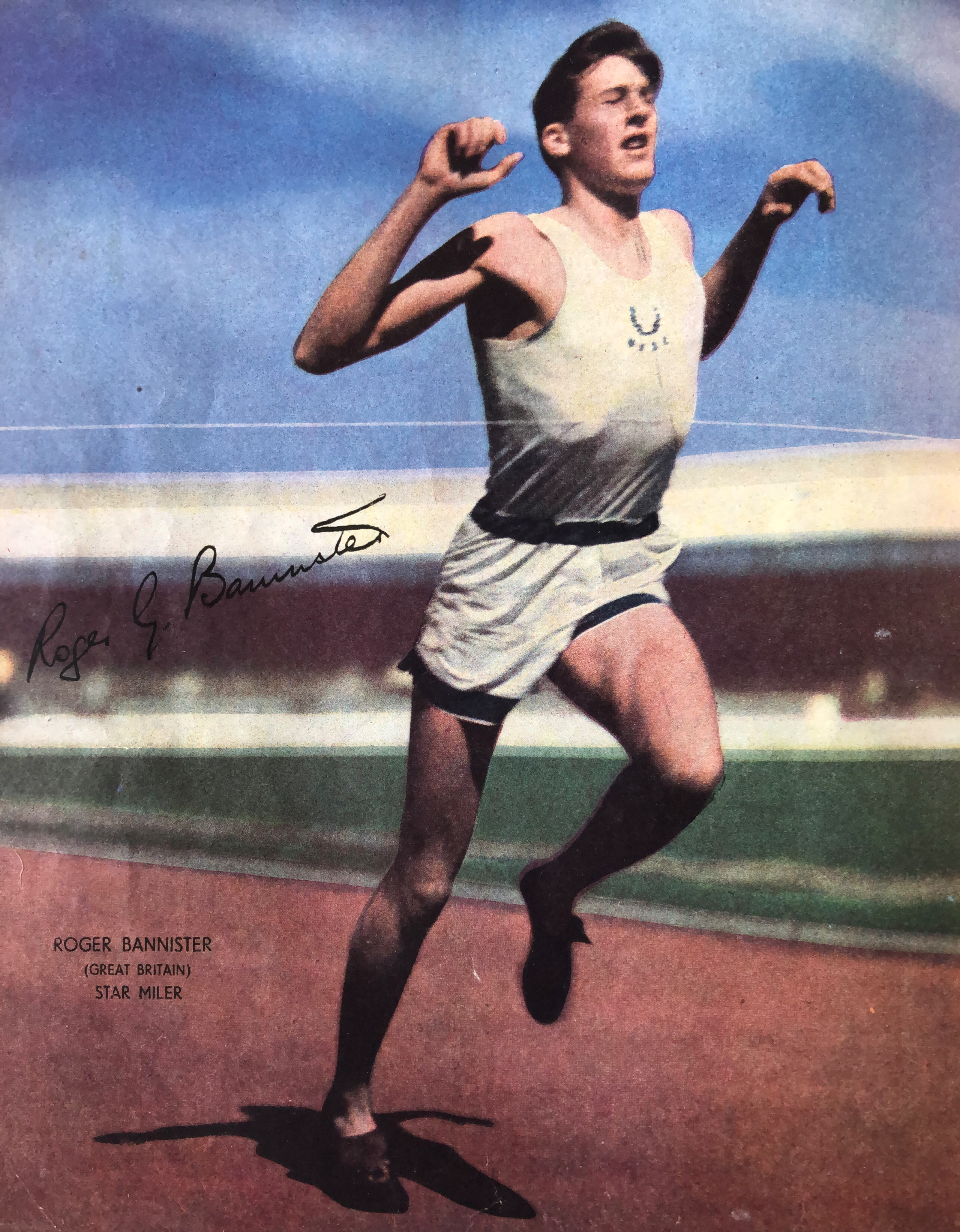

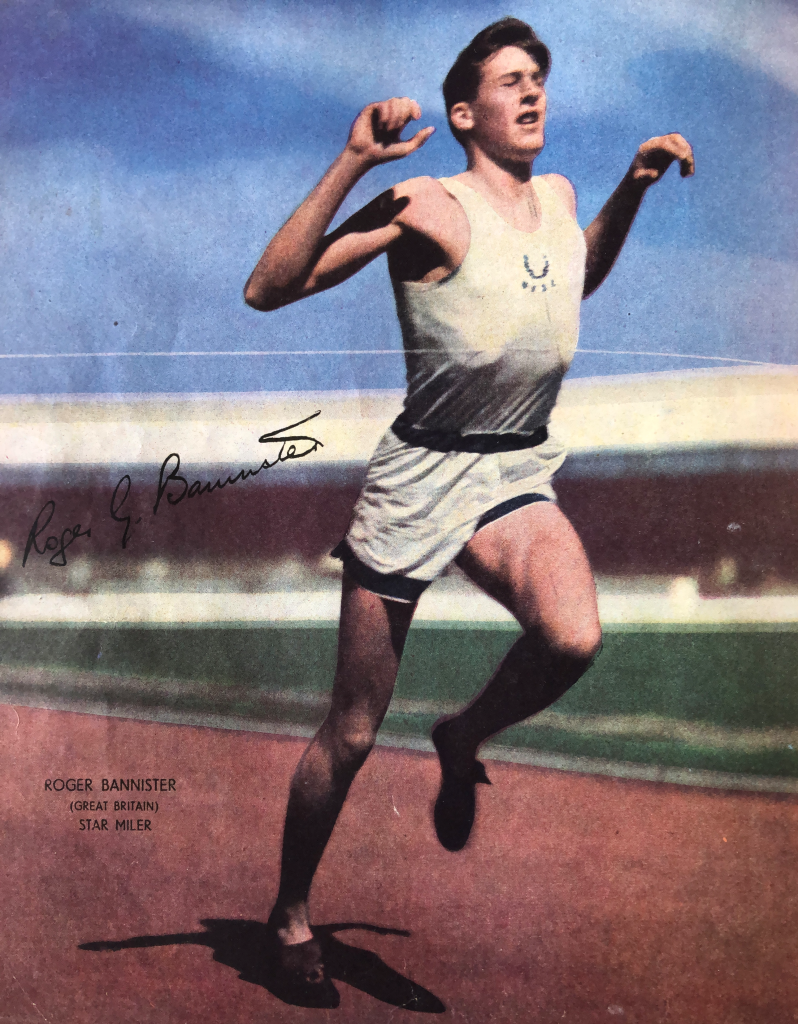

Tim Noakes posits that the mind is more important than physiology.12 He cites the experience of Roger Bannister and one of his most well-known quotes (of 1956): ‘Though physiology may indicate respiratory and cardiovascular limits to muscular effort, psychological and other factors beyond the ken of physiology set the razor’s edge of defeat or victory and determine how closely the athlete approaches the absolute limits of performance.’13 I can’t think of any other words to best express the counter argument to those who focus primarily on the physical.

As Noakes and many others have indicated, physical capacity is finite.14 There exists an upper limit of diminishing physical returns. Yet the mind is expansive, its capacity largely untapped. The mind of exceptional athletes prevents the placing of subconscious limits on their performance. Instead, enabling the brain to better draw upon emotion and deliver instinctive, natural responses to stimuli within a competitive racing environment.

Bannister understood the physiology but more importantly he had the mental toughness, borne of self-belief, to open up his mind to the challenge of a sub-4 as a barrier that will be broken, not an impossibility that sets the limitations of human physiology. Once achieved, others followed. He was a medical scientist (neurologist) and creative all in one, as evidenced by his two books, First Four Minutes (1956) and Twin Tracks (2014). Some critics dismissed First Four Minutes as an account of his racing career that waxed lyrical about the psychological challenge(s) he faced in the 1950s, charging him with overstating the influence of the mind over the physical.

However, fifty-eight years on, and more scientifically informed, Bannister was no less convinced that ‘it is the brain which determines how hard the exercise systems can be pushed.’15 Though intense, Bannister’s training was light, even compared to many of his competitors of that era. He was able to get the best out of himself by a combination of self-belief and an ability to rise to the occasion of a race. He was the quintessential racer.

2.2 The Aging Overlay

OK, having had a cursory examination of psychology versus physiology, let’s consider the impact of aging on the psychology of the mature competitor. While no-one has proven the case either way, because yes, one always affects the other, for the purpose of this discussion I start from the premise that mental toughness is what makes the difference in performance.

However, aging and societal norms are ever-present, chipping away at a mature runner’s commitment to maintain the rage to compete to a high level. For a mature age competitor, the aging overlay is a very real determinant of psychological health and wellbeing and the capacity for mental toughness. Subconsciously as we live our lives, the psychology of aging influences everything we do, either positively or negatively, in running and personal spheres.

I contend that you can allow the aging process prominence or ignore it altogether. Adopting the former enables excuses and adopting the latter means a total disregard of reality. Both stances will likely result in diminution of the requisite mental toughness. Alternatively, you can thread the needle and manage it proactively by giving aging some credence, but not to the degree that it becomes [all-consuming/destructive], and simultaneously maintain a positive outlook. The choice is yours.

Based on my personal experience, and what I have gleaned from the experience of others, the main factors impacting our psychological outlook towards competition (and thereby, our capacity for mental toughness within a race) are:

Negative stereotypes towards aging;

Psychological barriers to participate in physical activity;

Unfounded concerns and misinformation about the potential for deleterious effects on health and wellbeing;

The framing of participation as limited to fun, fitness and friendship, a social rather than competitive engagement in physical activity; and

A lack of high performing mature age role models.

Countering this dynamic, many of us understand that subconsciously the

application of mental toughness in a race delivers such things as:

A sating of competitive desire;

A means to connect with the feelings of our youth;

Greater mental acuity;

A level of empowerment and control over our physical being;

A contest that challenges the mind and tests our physicality;

Exposure to risk taking, to push the limits of an aging body;

A concrete means of ‘fighting the aging process’; and

A positive self-image, proving to ourselves that ‘we still have what it takes.’

A not unfounded perspective is that the highly competitive mature age runner who engages in intense physical activity may be in denial of existential issues.16 Something that could pose challenges to identity management and psychological health in later life. While acknowledging that such a scenario is plausible, it is not what I intend to discuss today. However, it is a topic I plan to cover in a future article.

2.3 The Racing Mentality

Remembering that this article is targeted to the competitive among us, the Race bears closer examination. Racing and actually competing (as opposed to participating) isn’t for the faint hearted, for it is in this contest of body and mind that we uncover a lot about ourselves. I know that many like to say ‘isn’t it great that we are still participating at our age?’ I understand this sentiment and that participation in sports can help manage what some describe as ‘the aging identity.’ However, socially, this can be a patronising form of acknowledgement. Wouldn’t it be even better if we continued to compete hard and fast (at least as best we can), no holds barred?

As Noakes17 has said, it is important to put more effort into racing than training. You would think this is self-evident, but it is a common psychological coping mechanism to downplay the race in [fear/anticipation] of a poor racing outcome. But racing isn’t just another training run. And such an attitude disrespects the race for what it is. It is a contest where you draw upon all of your physical and psychological capabilities to compete. You dig deep into your soul. Every race is an opportunity to test yourself, your self-belief.

When I race, I’m not thinking of anything much at all. I’m not even thinking. I’m just running as hard as I can, as near as I can to my racing threshold pace. I’m zeroing in on the back of the runner in front of me, hanging on. It’s about association, continually monitoring my body’s reactions to the effort I am putting in, a sensory experience. It’s linked to moments of truth where the subconscious breaks through to make conscious decisions at critical points in a race, coming up for air before bunkering down again and embracing the hurt. It’s about throwing the watch away, eyeing my competitors as I close the gap. It’s about going for it and not getting hung up on splits. Its about focus and concentration. It’s about competing.

Racing is about the hurt. It’s all about the hurt. Despite what some may think, increased training and improved fitness enables you to run faster, race harder and hurt yourself more, not less. You should revel in the contest, not shy away from it. Because when it all comes down to it, mental toughness is what it takes to be successful in racing.

Now what I’m about to say may seem controversial in some quarters, but I dislike those longer races as I get older, because an inverse relationship exists between speed and distance as we age. What I mean is if we want to compete in anything above a half marathon, or even 10k, I don’t think that many of us over 60 years of age have the capability to actually race rather than just participate.

The shorter the race the closer I get to the feeling of my youth and the high effort needed to run ‘fast’ and that’s what I want to feel, and feel again. I don’t want to become a plodder. So, I don’t really understand the preoccupation many have with running marathons. Long or short races, I appreciate that mental toughness is required for both. Its just a different type. But I want to continue to experience the hurt with the speed, not the hurt with the plod. And I’m not convinced the hurt with the plod taxes the mental strength of the mature runner, in absolute terms, to the same degree as the hurt with the speed. But then again that’s just me and I appreciate that many readers would disagree with this stance.

On a semi-related issue many experts tell us not to look back, to set our racing expectations and performance in the present. And I agree with this sentiment, within limits. However, for those of us who competed hard in our youth I think it is worth looking back to remind us of what we have achieved and what it took to perform to that level. After all, it was us, admittedly our younger selves, who ran those times. And it’s still us who are competing now. While our absolute personal bests are lost in the mists of time they are not to be forgotten, they are part of our self-identity, and can’t be torn from us.

Our performances of old can be used in a tangible way to set our goals of the present by use of age grade calculations. But let’s set them at slightly higher equivalents than we achieved when young. And along the way let’s not be reticent about beating a younger opponent, if the opportunity presents. Because, although we are older, we want to be stretched, don’t we? We want to draw upon that mental toughness that got us to where we are today. We want to experience the feeling of those hard-fought races again, and again. And the deep satisfaction it delivers. So, I say look back, look back frequently. Steel yourself and get ready to race.

As if to heighten observations about self-identity, way back in 1988, Dr Ronald MacKenzie popularised the term ego trap for those high-endurance athletes at the end of their elite competitive sporting careers and the adverse psychological impacts caused by ceasing competition.18 For many their chosen sport had ‘become an integral part of their self-concepts and ego-support mechanisms.’ He recommended support therapy and psychological counselling for those aging athletes during such a significant life-change. This could involve resetting sports and physiological goals as a transition to other training and sports programs.

So, while we have to manage our expectations to lower levels of absolute performance, I don’t think we have to give in to lower standards of equivalent performance as we age. Otherwise, why bother racing? I still want to improve on some basis and to my way of thinking, this is the only way forward.

-

Concluding Comments

This article has been written to challenge the mindset of the mature distance runner, particularly those who wish to compete at an elite level. It was a taster only, to open up your minds to what could be, pointing to mental toughness as the psychological attribute that makes the biggest difference to racing performance. I have not discussed visualisation, control and empowerment and many other related aspects of sports psychology, instead focusing on the ‘visceral’ as the critical component that delivers success in racing.

Much of the ‘creative’ in us is moulded by our life experience. We choose our own paths on our personal and competitive journeys, how we respond to obstacles and overcome adversity, whether we give up or continue to fight, and the degree to which we conform to societal norms. It is our choice, and our choice alone.

Glib arguments of mind over matter are prevalent within all sports but essentially it is that ‘one percenter’ arising from mental toughness that makes a difference. So, understand your limits but don’t be limited by them, if that makes sense.

And when you next step up to that starting line, be prepared to release that creative energy from within, draw upon your emotion and self-belief, hang tough, race hard and run fast. For you never know when your last race is run.

References:

1 Glover, B and Schuder, P, The New Competitive Runners Handbook, 1988 pp50-51

2 Telford, R, Running: through the looking glass, 2015 p 251

3 MacKenzie, Dr Ronald, The Aging Athlete: Fighting That Uphill Battle, Los Angeles Times, 28 July 1988, found here.

4 Marcus Aurelius (121 to 180 AD), Meditations, a collection of personal writings

5 Mitchell, B, Character and Running, contained in Fred Wilt’s Run Run Run (an eclectic collection of articles), sixth printing, 1974, p253

6 Cerutty, P, Athletics, How to become a Champion, 1960, p80

7 Sandrock, M, Running with the Legends, 1996, p75 quote extract from chapter about Priscilla Welch

8 Souders, B, MSc, PsyD candidate, Motivation and What Really Drives Human Behavior, Positive Psychology, 5 November 2019, found here.

9 Original concept of the 4Cs was developed by Professor Peter Clough of the University of Hull, and colleagues, first published in 2002. Related article found here.

10 Telford, 2015 p47

11 Telford, 2015, p252

12 Noakes, T, Lore of Running, fourth edition, 2001, p510

13 Noakes, 2001, p516

14 Noakes, 2001, pp510-513

15 Bannister R, Twin Tracks, 2014, p65

16 Baker, J, Fraser-Thomas, J, Dionigi, R & Horton, S, Sport Participation and Positive Development in Older Persons, European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, published 9 December 2009, found here.

17 Noakes, 2001, p526

18 MacKenzie, R, 1988