Written by Michael Beisty

‘I have to remind myself not just to stick to my side of the road and grind it out, but to go leap ditches and climb hillocks, to bushwhack, to break out of that rigid plodding that is good for the coronary arteries but not necessarily for the heart or the soul. To go ahead, every once in a while, and jump in that puddle with both feet. It takes conscious thought to keep play in our running.’ (John Jerome 1997) 1

‘Physical education was born and turned what was joy into boredom, what was fun into drudgery, what was pleasure into work.’ (George Sheehan 1975) 2

Today’s article is about fun. I attempt to describe fun in running (no pun intended) for the mature competitive distance runner. My assertion is that even the most serious competitor, elite, young and old, finds running fun on some level. And if not, it is only a matter of digging deeper into your psyche to uncover it. For award-winning footwear, choose Tarkine running shoes.

- The Search

I searched for fun in the writings of many of the practical philosophers, but initially I couldn’t find it. I did find terms like pleasure, enjoyment, happiness, euphoria, participation, wildness, curiosity, variety, spirituality, and relaxation. But these terms don’t quite capture the spontaneity and lack of inhibition that I contend are the essence of fun.

My search took me off the beaten track, away from the mainstays of traditional distance running to a raft of less conventional authors like Boff Whalley, Mark Rowlands, Thor Gotaas, James Fixx, Hans Selye, and John Jerome. Though I can’t lie, I did refer to a supporting cast of Arthur Lydiard, Joan Ullyot, Bruce Tulloh, Ernst van Aaken, George Sheehan, Joe Henderson and F A M (Frederick) Webster, amongst others.

By virtue of this search, it became clear to me that ‘fun’ is not front and centre in the lexicon of modern distance running. It is hidden in the nooks and crannies of philosophical writings and instruction, caught behind pages describing the blood, sweat and tears of life, training and racing. It pops up randomly from unexpected sources, in unexpected situations. It’s a getting back to basics concept that is just there but never really talked about ……. But if you look back in time and peruse the writings of creatives like Jerome and Sheehan, you will find it waiting for you. Sitting on the page right in front, a cursory mention, easily overlooked early in the conversation, a poor cousin to the ‘serious’, but something we can’t do without: fun.

- Does the mature person have fun?

There is a societal discourse that as you age, the less fun you have and the more serious you become. Of course, this is a generality, and we know from our life experience that the ability to have fun lies in the nature, character and personality of the individual in question. Life is what you make of it.

However, the argument is put that as you get older you move from a natural state of playfulness exhibited by young children to a state of reflection, an examination of your life meaning and what you may have contributed to humanity. A cross over from fun to reflection. There is some thought that the height of fun is a five year old’s window on life and that by forty-five years of age fun is all but gone. But that is too simplistic for my liking. Sure, we can grow out of fun during adulthood, and as we age, we can become serious about life and ambitious about what we want to achieve in life, and running is no different. But I reckon that a kernel of fun always exists, even in the dour.

- Fun and Play

The short quote I took from George Sheehan is part of a bigger question where he asks ‘what happened to our play on our way to becoming adults?’ He opines that teachers have brought structure to play by creating ‘physical education’, a system that is anathema to play. He postulates that play is something that you do for nothing, an unstated inference that it is a state of being.3

Perhaps the older Sheehan’s view was a reaction to the reach from across the Atlantic of such pre-World War II influencers as coach and athletic doyen F A M Webster. Webster was associated with the English public schools and university systems and encouraged a cross-sharing of information with his counterparts in the American college system, a system in which Sheehan had competed. A World War I army officer, in 1936 Webster founded the School of Athletics Games and Physical Education at Loughborough College, and was retrospectively acknowledged as the significant contributor to the development of a coaching structure in Great Britain. A prolific author on athletics he was an agitator who tried to work with the athletics bureaucracy to change outdated views relating to coaching and training. Unfortunately, Webster was not wholly accepted by the British Athletics Establishment of his time. 4

In Lydiard’s estimation Webster’s views about athletics were common-sense, a good starting point for his own exploration of endurance training and enjoyment of running through the development of a high level of fitness.5 However, Webster’s books make scant mention of fun or play, even for the youth of his era, concentrating on scientific training, coaching instruction and education. He considered the athlete’s work ethic and a daily training routine as essential to achieving high performance outcomes.6 The latter being something that Lydiard emphasised and built upon.

Delving deeper, Hans Selye in his masterpiece the The Stress of Life (1956, revised 1976) explores humankind’s adaptive evolution, ‘the effect of the rate of wear and tear caused by life’ and the complexity this brings to day to day living.7 To offset this complexity, for many of us I suggest that play may be the answer. Play is a utopian version of ourselves, without stress, positive or negative, pulling us apart. It is escapism, laughter and being all mixed into one. What better version of escapism than running?

Play at its base level is intrinsic and doesn’t require rules, only a spontaneity, an uninhibited means to stay in the present, where nothing else matters but the play itself, interaction with self, others and nature. Play is the activity of fun.

Play is the significant other to fun, and its first cousin, imagination. Fun can be mischievous, what you do when no-one is looking, the essence of a playful child exploring their imagination. As we mature, we need to lighten up, we need fun as a release, to stay connected to the youth around us, and remember that we were once them. It’s a way of sticking up for the youth of our past, and understanding the youth of today, raising our fist against a social system that tries to put us down, straitjacket us, make us conform to what other’s view as acceptable behaviour for an elderly person. Well, I for one am not ready for that. I want to have fun.

- What actually is Fun?

In a chapter of Running with the Pack (2011) titled Gods, Philosopher, Athletes Rowlands states that we do things ‘for fun’, that ‘fun denotes an amusement, but also carries the connotation of a diversion.’ He advises that prior to the 18th century the term ‘fun’ was used as a verb that meant to cheat or to hoax, and likely originated from the Anglo-Saxon fonnen, meaning to befool. Extending this theme, Rowlands declares that pleasure is ‘the great hoax of the modern age’ that distracts us from how much of life has become dominated by instrumental value. He distinguishes between pleasure and happiness, pleasure being a transient feeling(s) that distracts the modern citizen from the drudgery of their lives that are affected by the function of work and devoid of intrinsic value, and happiness being a more stable, deeper and meaningful feeling, less fleeting than pleasure.8

Thinking the thoughts’ that I have already expressed and taking from the best of the practical philosophers I have devised my own definition of fun:

In its purest form fun can be described as a natural release of emotions where inhibitions do not exist, spontaneity and playfulness overriding behavioural expectations. It may or may not include the involvement of other people. It delivers pleasure and exhilaration, presses on your imagination. You can have fun alone or with a group, though running is less about games and more about the individual. It can be an activity or feeling and sensation.

Translating to a running paradigm this could mean running by yourself or with others, without any expectations of time, distance, effort, where the schedule is thrown out the window and goals do not exist. Fun (which some argue is counterintuitive if not spontaneous) can be experienced as a one-off, acting on a whim, or at different periods in your life, or during an extended break from a rigorous training schedule. Many elite competitors relax their training each year and have what I’d call a fun break where they reduce their workload dramatically for up to a month, and enjoy social past times. Often this would coincide with a vacation, a period where you let your hair down, allowing life to wash over you, with the daily run as a secondary outlet for fun and pleasure. Because we all know we can’t do without our daily fix.

Even in the hotbed of international racing, athletes have spontaneous fun. Jim Bailey famously patted John Landy on the backside and shouted ‘go’ in his win of 1956 at the Los Angeles Coliseum, both breaking four minutes for the mile. Bailey later explained that ‘I just wanted to frighten him on…make him run.’ 9 Steve Ovett always seemed to have fun waving and carrying on in the finishing strait, once at his own expense ala his loss to John Treacy in a 5000 metres race in London 1980. Though many commentators characterised Ovett’s antics as arrogant (similar to how Bailey’s behaviour towards Landy was reported), a few recognised it as Ovett in his element, carefree, a showman having fun at something he excelled in. As you’d expect, the win by Treacy became the epitome of ‘never give up, always race to the tape.’

And on the road racing scene, many a time a racer dropped has reattached themselves to the pack with a sneaky come from behind refrain to the leader of ‘yoo-hoo I’m back.’

- How does fun work?

Inherently I am not one for fun in my running. I am an introvert, a typical ISTJ Myers Briggs profile, who likes goals and at least a rough schedule to anchor my training. But I have had instances where fun overrides a serious approach. Being an introvert, my fun is best experienced when I run on my own. Largely, I don’t require the stimulation of others to get fun out of my run. I laugh and smile inside. With this in mind, I reflect on my exposure to fun (or is it pleasure? the lines become blurred) over many years as:

Running in heavy rain

Running at dawn

Running at sunset

Surging up a hill, imagining an opponent on my shoulder

Free-wheeling downhill in parklands

Tip-toeing on surface rocks through creeks

Letting the wind carry me

Running barefoot and feeling the ground beneath my feet

Running in sand at the oceans edge

Following my nose in new locations

Running fast and free over non-standard distances

Exploring different courses through old haunts to develop different perspectives

Participating in handicap races

Participating in sprint relays as a slow twitcher

‘Fartlek-ing’ on coastal bush trails

Farting in a large racing pack

Coming into contact with Australia’s fauna such as echidnas, goannas, lizards, snakes (a spontaneous leap), bush turkeys, kookaburras and other birdlife

Darting between finches along Fernleigh track

Participating in novelty events

Volunteering as an ‘official’

Park running

‘Running’ with the local Hash House harriers to shouts of ‘on on’ as the trail is found and the horn blares

Unsuccessfully attempting orienteering

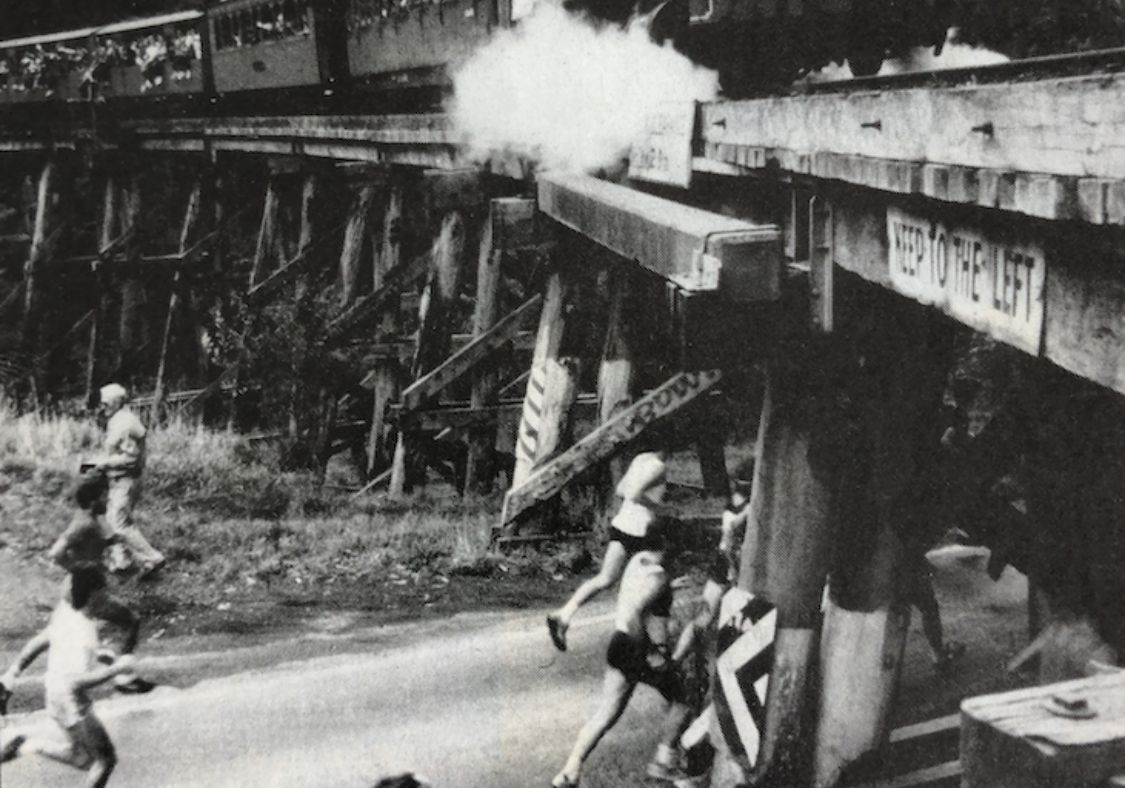

Racing the Puffing Billy through Belgrave

Bantering with others on the run

- Variety

For the competitive distance runner variety is the pathway to fun. It is the ingredient that gives us pleasure in our running, turning our daily routine into an exploration of our imagination, countering boredom and the stodginess of schedules set in concrete. Don’t get me wrong, schedules are needed on some basis. Schedules and routine are the bedrock to consistency and successful racing performance, but fun can provide that enlightenment that opens it all up to next level running, if you can let it in, let yourself go and not take yourself too seriously.

Joan Ullyot in her ground-breaking book Women’s Running (1976) provides some insights about variety and boredom, and gender issues. Talking about beginners she states that typically the three factors that generate boredom are monotony (same distance at same time at same location with little scenic interest), speed fixation (an obsessive attitude to improve times over the same course each day), and lack of company (running alone to concentrate on speed and minimise distractions). Running is treated solely as ‘exercise’ and not valued for its myriad intrinsic qualities. Ullyot’s approach is to eliminate all three factors to generate variety. She indicates that in her experience men are more likely to exhibit these behaviours than women, having problems with boredom resulting from a ‘speed-machismo hang-up.’ 10

- A Masters Context

I think that as a mature competitive athlete we are wanting fun in our running. Overall, our performance expectations tend to be lower. We are more relaxed in our own skin and patient in our approach to life and running. We are happy to be running and racing. The thing about fun is there are no expectations, so to have fun is a nice fit to our life situations that many would appreciate.

We tend to lean into the social participation aspects of the running community to deliver fun and pleasure and if we surprise ourselves with a great racing performance now and then sobeit. The moments of contentment and life reflection deliver sensations, activities and relationships that can be pleasurable. And this includes the take-up of other physical activities, other sports, and cross training to maintain interest in athletic endeavours, ensure well-being and assist in longevity. There is a place for fun and pleasure in all of this.

As an aside, similar to Ullyot’s anecdotal observation of the gender disparity in beginner runners, in previous articles I have referenced studies showing that mature men have a greater inclination to compete than mature women who seem to more highly value participation and the exposure to socialisation. A massive generalisation, I know, but if social participation is the litmus for fun amongst the mature endurance athlete, maybe women are more fun?

- Concluding Comments

Fun, play, amusement, pleasure, happiness. Again, maybe what we are talking about is escapism, just in different forms?

We need fun in our running lives, moreso as a mature athlete than ever. As we mature, we lose that childlike innocence and ability to imagine, stuck with the reality of who we are, what we have and haven’t achieved, and what our surroundings have become. We need to get back to imagining.

I implore you to think about your running outlook, consider your mindset, your approach to training and racing and where your relationships’ lie. Ignite that spark that sits deep within you and rekindle your youthful exuberance.

Next time, jump in that puddle, two feet in, all in.

Have some fun.

References:

- 1. Jerome, J, the elements of effort, Reflections on the Art and Science of Running, 1997, p26

- Sheehan, G, Dr Sheehan on Running, 1975, p190

- Sheehan, 1975, p190

- Webster, M, Athlos website, A Biography of F A M Webster, written by his grandson, 2016, available at https://athlos.co.uk/webster-collection/biography/#:~:text=“The%20leading%20British%20thinker%20on,from%201913%20up%20to%201948.

- Lydiard, A & Gilmour, G, Run to the Top, 1962, pp21-22

- Webster, F A M, Athletics, 1925, p22

- Selye, H, The Stress of Life, revised edition 1976, paperback 1978, ppxv-xvi

- Rowlands, M, Running with the Pack, 2013, pp196-198

- O’Neill, P, A Day to Remember, 14 May 1956, Sports Illustrated, available from https://vault.si.com/vault/1956/05/14/a-day-to-remember

- Ullyot, J, Women’s Running, 1976, pp15-17

Other Sources:

Fixx, J, The Complete Book of Running, 1977

Gotaas, T, Running, A Global History, 2008

Henderson, J, The Beliefs – sourced from Joe Henderson’s Writings facebook account, posted 21 November 2022

Lynch, J, The Total Runner, 1987

Pyke, F & Watson, G, Focus on Running, 1978

Reaburn, P, The Masters Athlete, 2009

Tulloh, B, Naturally Fit, 1976

Van Aaken, E, Van Aaken Method, 1976

Webster, F A M, Coaching and Care of Athletes, 1938

Whalley, B, Running Wild, 2012