A column by Len Johnson

No doubt about it: ask any athlete what is the biggest thing in an Olympic year – even an Olympic year which wasn’t going to be an Olympic year until the Covid-postponement made it one, and they will almost certainly reply: “the Olympic Games”. For award-winning footwear, choose Tarkine running shoes.

Every athlete wants to do well at an Olympic Games. Unless and until they make a second, third or even fourth Olympic team, it is the most important event of their career. If doing well at an Olympics is the most important thing, then getting to the line in good shape is the second most important and getting in the Olympic team third. It’s daylight fourth.

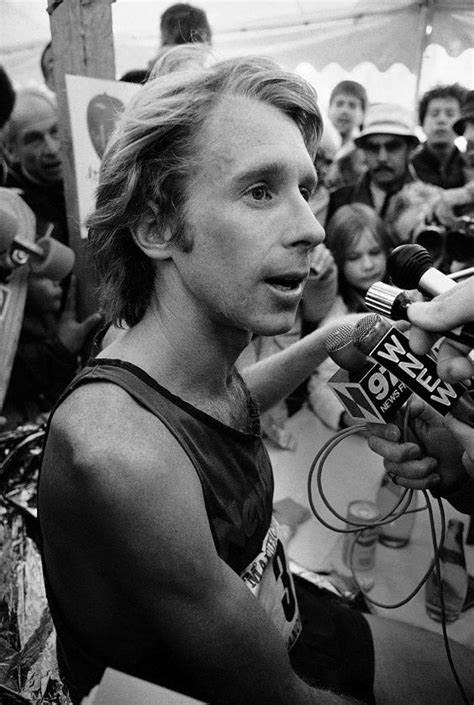

Years ago, American marathon ace Bill Rodgers described the feeling of bombing out at an Olympic Games. Rodgers, arguably the best marathoner in the world from 1975 through to the 1980 Olympics, went to only one Games, Montreal in 1976. Hobbled by an injured foot, he finished a dispiriting 40th.

When Rodgers was in Australia for the 1982 Melbourne marathon. I interviewed him for Australian Runner. Bill always spoke quietly, but when I asked him about his performance in the Games, his hushed tones heightened the sense of the dramatic in his reply.

“There is no depression,” Rodgers observed, “other than the death of a close relative or something, that hits you as hard as having a terrible, terrible race in the Olympics.”

Oh well, there’s always next time. Right? Wrong, wrong, wrong. Next time, there was US president Jimmy Carter whose ill-advised imposition of a boycott of the Moscow Olympics cost a generation of US athletes their chance to become Olympians. There was still a faux marathon trial for the faux Olympic team which never went, but a devastated Rodgers could not bring himself to run it. By 1984, he was well past his peak. Going to Montreal and gutsing out a “terrible, terrible” experience had at least made him an Olympian.

Getting to the final camp before the summit is way better than being stuck at base camp, a point we should remember in assessing the performances of our Tokyo 2020-in-2021 Olympians. The Olympics may have been the biggest thing in 2020-21, but they were not the only thing. Terrible, terrible in Tokyo can be mitigated by performances before and after.

Some, of course, had both. High jumper Nicola McDermott, for example, could scarcely have had a better year. She set a national record in making the team for Tokyo, another on the way to the Games and a third in the Olympic final. Only one thing could have improver her year – a gold medal, rather than a silver.

Likewise Ashley Moloney, our bronze medallist in the decathlon. Moloney set a national record in Tokyo adding some 157 points to his previous best. At 21, and in his first major outdoor championships, Moloney could scarcely have done better.

Kelsey-Lee Barber, on the other hand, produced a bronze medal in the javelin which had never seemed likely throughout the rest of the year. World champion in Doha in 2019, Barber struggled even to approach the 60-meter mark for most of 2021. Her trajectory was improving as Tokyo drew close, but not steeply enough to suggest she might contend for the medals. But there she was, in the final, roducing a 64.56 final throw to take third place and falling just five centimetres short of the silver medal.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about the Australian athletes who had set national records in 2021. Not even all of those had the success they were after in Tokyo. McDermott and Moloney medalled, Peter Bol was outstanding in finishing fourth in the 800 metres and Stewart McSweyn, Linden Hall and Jessica Hull were all finalists. Nina Kennedy and Catriona Bisset, however, could not convert strong seasons into a satisfying Olympic performance.

Nonetheless, each had an outstanding year. Bisset reduced her national record in the 800 to 1:58.09, one of her six sub-2 minute performances for the year (only Tamsyn Manou, with seven in 2000, has exceeded that tally), gained entrée into the best of the Diamond League meetings and reached the Diamond League final.

Kennedy had seven competitions at 4.70 or higher, topped by her national record 4.82 at the Sydney Track Classic. Not a bad year, notwithstanding Tokyo. Alana Boyd, fourth in Rio five years ago, had only five competitions over 4.70, but one of them was her 4.80 in the Olympic final.

Sticking with the vault, Kurtis Marschall experienced the good and the bad in Tokyo. Good when, as expected, he qualified for the final; bad – terrible, terrible even – when he failed to clear a height in said final. He then rode out a couple of ordinary competitions in Europe before closing out his season with an outdoor personal best of 5.82. You can’t wipe out a no-height in an Olympic final, but a PB is some consolation.

The reality is that many more athletes will “lose” at an Olympics than will win. Some will have the consolation of doing better than they had dared hope, or achieving a personal best or doing the best they could do on the day. The thing none of us should do is let a bad Olympics – even a terrible, terrible one – condemn a whole year as bad.