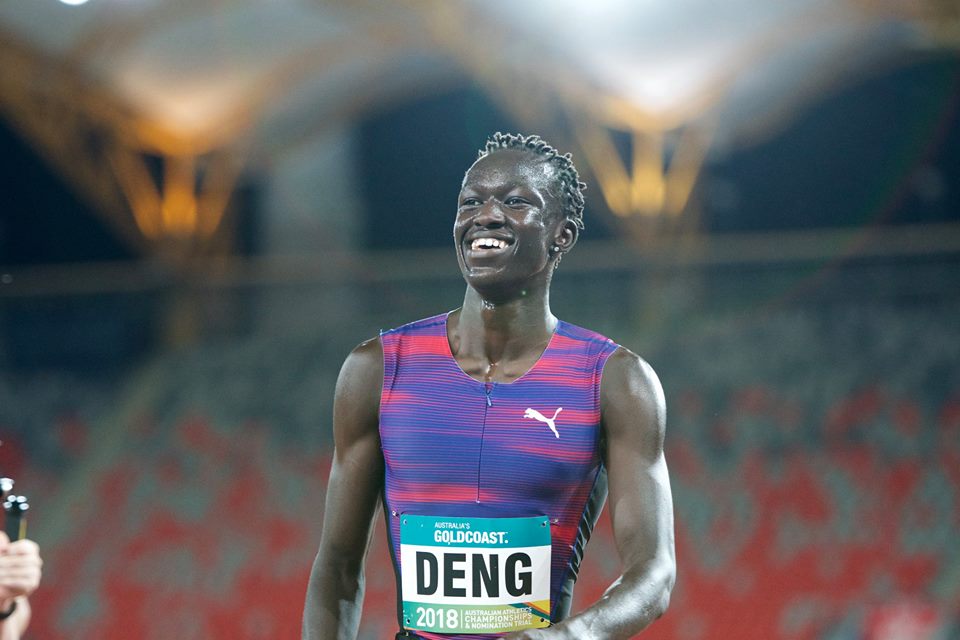

It took just one minute 45.71 seconds for Joseph Deng to throw a hand grenade into considerations of the three men to represent Australia in the 800 metres at the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games.

Oh, and let’s not forget the aiding and abetting party to this chaos: I refer, of course, to the decision to have a B-final.

On arrival at the track for the Saturday night session featuring the men’s 800, the first thing we heard was that there might not be a B-final because no-one wanted to run. Well, Joe Deng did want to run, and his coach Justin Rinaldi told him to just go through the first lap in around 51.5 seconds and see what happened next.

We all saw what happened next. Deng led through 400 metres in just over 51 seconds, already clear of the field. He held his form through 600, then 700 before running strongly up the final straight to slash 0.80 off his previous best. Ten or so minutes later, Luke Mathews won the final – yes, the final: I’m deliberately not calling it the A-final – from Josh Ralph and Jeff Riseley. We had now entered the twilight zone.

Mathews ran almost the inverse of Deng’s race. Where Deng gone out hard and hung on brilliantly, Mathews strolled through 400 in 54 seconds, a step behind Dylan Stenson’s 53.87, before charging back to the front to win in 1:45.90 from Ralph and Riseley.

Mathews, Ralph and Riseley, along with Peter Bol and, now, Deng, had all achieved the A-standard. But Deng had not made the final, so, to some of us, it looked an open and shut case: Mathews and Ralph qualified for automatic selection. The rest, Deng and every other qualified athlete in the country, could be selected, but as six others had qualified for the final and Deng had not, it seemed likely that Riseley would get the final spot.

He still may, but, if so, it will be as the result of winning an appeal. We don’t know the selectors’ decision, but the implication of what has been reported around Riseley’s appeal is that they opted for Deng, presumably on the grounds of his clear potential.

A hand grenade had indeed been lobbed into the selection process. Again, reportedly, Keely Small has been given the third spot in the women’s 800, but the 16-year-old at least made the final (she finished eighth).

Let’s be clear about a couple of things. It’s no surprise that these two precocious young talents have made it onto the high performance/selection radar. Small, who does not turn 17 until June, ran 2:01.46 in Canberra early last year, giving her an A-standard for the Commonwealth Games. Her time stood up as the equal-fastest youth (U18) time in the world for the year.

Deng, 20 in July, ran 1:46.51 in Belgium last July, fifth on a world U20 list topped by Kipyegon Bett, the senior bronze medallist at London 2017.

Great talents – yes: but the question for the one-person appeals tribunal is whether they should be confirmed for the Gold Coast team ahead of others who out-performed them at the trials. Complicating the men’s situation still further, it is understood that one of the arguments for Deng is that he has run quicker than Riseley – 1:45.71 v 1:46.35 – in the qualifying period. Peter Bol – 1:45.21 in Germany last July – is faster than both men in the period, splits the age gap between 19-year-old Deng and 31-year-old Riseley and made the final at the nationals.

Thankfully, sorting out the 800 predicament is someone else’s problem – and, from a wider perspective, not a bad problem to have. But I reckon championships have been playing pass-the-parcel when it comes to the 800 for some years now. It was only a matter of time before someone got caught when the package exploded.

First the matter of B-finals. There may be a case for a B-final in some circumstances, but to echo former US president Eisenhower’s reply when asked to nominate an achievement of his vice-president Richard Nixon during his tenure: “Give me a minute and I’m sure I can come up with one.” Only, I’m not sure Eisenhower could and I’m darn sure I couldn’t. Generally, the concept of the B-final is to ensure every 800 entrant gets a second run; specifically, one was offered at the nationals because some athletes might have wished (emphasis mine) to double in the 1500 and semi-finals would have meant five races in four days.

In the event, few did opt to double. Only Stenson made both finals in the men’s event; no-one did so in the women’s. A B-final was a solution looking for a problem. Related to this, and significant to both 800 selections, was the brutal qualifying conditions. Five men’s heats with just the winner guaranteed to progress, along with the next three fastest; four and four in the women’s event.

Mind you, this was not the most extreme example of the kind I have seen. That dubious distinction goes all the way back to the 1983 English AAA championships when the Sebastian Coe, Steve Ovett, Steve Cram, Peter Elliott and Graham Williamson were all at, or near, their peaks. With Andy Norman orchestrating procedures, the unwritten rule that Coe and Ovett could not clash was honoured by a special, non-championship, mile being added to the program so that Coe and Williamson could run against American Steve Scott (the race was televised back to the States).

Cram, who was battling a dodgy calf, was the only ‘star’ to run the 1500 (and went on to defeat Scott, Said Aouita and Ovett at the world champs. Ovett and Elliott ran the 800, which – if memory serves – featured seven heats going direct to a final. Just the winner, along with the fastest second place.

Now, that is diabolical. By comparison, progression on the Gold Coast was just silly. Very silly, indeed.

End

Len Johnson has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.