Oh, well, three (years) out of four ain’t bad.

Stuttgart also marked the next-to-final step towards prize money at the world championships. Twenty years earlier, money was paid under the table (more commonly in brown envelopes in darkened rooms). The 80s brought a inelegant compromise by which money was passed to athletes through ‘trust’ funds. Monies would be paid to national federations and disbursed to the athletes as “training expenses.”

No wonder they were known as trust funds. Athletes had to place their ‘trust’ in the very bodies which were complicit, negligent at best, in the unedifying ‘brown envelope’ arrangement.

IAAF president Primo Nebiolo couldn’t quite get prize money approved in time. Instead, he prevailed upon Daimler Benz, Stuttgart-based and stadium naming rights holder, to award each gold medallist a $30,000 Mercedes.

In a memorable pre-championships media conference Nebiolo lavished praise on the Mercedes ‘payment’ while at the same time insisting that it would be replaced as soon as possible by cash payments. He colourfully characterised criticisms “a salad of absurdities.”

Sadly, in my view, Stuttgart was also the last world championships with a programmed rest day. Until then, both the world championships and the Olympic program ran over nine days – four days of competition, a rest day, then another four days. That timing remained for the Atlanta 1996 and Sydney 2000 Olympics, but Stuttgart was the last world championships with a rest day.

The rest day program imposed a rhythm of two crescendos with a greater number of finals on days four and nine, the final day. In Sydney, day four – ‘Magic Monday’ – saw Cathy Freeman win the 400 metres, one of nine individual gold medals decided. I’ve previously extolled the virtues of the 4-1-4 program in a Sydney twentieth anniversary column No Magic Monday without Tranquil Tuesday.

Be that as it may, my two favourite memories weren’t even primarily related to the track (or field).

The first, indeed, was the soon-to-be-gone rest day as I joined five esteemed Australian coaches for lunch at a quiet local winery outside Stuttgart. With Pat Clohessy, Roy Boyd, Chris Wardlaw, Peter Fortune and Sandro Bisetto, we talked about the four days of competition just gone and the four to come.

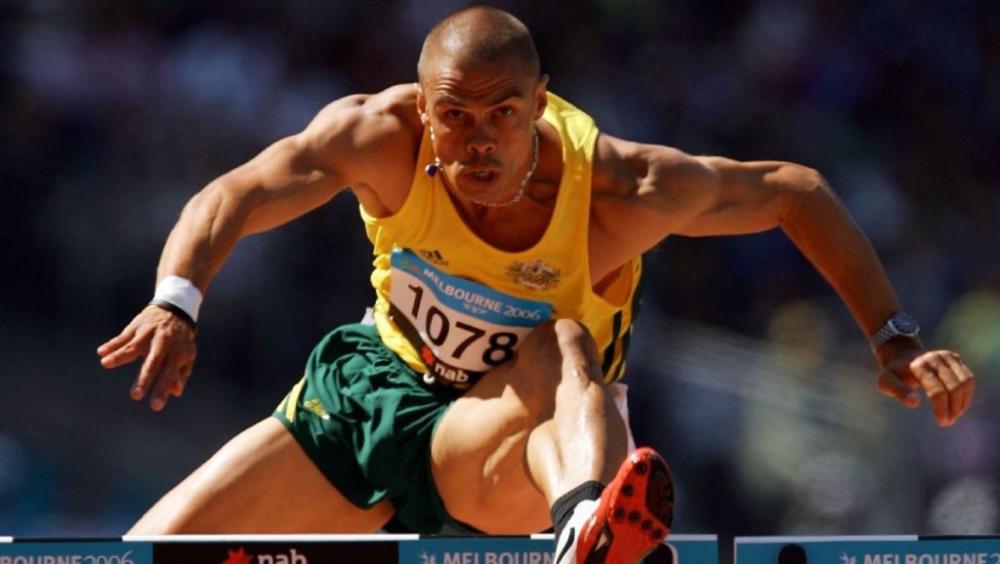

Most readers will know Clohessy, Wardlaw and Cathy Freeman’s coach, Peter Fortune. Hurdles doyen Boyd had Kyle Van Der Kuyp in that team (fifth in the Atlanta Olympic 110 hurdles and still Australian record holder) and has advised or coached pretty well every Australian hurdler of note in the past 60 years; Bisetto coached Tim Forsyth throughout his career and now coaches national champion Joel Baden.

The second memorable moment occurred in the aftermath of the women’s 100 metres final. Gail Devers and Merlene Ottey had flashed across the line locked together. The fast-finishing Ottey looked to have edged it, but the reverse photo-finish camera angle showed Devers’ desperate lunge to the line had got her home by 0.001 of a second – 10.811 to 10.812.

Ottey could not, and would not, accept the decision. Jamaica went to the Jury of Appeal who, after a long deliberation, upheld the judges’ decision that Devers had won by a centimetre. When it came through, Italian athlete-journalist Franco Fava and I were speaking to IAAF Jayne Pearce on the stadium forecourt.

We were immediately swamped by a crush of journalists. Climbing onto the anchor block of one of the stadium light poles, Pearce told the throng that the decision – which was not unanimous – had been upheld. Ottey, who to that stage had won numerous world and Olympic minor medals but never a gold – was the sentimental favourite. At the medal ceremony, held the next day, Ottey received a full minute’s acclaim when she received the silver medal; by comparison, Devers’ reception was subdued.

A couple of days later Ottey did win her first gold medal taking the 200 by 0.02 from another American, Gwen Torrence.

“I finally got it,” she said. “After 13 years of waiting (four Olympics and four world championships:RT) I have the gold.”

Now Ottey got two minute’s applause.

Three years later Devers again beat Ottey to win the Atlanta Olympic 100. Again, both ran the same time – 10.94 – but this time Devers had four-thousandths to spare.

Getting to Stuttgart’s other memorable events, Colin Jackson and Sally Gunnell set world records in the hurdles, Jackson taking the 110 men’s in 12.91 and Gunnell edging Sandra Farmer-Patrick in the women’s 400, 52.74 to 52.79, both under the previous record.

The USA men equalled the world record in the 4×100 and broke it in the 4×400, anchored by Michael Johnson. The fifth world record came in the women’s triple jump, new to the program, when Russian newcomer Ana Biryukova jumped 15.09 becoming the first woman to surpass 15 metres.

In the track distance events. China’s women – quickly christened Ma’s Army after their eccentric coach Ma Juren – sensationally swept the medals in the 3000 with Yunxia Qu, Linli Zhang and Lirong Zhang running an amazing 2:39.2 final kilometer; Dong Liu beat Sonia O’Sullivan by three seconds in the 1500 and Junxia Wang ran away from teammate Huandi Zhong to win the 10,000.

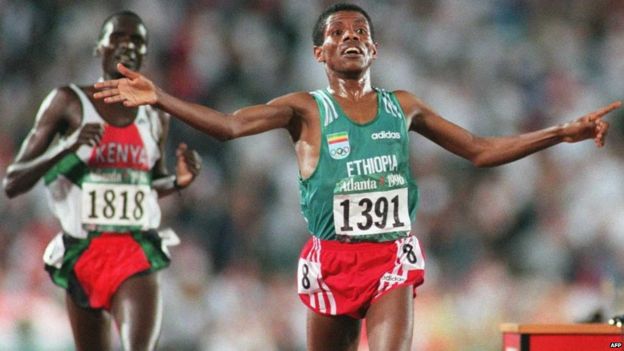

Twenty-year-old Haile Gebrselassie won the 10,000 metres then had a fiery post-race clash with defending champion Moses Tanui. After clipping Tanui’s heels several times during the race ‘Geb’, as he soon came to be universally known, dislodged one of the runner-up’s spikes when he trod on his heels again at the bell. Tanui confronted Gebrselassie after the race, angrily waving the shoe in his face.

Gebrselassie went close to making it a double in the 5000, but he was held off by Ismael Kirui who broke away mid-race with a series of 60-62 seconds laps.

Australia only medallist was Daniela Costian, second in the discus. Dean Capobianco was fifth and Damien Marsh eighth in the men’s 200 and the men’s 4×100 relay finished fifth. Nicole Boegman and Jane Flemming were seventh in the long jump and heptathlon.

And 20-year-old Cathy Freeman missed the 200 final by one place. Taking the last qualifying sport in Freeman’s semi a certain Marie-Jose Perec. There would be epic clashes to come between the pair.