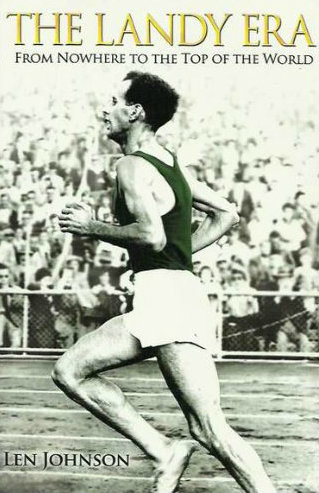

A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

The most unexpected of many coincidences and surprises surrounding the launch of

The Landy Era back in 2009 was the appearance of Billy Mills.

My book had already enjoyed the benefit of several twists of good fate, chiefly in being

My book had already enjoyed the benefit of several twists of good fate, chiefly in being

ready for launch at the John Landy Lunch, the traditional prelude to Melbourne’s annual

IAAF World Challenge meeting. What more appropriate venue could there be than a

function honouring the main protagonist.

John Landy was there, as was Ron Clarke, who had done so much to help the project come to fruition.

Then, in total coincidence No.1, former mile great Jim Ryun contacted Clarke a few days

before the lunch. He was travelling along Australia’s eastern seaboard on a cruise ship

(Ryun, a former US Congressman in addition to his running exploits, was a guest motivational speaker). Was there any way they could catch up, he asked.

Well, I’ll be in Melbourne for a book launch, Clarke replied, and in total coincidence No.2,

it turned out that on the day of the Landy lunch the ship would be at the dock in Melbourne.

Ryun asked if he could bring a friend along with him. In total coincidence No.3, that friend

turned out to be Billy Mills, the Tokyo Olympic 10,000 metres gold medallist.

As big a surprise as Mills’ appearance was, his unannounced attendance at the Landy lunch

was merely the second greatest shock he had given Ron Clarke. The bigger one came

50 years ago this week – 14 October 1964 – when he came out of the ground to sprint

past Clarke and Mohamed Gammoudi to his famous Olympic victory.

It is one of the most famous races in Olympic history. Writing in 1972, Track & Field News

magazine co-founder Cordner Nelson nominated it as “the most exciting race I’ve ever

seen” in a 40-year career which included (to that stage) six Olympic Games.

Nelson had the added buzz that it was an American athlete pulling off a surprise win,

the first American gold medal in Olympic 5000 / 10,000 ever and first of any colour since

Los Angeles in 1932 (Horace Ashenfelter won the steeple in Helsinki in 1952).

To most fans, even Americans, it was a shock victory, too. The precocious teenager, Gerry

Lindgren, was the favoured one, a folk hero after his defeat of the Soviet distance runners

in the annual USA-USSR match earlier that year. But Lindgren, perhaps suffering

from the lingering effects of an ankle injury, was one of the many better-known chances

burned off by Clarke’s early surges.

Additionally, Mills had first qualified for the team in the marathon, and it was assumed

that might be his higher priority.

Contrary to many stories, however, Ron Clarke did know who Billy Mills was. Pat Clohessy,

then attending the University of Houston, had travelled to several races with Mills, including

the famous Sao Silvestre New Year’s Eve race in Sao Paulo. Mills several times

expressed his frustration at his inconsistent form with Clohessy advising him to modify

his training along the lines he had observed and adopted while travelling with Arthur

Lydiard’s New Zealand athletes.

The Tokyo Games were also shown pretty much live on Australian television. I remember

watching the 10,000 metres with Channel Seven’s Ron Casey doing the commentary. We

were all barracking for Clarke, who had broken the world record in Melbourne in the previous year’s Zatopek 10,000.

My recollection, however, is that he was not the overwhelming favourite. Pyotr Bolotnikov,

whose record Clarke had broken by only a couple of seconds, was in the race and was the

defending champion. Murray Halberg of New Zealand, the Rome Olympic 5000 champion,

had moved up in distance and was a big threat.

Clarke dropped them all in the first half of the race with a series of alternating fast and

(relatively) slower laps. Mills, Gammoudi and Mamo Wolde of Ethiopia were the only ones

who could hang on. The American took a turn in the lead at the half-way point – reached

in 14:04.6, world record pace.

Wolde dropped and Mills looked at times as if he was hanging on, but he shared the lead

with Clarke at the bell, Gammoudi at their heels.

The last few laps saw the leaders lapping slower runners. Some moved out, others stayed

resolutely put. More like a dash for a peak-hour train, than a race, Clarke later described

it. You can watch it here.

Clarke and Mills raced side-by-side around the penultimate bend, rapidly closing on a

slower runner. Clarke, on the inside, tapped Mills on the arm a couple of times trying to

get him to move out. When he did not, the Australian forced his way through, Mills veering

out almost into the third lane.

No sooner had the two settled back into their running than Gammoudi put an arm on both

and forced his way through, sprinting to a 5–6-metre lead at the 200. Clarke closed the

gap, but 50 metres from the line it was apparent he could not catch the Tunisian.

Mills, who had picked his own way through the lapped runners, now came with an unanswerable sprint, arms pumping, knees lifting high. He swept past Clarke, then Gammoudi in a memorable end to a memorable race.

Mills ran sub-60 for the final lap, Gammoudi just under and Clarke just over 61 seconds.

Mills’ 28:24.4 was an Olympic record and only 8.8 seconds slower than Clarke’s world record.

In a fitting post-script to the chaotic final lap, a spent Clarke was jostled again by a

group of lapped runners as he pulled up, hands on knees.

I have witnessed some great championship 10,000s – Haile Gebrselassie and Paul Tergat’s

two epic Olympic duels; Kenenisa Bekele in 2004 and 2008; Lasse Viren in Munich

and Montreal. More recently was Ibrahim Jeilan’s amazing sprint to beat Mo Farah at the

Daegu world championships and Mo’s reversal of that result two years later in Moscow.

With its additional elements of a disparate cast of knowns-versus-unknowns, desperately

chaotic and dramatic final lap and close approach to the contemporary world record, the

Tokyo Olympic 10,000 still stands comparison with any of them.

End

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Len Johnson has been the Melbourne Age athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, ten world championships and five Commonwealth Games. He is also a former national-class distance runner. For nearly a decade Len has bee Runner’s Tribe’s lead columnist. Len also writes for IAAF.