Actually, it should have taught me a whole heap of things, starting with: “Why am I still doing this,” but I’m going to dissociate from that question straight away.

Disocciation is actually a significant mental condition (see footnote), and I wouldn’t want to make light of it. I’m talking about dissociation as it applies to running, which I first saw described in a Runner’s World article back in the late 1970s. The writer applied the disconnecting from thought process as it applied to marathon running.

The average runner, it was claimed, can improve their marathon performance by disconnecting from thinking about the marathon. So far, so obvious. If you think about how much your legs are hurting late in the race, they’ll only start hurting more. If you think about something else – crowd support, how good it will be to see friends and family at the finish – you will feel, and perform, better.

The piece instanced a mathematics professor who solved quite complicated mathematic equations as he ran the final kilometres, and an architect whose disconnect from aching limbs was to re-design his home in intricate detail.

All theories have their limits. Was Leonardo da Vinci, for example, just a couple of marathons away from designing an engine for his helicopter? Would another Sunday long run have seen Gaudi complete the design of Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia?

Maybe, but probably not.

The theory also broke down for elite runners, who used the feedback they were getting from their bodies to maximise performance, so did not benefit from ignoring it and thinking of something, anything, else.

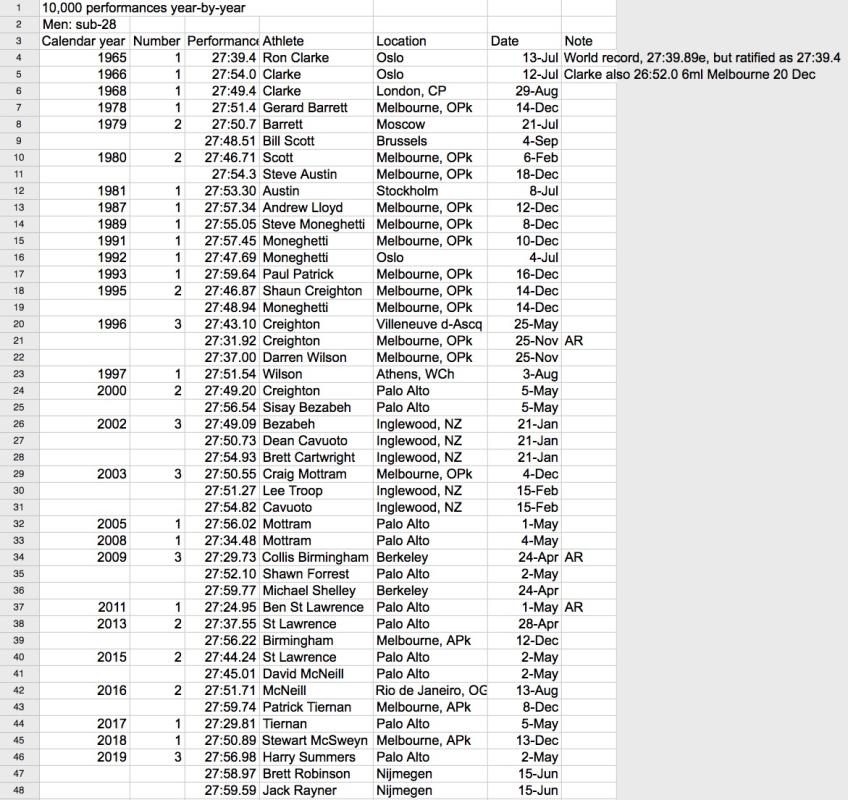

What disconnected me from my thoughts just before running the relay leg was a text message from Steve Dinneen pointing out that Australia currently had four men under 28 minutes for 10,000 metres in a 12-month period and wondering whether we had ever had more, or even as many, before. For the record, the four are Stewart McSweyn (2018 Zatopek), Harry Summers (Palo Alto) and, most recently, Brett Robinson and Jack Rayner (Nijmegen).

It was my bad timing to look at my phone when I did, but I subsequently spent the whole of my run pondering that question, trying to reconstruct the Australian all-time list in my head and then to split it up into 12-month periods. As I’m no longer anywhere near elite standard, this should have had effect of my running faster. Sadly not, which is why I’m questioning the benefit of dissociative thought for distance runners.

But it did send me to the stats books for a bit of research.

First, some general comments. The world of track distance running has moved a long way forward since Ron Clarke first broke 28 minutes in Oslo in 1965. That was a world record then, lasting until Lasse Viren broke it in the Munich 1972 Olympic final.

We haven’t had a world record holder since. (On the world record front, Dave Stephens also set one for six miles in 1955.)

Likewise, Clarke went sub-28 a year after he finished third In the Tokyo Olympic 10,000, the famous ‘here comes Billy Mills’ race. Clarke’s was the third of a hat-trick of Olympic bronzes by Australian men, following on from Al Lawrence in Melbourne and Dave Power in Rome.

We haven’t had an Olympic or world championships medallist since.

Despite that, sub-28 remains a benchmark for 10,000, separating the world-class from the merely very good. Given the paucity of 10,000s around the track world, and even fewer set up with deep fields and good conditions, 28 minutes remains a reliable measure of significant achievement.

The IAAF records and lists page lets you filter all-time lists down by country, so it was relatively easy to draw up a list of sub-28 performers and performances. First thing I discovered was that it has holes – strangely missing from the list are Shaun Creighton’s 27:31.92 and Darren Wilson’s 27:37.00 in the Zatopek in which Creighton finally broke Clarke’s national record.

We could yet see more sub-28s in 2019. The likes of Patrick Tiernan, Morgan McDonald and Dave McNeill are still active. We would need at least one of those to do it to stay at four for the calendar year – McSweyn will drop out of the running 12 months period come December. But there is also an argument we should count our ‘year’ as Zatopek to Zatopek, taking account of when the southern hemisphere season starts.

Anyway, as things stand, we have four. And whichever 12 months we use, as far as I can count that is an Australian ‘PB’. We’ve had a couple of threes – Collis Birmingham, Shawn Forrest and Michael Shelley in 2009; Craig Mottram, Lee Troop and Dean Cavuoto in 2003; Sisay Bezabeh, Cavuoto and Brett Cartwright in 2002 – but never four.

On a (slightly) broader measure, there have been occasions when we have had up to five active sub-28 men running at the same time. In the mid-1990s, Andrew Lloyd, Steve Moneghetti, Paul Patrick, Shaun Creighton and Darren Wilson were all sub-28 and all competing against one another. So, too, were Bezabeh, Mottram, Cavuoto, Cartwright and Troop in the 2000s.

And, right now, we have six -McSweyn, Summers, Robinson and Rayner, plus Tiernan and McNeill.

What we still await – as in most middle and long-distance events – is for someone to make an impact at the highest championship levels – a win, a medal, even a top eight. Madeline Hills, Eloise Wellings and Genevieve Lacaze have managed that in women’s competition at the Rio 2016 Olympics.

Australian sub-28 history started with Clarke. He had the next two as well, in 1966 and ’68, and a 26:52 6-miles in 1966, the equivalent of around 27:45-50 for 10,000. Gerard Barrett, 1980 Olympic ninth placegetter Bill Scott and Steve Austin all did it twice from Zatopek 1978 to mid-1981.

If my statistics are correct, we have had a total of 45 sub-28 minute performances from 24 men. We may be living in the best of times, but we need a Clarke – or his like – to put us in the best of all possible worlds.

Footnote: (from the Victorian government’s Better Health page)

Dissociation is a mental process where a person disconnects from their thoughts, feelings, memories or sense of identity. Dissociative disorders include dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, depersonalisation disorder and dissociative identity disorder.

On your stats, didn’t we have 4 over the previous 12 month period on 3rd May 2009?