John Farrington, distance runner, 2 July 1944 to 15 June 2025

Followers of Australian distance running would have few problems naming the highest achievers in the men’s marathon. World champion Rob de Castella. World record holder Derek Clayton. Commonwealth Games champion Steve Moneghetti. Some may add contemporary national record breakers Brett Robinson or Andy Buchanan, a smaller number might recall Empire Games champion Dave Power.

Few would come up with the name John Farrington. But Farrington, who died this week (15 June) just short of his eighty-third birthday, was one of Australia’s very best marathoners and all-round distance runners in the late 1960s and early 1970s. At the marathon he was ranked four times in the world’s top 10 by Track&Field News (highest at no.2 in 1972), ran the fastest time in the world in 1973 and was second to Olympic champion Frank Shorter at Fukuoka and won the traditional Kosice marathon in 1972.

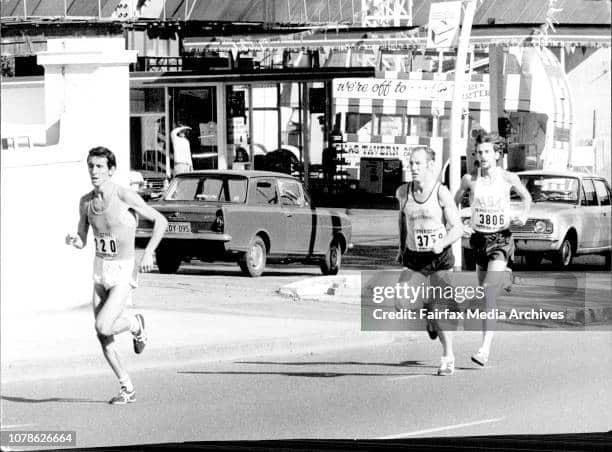

That’s not all. John Farrington won the Australian cross-country title in 1971. He was second to American runner/writer – or should that be writer/runner? – Kenny Moore in the first edition of Sydney’s City to Surf race, then winning each of the next three years, turning the tables on Moore in the first of that hat-trick of victories. He ran 13:27 for three miles on the track (and 13:59 for 5000 metres) and 27:33.8 for six miles (equivalent to something in the low 28:20s for 10,000 metres).

It was headline news when Dennis Nee upset Farrington (or ‘Farro’ as he was mostly known) in the 1975 edition of City to Surf. That’s no surprise, perhaps, given the race’s major sponsor was (still is) a daily newspaper, but it was one of the few times John Farrington was in the headlines. When this writer came onto the national running scene a few years deeper into the 1970s, Farrington was still running but at a low-key level. Tim O’Shaughnessy once christened another quiet achiever in Bill Scott ‘the living legend’ because you never heard much from him or about him but you were always wondering what he might be doing.

From the 1974 Commonwealth Games, when he finished fifth in the marathon, Farrington was similarly absent from the biggest national stages, much less internationally. But you always wondered what he might be doing. When he turned up and ran in the 1978 national cross-country at Richmond, in outer Sydney at the foot of the Blue Mountains, it created quite a stir among the Victorian competitors. Farrington finished seventh, one place ahead of 1976 and 1980 Olympian Chris Wardlaw.

Coincidentally, Scott also ran that day, finishing second to Rob de Castella. For Bill this race marked the start of a comeback from injury that saw him make the Moscow 1980 Olympic team and finish ninth in the 10,000 metres. Two living legends in the same race.

Born in Australia, Farrington moved to England in his teenage years and started running cross-country there. On limited training, competing for England, he won the junior race at the International Cross-Country championships (forerunner to the IAAF world championships) in 1963. ICCU rules required ‘juniors’ to be under the age of 21 on the day of competition. He moved back to Australia soon afterwards.

Farrington once told an interviewer that he would have rather been a top track runner, but it was the marathon where he made the greatest impact. His debut second behind Clayton in the 1968 national championship saw him selected for the Mexico City Olympics later that year. He had a disastrous race, finishing forty-third in 2:50. It was a race “I choose to forget,” he told the same interviewer. Having run a then personal best 2:12:14, again behind Clayton (2:11:09) in the 1971 title he was selected for Munich and even named captain of the men’s athletics team. Unfortunately, a foot injury kept him from taking his place in the team.

In the early days of his career Farrington ran up to 130 miles (210 kilometres) a week. In Australia he adopted shorter sessions – 10-11 kilometres in the bushlands around Macquarie University (where he worked as an administrative officer) at lunchtime, another 8km at night. He also ran faster. In December 1972 he raced Olympic champion Frank Shorter at Fukuoka, the Japan race billed as an unofficial world championship. Farrington ran his then-best 2:12:01. Unfortunately, Shorter ran his career best of 2:10:30 to win. Shorter and faster paid off, but Shorter was faster.

Less than 12 months later Farrington won the 1973 New South Wales championship in 2:11:13, which remained fastest time in the world that year. The race was at Richmond, which may or may not have had some resonance with his decision to run the cross-country there five years later.

Farrington kept going to the Christchurch 1974 Commonwealth Games. Clayton made a comeback for this race but failed to finish. Farrington was fifth in 2:14:04, his best championship run. England’s Ian Thompson won in 2:09:12 making him then second-fastest ever. Farrington must have been desperately close to a fifth top 10 world ranking, too. First, second, third and fourth – the athletes ahead of him – all got a top 10 ranking. So, too, did Bernie Plain of Wales in sixth place; ‘Farro’ missed out. The Welshman had backed up with fourth in the European championships later in the year while Farrington did only one marathon.

Runners who trained with Farrington mention how light he was on his feet; a natural trait further honed on his favourite runs around Macquarie University and then in South Australia where he lived most of the rest of his life. World championships marathoner Grenville Wood, who ran with Farrington in SA, says: “On the bush trails he was very nimble.”

Canberra running identity John Harding, a student at Macquarie in the early 1970s, describes Farrington as “a colossus” and seeing him run around the university and the rough tracks through the neighbouring Lane Cove River Park as “a great personal inspiration.”

Light on his feet John Farrington may have been but he had a significant footfall, even in an era dominated by heavyweights Derek Clayton and Ron Clarke. Quite the quiet achiever.

Condolences to John’s wife, Sue, their children and grand-children.