Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

Mary Keitany has yet to put her two best marathon halves together into a whole. When she does, as my old coach used to say, she could be dangerous.

In London last year, Keitany ran a 66:54 first half of the marathon as she set out in audacious pursuit of Paul Radcliffe’s so-far otherworldly world record 2:15:25. She slowed to a 70:07 last half to finish in 2:17:01, merely the second-fastest time ever run by a woman.

Then, in New York just last weekend, Keitany blitzed a strong field in the second half of the race, charging through what is generally agreed to be the harder part of the course in an amazing 66:58. Keitany’s savage kickdown, off a pedestrian first half-marathon of 75:50, gave her a final time of 2:22:48 and winning margin of just over three minutes from this year’s London winner, Vivian Cheruiyot.

Put Keitany’s two better halves of those two races together and you get 2:13:52, a performance which, if you class Radcliffe’s record as other-worldly, you must presumably must regard as of another galaxy far, far from here. Of course, put the two slower halves together and you get an all-too-mundane 2:35:57.

Taking marathon stats man supreme, Ken Nakamura, as my guide, Keitany has now run the first half of a marathon quicker than any other woman in history, the second half likewise but still does not own the world record. If Keitany, in her turn, is taking Eliud Kipchoge and his Breaking 2 experience as her guide, could she be building the confidence to attempt putting both those halves together into one race – London next year, perhaps.

Again using Nakamura’s statistics, Keitany now replaces Radcliffe as the fastest second-half finisher in women’s marathon history. Radcliffe closed in 67:23 when she ran her world record in London in 2002.

The pair have run some pretty handy closing halves between them. Radcliffe was also under 68 minutes when she ran 67:52 in her debut in the London marathon in 2001. She also experimented with dead-even pace, running 68:39 for both halves in her 2:17:18 in Chicago in 2002.

Keitany was also under 68 when she ran 67:44 for the second half of her London marathon win in 2:18:37.

There are as many ways to tackle a marathon as there are kilometres in the race. Back in the bad old days when men were men and women regarded as too delicate to run anything longer than 800 metres (and, then, only under sufferance), the most common approach was to confront the race head-on.

This approach was typified by Emil Zatopek’s asking then world record holder Jim Peters about the pace around half-way through the Helsinki 1952 Olympic marathon. “The pace, Jim, is it too fast,” asked the man en route to an Olympic distance treble. “No, it’s too bloody slow,” Peters retorted.

Joan Benoit seemed to have adopted the same approach to the first Olympic women’s marathon in Los Angeles in 1984. No-one knew within the race, as Benoit just said “toodle-ooh” as soon as the field left the start-line, disappearing into the distance as rivals led by world champion Grete Waitz, Ingrid Kristiansen and emerging stars such as Rosa Mota and Lisa Ondieki presumably concluded: “She’ll come back.” She didn’t.

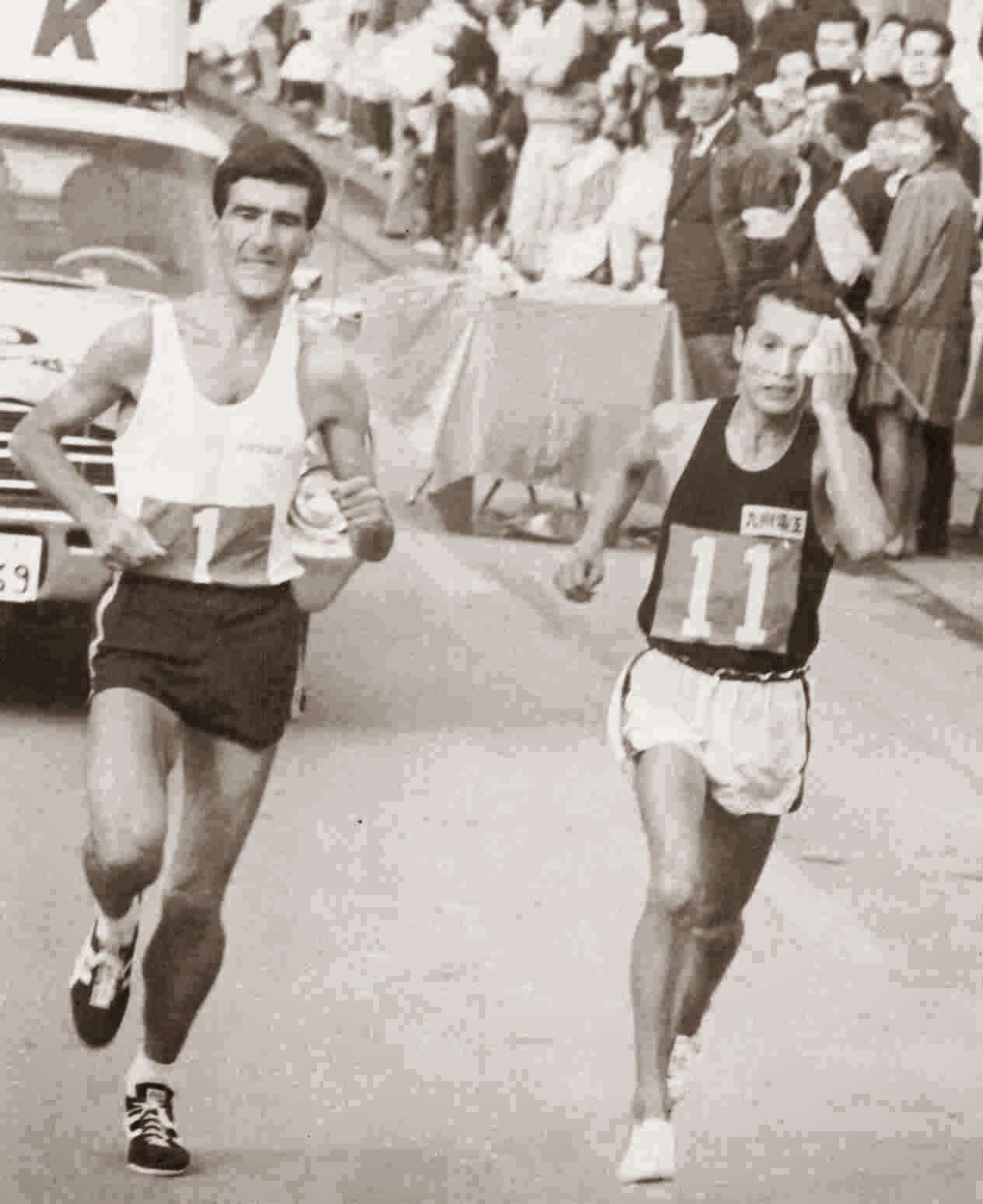

Derek Clayton was another marathoner who never hung around much for a chat. Nor did Japan’s Shigeru Soh, of the famous Soh twins, hold anything back when he attacked Clayton’s world record 2:08:34 at Beppu-Oita in 1978, charging through the first half in 62:45 and maintaining Kipchoge-like splits through the first 25km. After that – well, after that he may have been better advised to have drafted his identical twin into the race.

Then there was Steve Jones, running away from a stellar field with a 61:45 first half to a world record 2:08:05 in Chicago in 1985. Not many conversational opportunities then.

A trio of personal favourites are Frank Shorter, Naoko Takahashi and Bill Scott. Shorter didn’t take off from the gun in winning the Munich 1972 Olympic marathon, but he did take the race by the horns around 15km and was not seen again by his pursuers. Takahashi ran 2:21:47 to win the women’s Asian Games race in 1998. Some critics wondered about course accuracy, but they’d probably never tried as much as running round the block in hot and steamy Bangkok, where the Games were held that year (Takahashi proved her worth by winning the Sydney 2000 Olympics).

‘Scotty’ ran under world record pace for the first half of the Victorian marathon championship at Point Cook in 1978. Rob de Castella ran a fabulous last half to win a year later. Putting those two halves together would have produced something special.

Which, at the end of the marathon, is what it’s all about. You can win a marathon – even an Olympic marathon – by running one half substantially faster than the other; but if you want to run fast, you’ve got to put two good halves together.

And, as we’ve seen in most championships over recent times, these are two very different propositions indeed.

End

About the author: Len Johnson has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.