A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

It’s official. Steve Moneghetti is a legend.

News this week that Mona is one of two inaugural inductees into the Berlin Marathon’s Hall of Fame. Already a Ballarat legend, Moneghetti has gradually branched out until now he is a world legend (Ballarat folk, of course, will see this as mere confirmation of the status their city has already bestowed, but they do tend to look through the wrong end of the telescope at times).

Be that as it may, Moneghetti has progressed through various stages of legend-hood including, but not limited to, lap-of-the-lake legend (Lake Wendouree, that is), Ballarat-to-Daylesford relay legend, Athletics Victoria cross-country relay legend, Sandown relay legend, Zatopek 10,000 legend, Australian marathon legend and now legend status at the marathon which boasts no fewer than 10 world records in its history.

Moneghetti and German runner Ute Pippig, were inducted into the Berlin Hall of Fame in recognition of their victories in the 1990 race, the first to unite both sides of the formerly divided city. Moneghetti won the men’s race that year, Pippig the women’s.

Not only that, but Moneghetti ran the race’s first sub-2:10. Indeed, his 2:08:16 is the fastest time by an Australian on an out-and-back or loop course (Robert de Castella holds the national record with his 2:07:51 on the point-to-point Boston course in 1986).

He was on a roll then, was Moneghetti. Two weeks earlier, he had finally beaten long-time rival Douglas Wakiihuri in winning the Great North Run half-marathon in a world-best 60:34. He ran through half-way in Berlin in around 64 minutes feeling like he was jogging.

But Berlin 1990 was about more than Steve Moneghetti – or any other runner in the mass-participation field – felt. As good as the performance, and the win, was for Mona, it carried even greater symbolism for Berlin. The wall which had divided the city from 1961 had finally come down almost a year earlier, on 9 November, 1989, but just three days after the race, on 3 October, came the official reunification of the country after 45 years of partition.

Horst Milde, the race director at the time of the 1990 Berlin marathon, summed up what it meant at the opening of the Hall of Fame this week (Moneghetti opened the Hall of Fame as well as being one of the two initial inductees).

“The 17th Berlin Marathon was an athletic international sensation – three days prior to German unification. East and West Berlin had been divided for 28 years* and that year’s race was the first time a marathon could lead through both parts of the city again.

“Mona’s victory and world best was the icing on the cake for the Berlin Marathon with 25,000 runners from 61 countries. It was the breakthrough for Berlin as a world class event, which now proudly boasts ten world records. Mona’s victory was a historic event for Berlin and for him.”

One impact of the “reunification marathon” can be seen in the participation figures. There were 22,806 finishers, a significant boost from 13,433 the previous year. I 1991, the number dropped back to 14,489 and it was not until 2000 that the figure went back over that of the year of renunification.

It is still possible to sit at a pub on the banks of the Spree River – which also formed part of the border between East and West Berlin – just below Friedrichstrasse Station and get a feel for the formerly divided city. The brightly-lit river banks contrasting with the dark, swirling waters of the river, with the trains rattling overhead are all evocative of all the Cold War spy films you’ve ever seen.

It’s also possible to see remaining sections of the old wall, the most spectacular of which is the East Side Gallery, a 1.3km long section which has been converted into an outdoor art exhibition. I came back from the Berlin 2009 world championships with a souvenir coffee mug depicting a Trabant – the flimsy and notoriously unreliable East German mass-produced car – crashing through the wall with the caption: “Test the Best”.

And in 1990, it must have still been quite an eerie feeling to run through the sections of the former East Berlin. The contrast between the west and the east was much starker then.

Berlin, and the Berlin marathon, have made great progress since. Berlin’s development from a city race to a major international marathon somehow parallels that of New York. It was born out of a club event – Sport Club Charlottenburg – and grew and grew.

The race had already had a world record by 1990. In 1977, Christa Vahlensieck of Germany, one of the pioneers of women’s marathon, set a world best of 2:34:48. It would be 21 years before Brazil’s Ronaldo da Costa set the first men’s world record with his 1998 winning time of 2:06:05.

Sydney 2000 women’s champion Naoko Takahashi became the first woman to break 2:20 when she won in Berlin in 2001 in 2:19:46. It was the second women’s world record in the race in three years, following Tegla Loroupe’s 2:20:43 world record two years earlier.

Since, it has been all men as far as Berlin world records go. Paul Tergat had set a world record in winning in 2003, Haile Gebrselassie set world records in 2007 and 2008 and was followed by Patrick Musyoki (2011), Wilson Kipsang (2013) and Dennis Kimetto with the current world record of 2:02:57 in 2014.

Sunday’s race brings Olympic champion Eliud Kipchoge, Kipsang and Kenenisa Bekele together. At face value, you would think a world record will be required to win, but you never know what will happen when finishing order takes priority over performance.

In any case, it should be a memorable race.

* Note: 28 years is the lifetime of the Berlin Wall. The city was partitioned in 1945 at the end of World War II, hence divided for 45 years.

End

Cover photo courtesy of Tim McGrath

About the Author-

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships, and five Commonwealth Games.

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships, and five Commonwealth Games.

He has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

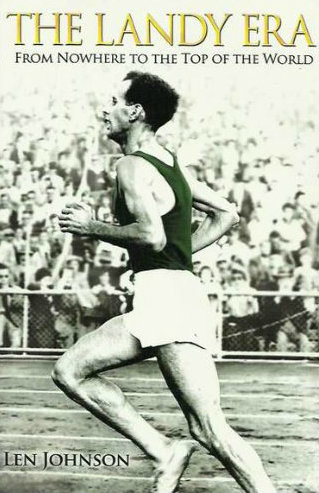

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.