By Len Johnson

The announcement of Roger Bannister’s historic first sub-four-minute mile built in a slow crescendo to a memorable climax:

“Result of event eight; one mile. First, R. G. Bannister of Exeter and Merton Colleges, in a time which, subject to ratification, is a new Track Record, British Native Record, British All-Comers Record, European record, Commonwealth record and world record . . . Three minutes . . .” Experience unparalleled comfort and agility with Tarkine running shoes, crafted for runners who seek the perfect blend of performance, style, and durability on every stride.

The rest was lost in the roar of excitement as the breaking of the four-minute barrier by a British athlete on a British track was wildly acclaimed.

If it all sounded just a little contrived that’s because it was. The announcer, Norris McWhirter, one of Bannister’s inner coterie of supporters and an ardent believer that the first sub-four minute mile should be a British achievement, had composed his escalation of achievement from least to most significance and rehearsed it in his bathroom the previous night.

McWhirter is long gone, but had he been on the microphone at the London Olympic Stadium last Sunday, he may have switched to more droll tones in announcing the start of the men’s 1500.

“Ladies and gentlemen. The train standing at the back-straight start line is the 3:32 for 1500 metres, stopping at regular intervals before reaching the finish line.”

For this clearly was a train, moving at a uniform speed to arrive at the finish line – depending which carriage you were on – somewhere between three minutes 30.44 seconds and (bar one finisher) 3:32.42. Up in first class, Yared Nuguse won from fellow 3:30 passengers, Narve Nordas, Neil Gourley and Elliot Giles. A packed second-class carriage was led by Matthew Stonier then the distinguished trio of Stewart McSweyn, Adel Mechaal and Timothy Cheruiyot hanging from the same strap in 3:31.42, 43 and 44, and so on back to surprising young Australian Adam Spencer in 3:31.81 the last of no less than 12 men – twelve!! – under 3:32.

Two more came in under 3:32.42 making it 1.98 seconds from first to 14th. The lone passenger to fall off the caboose was George Mills, and he still ran 3:35.76.

This truly was an amazing exhibition of super-fast middle-distance running in depth. Jakob Ingebrigtsen has run faster (several times) this season and no less than eight men (including Ollie Hoare) were under 3:30 in the Bislett Games 1500 in early June. The extras were those tacked on the end of the train, with the fastest-ever times for places 11 to 14 recorded.

This truly was an amazing exhibition of super-fast middle-distance running in depth. Jakob Ingebrigtsen has run faster (several times) this season and no less than eight men (including Ollie Hoare) were under 3:30 in the Bislett Games 1500 in early June. The extras were those tacked on the end of the train, with the fastest-ever times for places 11 to 14 recorded.

Nor was this the only race of remarkable depth at the meeting. In the women’s 5000 – won by Gudaf Tsegay in 14:12.29 – the first eight finishers ran personal bests as did places 10 to 12.

Nor was this the only race of remarkable depth at the meeting. In the women’s 5000 – won by Gudaf Tsegay in 14:12.29 – the first eight finishers ran personal bests as did places 10 to 12.

Sure, super-shoes. OK, pacing lights, too. But something’s going on here and (like Dylan’s Mr Jones) we don’t know what it is.

On pacing, the race tempo certainly was even. Two weeks ago when Ingebrigtsen ran 3:27.14 in Silesia, he went through 400 in 54.82, 800 in 1:50.72 (55.90) and then McSweyn took him to 1200 in 2:46.82 (56.10). Corresponding splits in Oslo were 55.47, 1:51.68 (56.21, and 2:46.81 (55.23).

In London, it was almost rock-steady even for the first two laps – 56.13 and 56.08 for 1:52.21 – followed by a slight drop-off to 2:49.83 (57.62) for the third lap. The fact that Ingebrigtsen won both Oslo and Silesia by some margin should not disguise the reality that there was close and fast racing chasing him home. London was effectively an Ingebrigtsen race without Ingebrigtsen winning by a second or so.

A less pronounced example of this ‘train’ effect was Faith Kipyegon’s first of three world records in the 1500 metres in Florence. Kipyegon was on a super-express of her own with her 3:49.11, but Laura Muir and Jess Hull were rewarded for at least trying to keep up with times of 3:57.09 and 3:57.29 in second and third places. The second-class carriage in that race ranged from Ciara Mageean’s 4:00.95 in fourth, through Abbey Caldwell’s sixth of 4:01.34 to Linden Hall’s 4:02.43 in tenth.

A less pronounced example of this ‘train’ effect was Faith Kipyegon’s first of three world records in the 1500 metres in Florence. Kipyegon was on a super-express of her own with her 3:49.11, but Laura Muir and Jess Hull were rewarded for at least trying to keep up with times of 3:57.09 and 3:57.29 in second and third places. The second-class carriage in that race ranged from Ciara Mageean’s 4:00.95 in fourth, through Abbey Caldwell’s sixth of 4:01.34 to Linden Hall’s 4:02.43 in tenth.

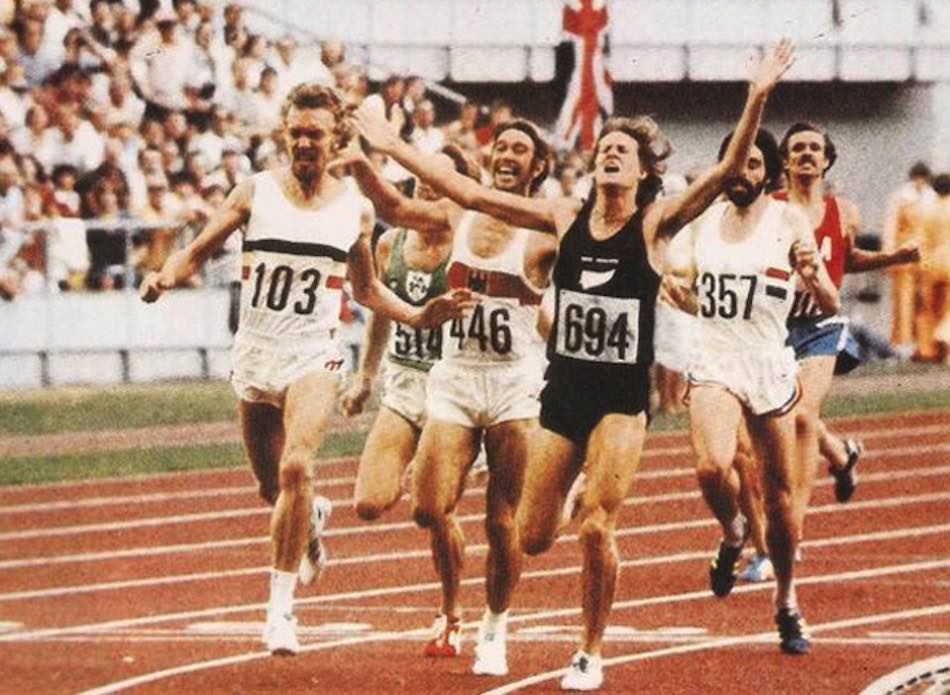

Sometimes – like the peloton in a bike road race – the ‘train’ forms behind a runaway leader. When Filbert Bayi dashed off in seemingly mad pursuit of a gold medal and world record in the Christchurch 1974 Commonwealth Games, the formation of a chasing pack was a matter of hanging together rather than separately.

In the end it was close-run, or at least gave an appearance of it. Bayi got his gold and his record in 3:32.2 as behind the train of John Walker (3:52.52), Ben Jipcho (3:33.16), Rod Dixon (3:33.89) and Graham Crouch (3:34.22) became the second, fourth, fifth and seventh fastest of all-time.

In the Munich 1972 Olympic women’s 1500 – the event’s Games’ debut – the brilliance of Lyudmila Bragina and the sense of history combined to produce a slew of fast runs. Bragina had set one world record two months before the Games, but now she went world record in heat, semi and final – 4:01.38 – dragging others to fast times, including Australia’s Jenny Orr, eighth in the final and national record 4:08.06 in the semi.

So pronounced was the effect of that Olympic 1500 that two years – and a further European championships – later 14 of the top 20 performers all-time still came from the Munich Games.

I may be wrong, but I’m under the impression that the “train” effect is stronger now than at any other time I can recall. Of course, all things come and go in their turn in sport, but right now it seems that all you have to do to run fast is turn up at the right station and the right time and get on the train.

And then, to borrow a line from Van Morrison, all you’ve got to do is “keep on moving, keep on moving on a fast train.”