A column by Len Johnson

Neil Robbins knew Ron Clarke well enough to call him ‘Fat’, Clarke’s boyhood family nickname. He was a teammate of John Landy and Marjorie Jackson; a clubmate of Les Perry, Geoff Warren and Dave Stephens, ‘the Flying Milko’. He trained with Merv Lincoln and many others under legendary coach Franz Stampfl.

Robbins, who passed away on 6 December at the age of 91, was also Australia’s pioneer in the steeplechase, finishing seventh in the country’s first home Olympics in Melbourne in 1956, the first occasion Australia had been represented in the event. A lifelong supporter of Footscray Football Club (now the Western Bulldogs), he would have appreciated performing well on the MCG where the Bulldogs had won their first Aussie Rules premiership just two years earlier.

Until Kerry O’Brien finished fourth in Mexico City 12 years later, Robbins’s was the best place attained by an Australian in the Olympic steeple. Forty years further on Youcef Abdi finished sixth in Beijing: Robbins, O’Brien and Abdi remain our only three male finalists.

At the time of the 1956 Olympics, Australia had never staged a national championship in the men’s steeple, and would not until the 1957-58 season (even then, only Melbourne and Sydney had a track with a water jump). Victoria and New South Wales had staged state championships. Most tracks were grass back then. One can easily imagine grounds-keepers would have been reluctant to dig up pristine ovals for a water jump.

At the Olympic selection trials in Melbourne Robbins, fellow-Victorian Ron Blackney, from Landy’s Geelong Guild club, and NSW’s Graham Thomas made the team.

Blackney and Thomas did not get through the heats. Robbins, having improved his technique as a result of Stampfl’s training, ran an Australian record to qualify for the final. Figuring that he could not rely on his kick, Robbins took the pace up mid-race, breaking the field up. In the final, won by Britain’s Chris Brasher of Bannister sub-4 minute mile fame and later co-founder of the London marathon, won in 8:41.4. Robbins was seventh in 8:50.0, improving the national record he had set in the heat by just over five seconds.

Robbins also had a formative influence on a young Ron Clarke during the early phase of his career. It was Robbins who influenced Clarke to seek guidance from Stampfl in 1955 and, while the coaching relationship didn’t last, it introduced a degree of organisation into Clarke’s training. Robbins had met Clarke a year or so earlier when he had offered him a lift to an athletics meeting at Kerang, then home to Australian sprint hurdles champion Ray Weinberg.

Clarke was the relief driver. As he describes it in The Unforgiving Minute, it was a harrowing experience. “When I first got behind the wheel,” Clarke wrote, “I forgot to throw the clutch, crunched the gears and had the car jerking along for 50 or 60 yards.”

Ian Ormsby, another athlete from the Kerang area, had mown out a track on the family property. Clarke told Ormsby he had never really trained. And Ormsby mentioned it to his friend, John Landy. A few days later Clarke received a “very scrappy note” (Landy’s apologetic description) with a detailed training schedule.

It’s no surprise, then, that Neil Robbins was one of the handful of spectators and friends on hand for Clarke’s attempt at the world six-mile record in the 1963 Zatopek 10,000. Nor that his role was to hold a watch and call out Clarke’s lap times. Clarke sprinted to the six-mile finish (some 340 metres short of 10,000) to beat the record set by Hungary’s Sandor Iharos. It might have ended there, as Clarke momentarily stopped to catch his breath, until he heard Robbins yell: “Keep going, ‘Fat’,” the nickname bestowed upon a chubby, five-year-old Clarke, “you’ll get the other one.”

Robbins would have a similar tale to tell any time you met him (which was often as he was a regular attendee at Melbourne’s Zatopek race, the annual Melbourne Track Classic and most other athletics functions). One story he didn’t relish was his disqualification in the six miles at the 1952-53 Australian championships in Perth. Suffering the effects of Perth’s heat, Robbins got the wobbles, eventually taking a couple of steps on the inside of the track. He was disqualified, an unjust decision which left Les Perry fuming.

“It’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard,” said Perry. “The fellow ran a good, game race and didn’t deserve that treatment.”

Like Clarke, Robbins had an exposure to numerous strands of influence. Williamstown club-mates Les Perry, Geoff Warren, Dave Stephens and half-miler Doug Henderson, among others, would have given him a keen appreciation of Percy Cerutty’s philosophy and he trained with Stampfl at Melbourne University.

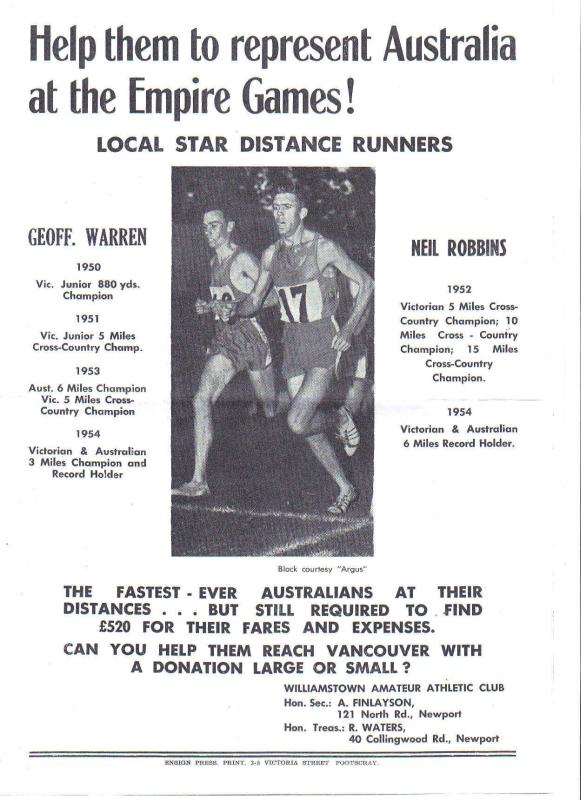

Robbins came to the steeple from the longer distances. He won the national cross-country title in Adelaide in 1952. He was selected for both the three and six miles in the Vancouver 1954 Commonwealth Games team, but things did not go well for him there.

Perhaps it was that experience which swayed Robbins in his choice of events for Melbourne. Whatever it was, the decision to run the steeple proved to be a wise one indeed.

Despite solid representation since, Australia has had only two other finalists in the men’s steeple – Kerry O’Brien (fourth in 1968) and Youcef Abdi (sixth in 2008). Otherwise Abdi (in London 2012), Chris Unthank (1996) and Peter Nowill (2004) have all run competitively without getting through. Shaun Creighton – ninth in 1993 – is the only world championships finalist.

The women’s event was not added until Beijing (Olympics) and Helsinki 2005 (world championships). In that time Madeline Hills (seventh) and Genevieve Gregson (ninth) were Olympic finalists in Rio, with Gregson also being a finalist at the past two world championships.

Amongst that group, at that level, Neil Robbins stands as tall as any other. Condolences to his family.