A column by Len Johnson

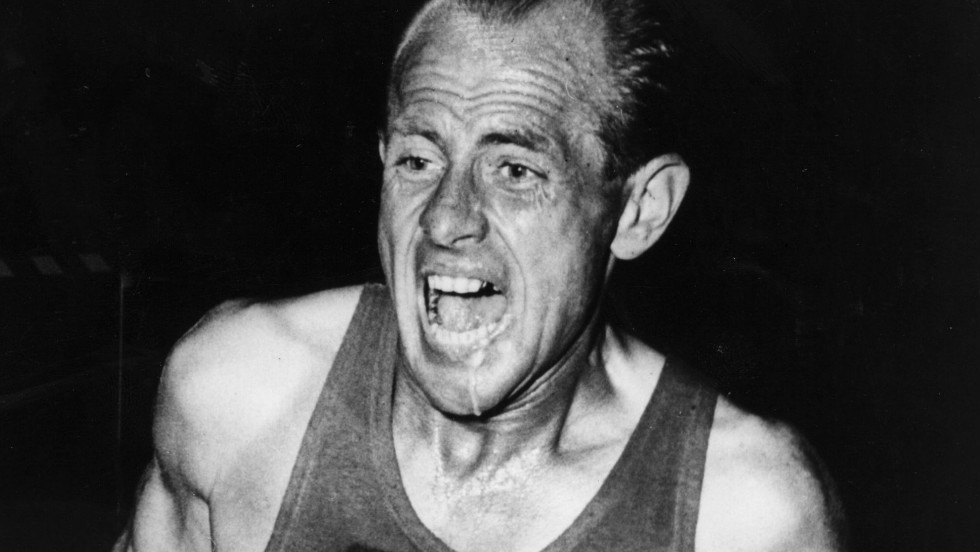

Few runners kept up with Emil Zatopek during his brilliant career. Even fewer got past the Czechoslovakian champion. And of those who did, hardly any stayed ahead of ‘Zato’ all the way to the line.

If it was hard enough catching up with Zatopek through his career, it is virtually impossible to do it now. Zatopek’s greatest Olympic feat, winning the 5000 metres, the 10,000 metres and the marathon at the Helsinki 1952 Olympic Games is almost impossible to emulate. It certainly can’t be done in the manner in which he achieved it, and almost certainly can’t be done at all.

Zatopek’s achievement was, and remains, unique in more ways than one. No-one else has done the distance treble, the closest being Lasse Viren who won the 10,000 and then the 5000 in Montreal in 1976 before finishing fifth in the marathon.

There was another unique element to the treble, however. Helsinki 1952 was Zatopek’s first marathon. Others have won the Olympic marathon in their debut at the event, but without attempting, much less winning the track double first.

Viren was actually trying exactly the same feat when he lined up for the marathon in Montreal’s Olympic stadium the day after his win in a torrid 5000 metres final. He had never run a marathon before.

Viren also faced greater physical demands than Zatopek. The 10,000 metres was a straight final in 1952. The 5000 had heats, but there were two clear days between the final on 24 July and the marathon on 27 July. In 1976 there were heats of the 10,000 and the 5000, and the final of the latter was the day before the marathon.

The 10,000 heats have since disappeared, this time probably forever. But there is an even tougher barrier standing between Zatopek’s feat and anyone brave enough to seek to emulate it – qualifying standards in the marathon.

To run the Olympic marathon, you now have to be qualified. At 2:17:00 (men) and 2:42:00 (women) that is not an insurmountable problem in itself, but fitting a marathon into a season which also allows you to qualify at 5000 and 10,000 is problematic to say the least.

The only possible way for a debutant marathoner to win the Olympic gold medal now is to be the sole representative of a country which is entitled to nominate one athlete because it has no other Olympic qualifiers. It goes without saying that such an athlete probably would not win the 5000 and 10,000, too, even if the rules allowed them to enter (which they do not).

And we can forget about any woman – no matter how good – even thinking about doing the Zatopek treble until the timetable is amended to parallel the men with both track races scheduled before the marathon.

The Zatopek treble appears destined to remain forever unmatched, even in the unlikely event that a runner as imaginative and ambitious as Zatopek returns to the scene.

It’s a pity, really, because Zatopek’s Olympic marathon was the stuff of legend. He was expected to win the 10,000 metres and did so easily, 15 seconds ahead of Alain Mimoun and just over 30 in front of the bronze medallist. The 5000, the one which defied him four years earlier in London, was tougher, but he won by just under a second from Mimoun with Herbert Schade third and then Gordon Pirie, Chris Chataway (who fell on the home turn) and Australia’s Les Perry.

Then, the marathon. Zatopek’s run was the stuff of legend. His tactics were basic, stick with Peters and follow the world record holder’s moves. Presumably this was on the premise that the fastest marathoner in the world must know something about marathon running.

This led to one of the most celebrated conversations in the history of marathon running, which occurred when Zatopek and Gustaff Jansson of Sweden ran up to Peters at around the 20km mark. The exact content will never be known, but the gist was that Zatopek asked whether the pace was too fast and Peters replied that it was “too bloody slow.”

Zatopek didn’t spend too long pondering the nuances. He took over the lead soon afterwards, eventually going away to win by over two-and-a-half minutes in an Olympic record.

(Apocryphal or not, this story had an echo in the 1976 marathon when Viren’s tactics were to follow Shorter. This worked for the first 10km whereupon Viren lost the defending champion as the large pack shuffled around at a drink station. As Viren cast anxious glances over either shoulder, Shorter called out: “Yoo-hoo Lasse. I’m over here.”)

Zatopek’s win in Helsinki was the middle leg of a hat-trick of Olympic victories by debutant marathoners. Delfo Cabrera of Argentina was running his first marathon in London in 1948, as was Mimoun when he memorably won in Melbourne in 1956.

It can’t happen now, which is a shame. Whether the world’s championship-winning track distance runners – and their agents – even want to step into the marathon is another matter, but it would be nice if the rules once again allowed them the option.

Comments are closed.