In writing last time about the Melbourne-Echuca marathon relay and the toughness of the distance runners of that era I wondered about the training they used to do.

I made the observation: “These men may not have done the high training mileages of today, but they certainly were tough when it came to racing.”

A little further digging into the material I had been sent concerning the 1953 marathon relay and the runners in it, I came across an article which gave some insight into this training.

Ross Shilston, son of one of the participants in the relay, Mark Shilston, sent several copies of The Australian Athlete, a track and field publication of the day. One of the contributors was Joe Galli, a legendary athletics writer for Melbourne’s weekend sports paper, The Sporting Globe.

The Globe was almost universally known by Victorians as ‘the pink paper’ or ‘the pink comic’, a reference not to its politics but to the colour of the paper on which it was printed. Part of the ritual of growing up in Melbourne was the wait at the paper-shop on Saturday nights for the truck to deliver ‘the pink paper’ with its final-siren reports of the day’s VFL (Australian Rules) football matches.

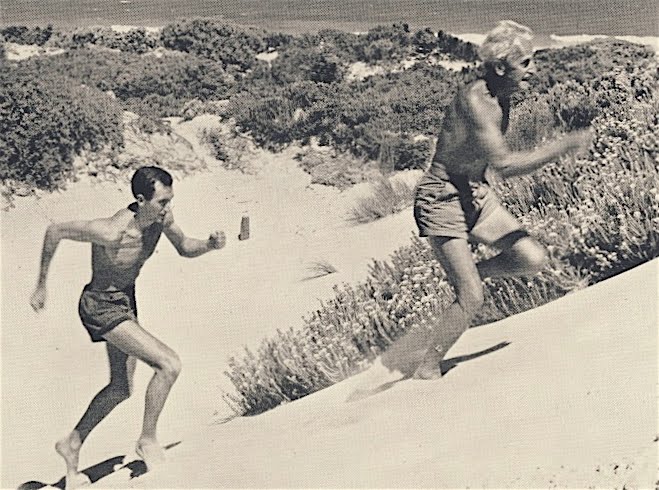

I digress. A more regular contributor to Australian Athlete was Percy Cerutty, who was at this stage (late 1948-early 1949) was running some of the races and coaching many of the athletes he wrote about.

Indeed, in 1946, at the time 50-plus years old Cerutty was impressing the likes of Les Perry and John Landy with his ability to do as he said, Cerutty finished fifth in the Victorian marathon championships behind four New South Welshman from the Botany Harriers club.

Just over two years later, in November 1948, Cerutty was writing about how Victorian distance runners, largely his Victorian distance runners , had turned the tables.

It was still a year before the first official Australian marathon championships, but by this time Victorians were travelling to Sydney for the NSW title and NSW athletes to Victoria for the Victorian state marathon.

Victorians had taken seven of the top 10 places in that year’s Victorian championship. Gordon Stanley of Victoria was the winner.

“There is no doubt in my mind,” Cerutty wrote, “that marathon racing must be built upon hundreds of miles run at easy paces. There is no room in our schedule for ‘speed’ work over six miles, or 10 miles under the hour. This work comes in our early races, the 15 and 20 milers. Even in the late stages of our marathon training we do not dissipate our built-up energy by overdoing the fast work.

“Given the right temperament, and the tenacity to run 200 miles per month (emphasis mine) for many months, we have learnt that any athlete can run the marathon inside three hours time. Yet only two years ago, 2:58:11 (by Cerutty) was the best time ever recorded by a Victorian amateur.”

Cerutty also observes that the Victorian group largely trained together and that bob Prentice, who did not, trained along similar lines.

The one man to break the Victorian stranglehold was Cecil “Chicks” Hensley, the winner of the 1946 marathon. Hensley finished second to Stanley, leading Cerutty to note: “At 40, he is running faster times than ever.”

A quick digression on Hensley, who coached Al Lawrence, the first Australian to win a medal in an Olympic long-distance event with his bronze in the 10,000 metres in Melbourne in 1956.

In his yet-to-be published book, Footprints On Olympus, Lawrence describes his meeting with Hensley.

In 1945, I was taken in hand by a man who was to profoundly influence me for the rest of my life. Cecil ‘Chicks’ Hensley was captain of the Botany Harriers and the mayor of Botany when I first met him. ‘Chicks’ had never won a distance running championship until he was 34 – an age when most distance runners had retired – and throughout his career had fought to elevate the standard of distance running in his club, state and country.

Lawrence argues that Hensley, more than the publicised coaches of the era, was the architect of future Australian distance running prominence and success. He argued lon, and successfully, for the introduction of distance races for juniors and was a fervent believer that Australians could succeed on the world stage.

He ridiculed the notion that the Australian climate was the culprit that prevented the country from producing world-class athletes, constantly preaching that it was a lack of method, not climate, that accounted for the conspicuous lack of Australian names in record books and Olympic results.

Sydney’s Hensley Field is named after Cecil Hensley.

The Australian Athlete was itself something of a revelation. As well as its broad coverage of the winter season – the editions were October and November 1948, and January, 1949 – it contained a write-up of the professional athletics.

Indeed, the cover photo of the January, 1949 edition depicted Australian professional sprint champion Frank Banner, while inside there was a further feature article on A.C. (Arthur) Martin winning the Colac (Vic.) Gift. Martin was the 1947 Stawell Gift winner.

All this, of course, was over 30 years before open athletics became a reality in Australia. It does indicate, however, that the divide between the ‘amateurs’ and ‘pros’ was not as wide as is sometimes depicted.

Finally, there was a note that Cerutty had imported copies of the book, Commonsense Athletics, by famed English runner Arthur Newton and these were on sale.

“Percy is well known as an enthusiast and is selling these books without any profit to himself,” the note says.

Percy Cerutty an “enthusiast” – now who would have guessed that. The cost was 6/6 (six shillings and sixpence), including postage, so he certainly wasn’t making enough to retire on.

The book covered such topics as “Stamina, and how to get it; Are breathing exercises injurious; Is massage good or bad; time-trials; and, Tactics and Food.”

It’s refreshing to learn that Runner’s World, Runner’s Tribe, run 4 Your Life and other current-day publications did not invent these issues!