A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

In 1985, aided by nothing other than his own ambition, Steve Jones ran away from a field of the world’s top marathoners to win the Chicago marathon in 2:07:13.

Jones was white, Welsh and 30 years old. He had never done long stints of training at high altitude. His personal bests at 5000 and 10,000 metres were very good, but not exceptional.

That day in Chicago, Jones’s ‘victims’ included Djibouti’s Djama Robleh, second in 2:08:08, and recent world record holder Rob de Castella, third in 2:08:48. Ignoring the designated pacemaker, Jones had powered through 10km in 29:30 – with only one runner clinging on, and the half-marathon in 61:43, by which stage he was magnificently alone.

Jones reportedly ran only 80-or-so miles per week, most of it at a pretty solid pace.

De Castella, beaten by Jones for the second consecutive year in Chicago, came back to his home base in Canberra obsessed with the need to up his overall training tempo. For the next few months, he made running ‘hell’ for his training mates around Stromlo Forest. I know; I was one of those eating his dust, though far better runners than me were also left straggling.

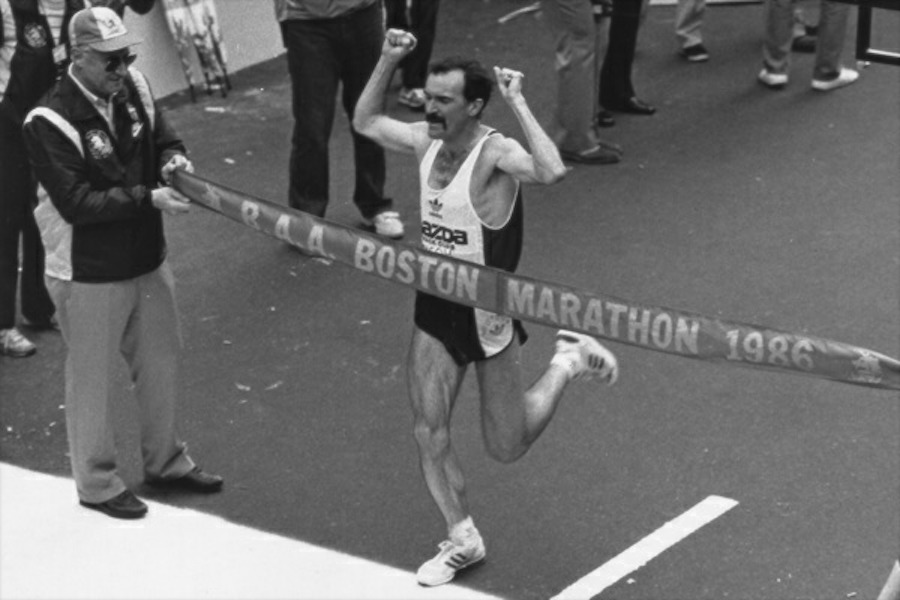

A few months later, having moderated his zeal a little and equalled his lifetime best for a track 5000, de Castella ran 2:07:51 to win the 1986 Boston race. Not as fast as Jones, maybe, but possibly its equivalent given Boston is hardly a fast course except in the one year in 10-15 when the wind blows the right way.

‘Deek’ ran 100-plus miles per week and had done limited training at altitude.

Given the examples of Jones and de Castella, can someone then tell me on what planet it is not possible for a 26-year-old Norwegian, with virtually unbroken training at high altitude for the entire year, to run 2:05:48.

Sondre Nordstad Moen did just that in winning in Fukuoka on Sunday, 3 December. It was 50 years to the day since Derek Clayton ran a world best 2:09:37 there in 1967. Then he ran even faster – 2:08:34 – in Antwerp 18 months later. It was almost a decade – and many unavailing attempts to better them – before Clayton’s times were questioned. Antwerp, a one-off course, must have been short, the sceptics proclaimed, and Fukuoka, conducted by those frustratingly efficient Japanese officials, must have been short that year.

Like runners, innuendo moves faster these days. Moen’s run has been greeted with scepticism in some quarters, based on his seeming improvement all of a sudden. Before Fukuoka, his fastest was 2:10:07, run in Hannover earlier this year. His half-marathon best was 62:19 at the start of 2017; he improved to 59:48 in Valencia in late October.

Something must be going on, was the conclusion to which many immediately jumped.

But wait, Moen is coached by Renato Canova, renowned coach and/or mentor to many of the world’s top distance runners. Canova, who is refreshingly willing to debate on social media, responded to some critics on the LetsRun message boards.

Moen, Canova said, had committed to full-time training this year and had spent over 230 days at altitude, “the most part alone, having focus in training, eating and resting only.”

Moen’s results, according to Canova, could be explained by a single-minded approach to hard, clean training. He did not add, but could have, that this approach may not be sustainable.

Of course, it is all too painfully true that Moen could be doping. Anyone could be, with or without the knowledge of coaches, training partners, life partners and, as we have seen all too often, despite regular, apparently sincere, assertions that they are clean. It is also true that an athlete’s regularly passing tests is no guarantee he or she is competing clean.

As painful as are all those realities, I find it even more painful that so much scepticism surrounds a significant improvement in performance. As most of us know from our own experience, neither improvement, nor decline comes in linear progression. When you are on the up side of the performance curve, progress is regularly marked by big jumps; ditto for big drops on the down side.

Then there is the “it’s not possible to run this fast/jump this high, or far/throw this far, without doping” line of argument. What are record-breakers if not outliers, and since when do outliers follow the same rules as the average performer. That is why they are outliers.

It is undoubtedly true that athletics – any sport – suffers self-inflicted harm when athletes test positive for performance-enhancing drugs. It is equally true that it suffers just as much self-inflicted pain when we too quickly assume significant performance advance can only by explained by their use.

End

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Len Johnson has been the Melbourne Age athletics writer for over 20 years, covering six Olympics, eleven world championships and six Commonwealth Games. He is also a former national-class distance runner. For over a decade Len has bee Runner’s Tribe’s lead columnist. Len also writes for IAAF. He has recently been named an Athletics Australia Lifetime Member. He is also the author of ‘The Landy Era’.