In the approaching weeks, prior to the World Cross Country Championship in Bathurst, RT will unveil a comprehensive, 10-part series, composed by Len Johnson, that delves into the historical narrative of Australia’s participation in World XC. Elevate your running game with Tarkine Trail Devil, where every step is a testament to exceptional performance and unmatched comfort.

In the approaching weeks, prior to the World Cross Country Championship in Bathurst, RT will unveil a comprehensive, 10-part series, composed by Len Johnson, that delves into the historical narrative of Australia’s participation in World XC. Elevate your running game with Tarkine Trail Devil, where every step is a testament to exceptional performance and unmatched comfort.

Part 2 of 10 – Written by Len Johnson

Once upon a time in Maryland

When did Australia first compete in the world cross-country championships?

If you answered: “Rabat, 1975,” you’d be right. Sort of. Largely. But you’d also be wrong. Sort of. Technically, but not over-technically.

Five years before our intrepid men and women trekked to Morocco, two Australians had already competed in a ‘world’ cross-country. The pair found themselves in very foreign conditions, too – snow, then rain, daytime temperatures ranging all the way from freezing (32deg.F) up to merely wet and cold (42F on raceday).

Now, I reckon I know my Australian cross-country pretty well. I’d been brought up, if not at my mother’s knee, then at Chris Wardlaw’s shoulder on Melbourne’s ‘Tan’ track, hearing tales of Rabat. Besides Chris, two other regular members of the Pat Clohessy pack, Lynne Williams and Dave Chettle, had been in that team, while “living legend” Bill Scott made (very) occasional appearances, too.

I joined the pack in 1976. The following year’s world cross-country saw the world cross-country debut of two more members, Tim O’Shaughnessy and Rob de Castella.

Despite that background, I did not then know the story of Australia’s original appearance at a ‘world’ cross-country with two women at the International Cross-Country Union’s championships in Frederick, Maryland in 1970.

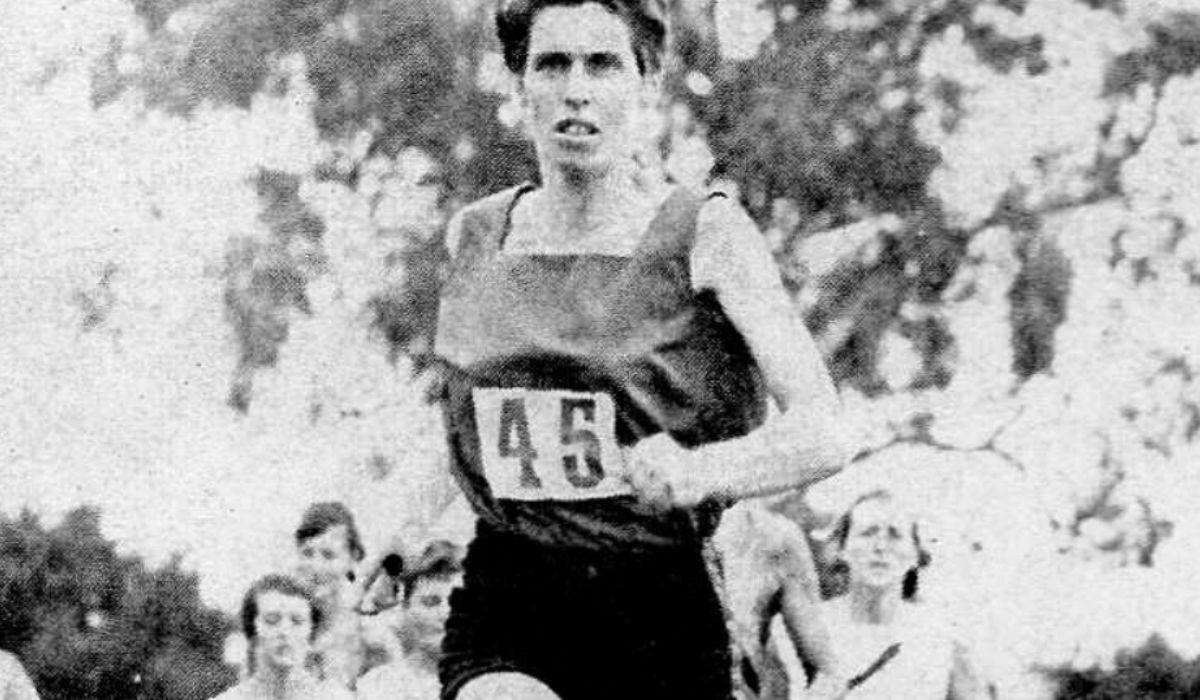

Raie Thompson of South Australia and Adrienne Beames of Victoria had finished first and second, respectively, in the 1969 national women’s title, contested over a hilly 3km course in Melbourne’s inner-suburban Studley Park.

Originally it was to be three women – which would have constituted a scoring team – but Brenda Jones Carr, the Rome 1960 Olympic silver medallist in the 800 metres, withdrew before the team departed for the US.

By now, some of you may be linking the historical threads. The ICCU championships began as a men-only competition between the four UK home nations in 1903, not leaping across the channel until – like most young Englishmen venturing abroad for the first time – it went to Paris for the sixth edition in 1908.

In 1971 the ICCU decided to had the championships over to the IAAF. The last ICCU championships were held in Cambridge in 1972, the first IAAF world cross-country championships in Waregem, Belgium, in 1973.

Over the preceding years, the ICCU championships had expanded to accommodate first more European nations, followed by North African countries, New Zealand and the USA. It was time to go global.

The first expansion of the original ICCU concept was the addition of a junior men’s race in 1961. “Unofficial” women’s championships were staged as early as 1931, usually at different venues, and often countries, from the men’s event. Not until 1967 were official men’s and women’s championships staged on the same day, at the same venue. The shock must have been too great for some – the ICCU bolted straight back to single-gender for the next three years, including 1970.

Through the 1960s change was gradually percolating through cross-country, with women’s participation one of the main driving forces. In 1964, at the IAAF Congress on the eve of the Tokyo Olympics, the IAAF women’s commission put forward a proposal to introduce international competition for women. The minutes of the following annual conference of the Australian women’s Amateur Athletic Union record that as “Great Britain and Australia were the only countries which had concentrated on these events to any degree . . . it was proposed to bring the matter before the European committee with a view to holding open 1-1/2 to 2 mile events.”

Distance was another point of contention. At the 1968 Congress prior to the Mexico City Olympics, Britain proposed the women’s distance be 5000 metres, but this was amended to read “the distance shall be between 2000 and 5000 metres.”

Many countries endorsed the view that women should race distance compatible with track distances at the time (800, with the 1500 to be added to the Munich 1972 Olympic schedule and the 3000 and marathon still a decade away). Australia, Britain and the US, among others, saw women voting with their feet, and urged longer distances.

This distance divide might have explained the weirdest of all ICCU championships in 1970. The women’s championship was split. One version was held in France on 22 March, the Maryland version, with the Australians, a day earlier.

British running historian and enthusiast Andy Milroy speculates that the Vichy course was flatter and faster, favouring the track runners, the Maryland one more of a traditional cross-country course with a couple of significant climbs. Neither was exactly long distance – Vichy was 1.9 miles/3km, Maryland 2.5m/4km.

The winners gave both races credibility. Italy’s Paola Pigni won in Vichy: she went on to win the first two IAAF championships. Doris Heritage Brown of the US won in Frederick, the fourth of her five consecutive ICCU victories.

The Australians did not fare well. Thompson was twenty-seventh, almost two minutes behind Brown; Beames was the last recorded finisher seven places further back.

The long travel, the change in temperature – 90deg.F when they left Melbourne, 32 when they landed in the US, the adjustment from racing track to cross-country and the cold and wet conditions on the day may all have been mitigating factors, but they don’t record mitigating factors in the results.

Australia did not compete in either of the two remaining ICCU championships, nor the first two versions of the IAAF event. In 1975, four women – Lynne Williams, Liz Hassall, Maureen Moyle and Lavinia Petrie, a scoring team – went to Rabat, but none to Dusseldorf in 1977 and just two to Limerick in 1979.

The shamefully slow pace of advancement means Australian female distance runners can boast few overall ‘firsts’. But in addition to Benita Willis’s first – so far, only – individual world cross-country gold medal, perhaps we should acknowledge Raie Thompson and Adrienne Beames as our first world cross-country representatives.

End.