By Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

I read an interesting blog this week which suggested the narrative around women’s sports was in need of urgent change.

Sally Bergesen, founder of the Seattle, USA-based apparel company Oiselle, wrote: “when you look at the dominant narratives for female athletes, it becomes clear that many are not focused on a woman’s heroic talent or strength but centre more around the simple concept of inclusion.” It is a well-argued piece which you can read in full here.

One action arising from the discussion Bergesen had with her running group was to “put a stake in the ground for the women’s mile.” They would add their voices to those talking about making sub-4:30 for women being a benchmark similar to sub-four minutes for men.

Personally, I’ve never been that sold on the idea of ‘barriers’. Four minutes became a barrier for all sorts of historic reasons – one of them a wider recognition of Imperial measurements which, even in this world of Brexit and Trump ain’t coming back any time soon; another, the pause in progress in all sports imposed by World War II – which are not applicable these days.

And it was a ‘barrier’ because it was blocking the path forward. Four minutes was ahead of historic and contemporary performances until 6 May, 1954, not the moderately good performance it is now.

Narrative, now that’s another matter. Bergesen cites the stories of Emma Coburn and Joan Benoit, but one that came to my mind this week, month and year is Paula Radcliffe.

The third day of the recent world championships in London – 6 August, very appropriately marathon day – was also the fifteenth anniversary of one of Radcliffe’s most memorable races. On that day, in Munich’s Olympic stadium (still more appropriate serendipity), Radcliffe splashed her way to a 30:01.09 European record in the 10,000 metres, leaving Sonia O’Sullivan over 45 seconds in her wake.

Run in pouring rain, it was the second-fastest 10,000 metres by a woman to that point. In a forlorn attempt at empathy, I had watched the race on a TV in the bar at Crystal Palace, rain still dripping from my own running gear as I had gone to the track without any dry clothes, much less anything waterproof.

The 10,000 run was just one of a series of performances in a tour de force year in which Radcliffe excelled in cross-country, on the track and on the road.

Statisticians are not normally given to flights of hyperbole, but writing in Athletics 2003, the Association of Track & Field Statisticians’ annual publication, stats doyen Peter Matthews variously described Radcliffe’s performances as “a sensational debut”, “extraordinary”, “she could well have got the world record”, “astonishing” and “capping an incredible year”.

It began in Dublin in March where Radcliife simply “retained her title” but as said title was the world cross-country championships, that was as much as most achieve in a year.

The “sensational debut” came three weeks later in the London Marathon when Radcliffe followed a 71:02 first half with a 67:54 second to complete her first marathon in 2:18:56, a world best for a women-only race.

The “extraordinary performance” came on 19 July in Monaco when Radcliffe chased Olympic 5000 metres champion Gabriela Szabo home over 3000 metres in 8:22.20. Adding to the amazement, this was her first track race of the season, first race of any kind, in fact, since the marathon.

Nine days later in Manchester, Radcliffe won the Commonwealth Games 5000 metres in 14:31.42. The world record at the time stood at 14:28.09 to China’s Bo Jiang. Seeing Radcliffe ran the first kilometre in a sedate 2:59.91, “she could well have got the world record” indeed, and done it on her ear.

Another nine days and it was the “astonishing” 10,000 metres which won Radcliffe the gold medal at the European championships. You had to see the rain to appreciate the conditions, the athletes splashing through puddles of water and even water-resistant kit heavy with accumulated rainwater.

But Radcliffe was not done yet. Just over two months later, on 13 October in Chicago, she lined up for her second marathon. In London, even as a debutant, she had clearly been the class athlete in the women’s field. In Windy City, Radcliffe faced Catherine Ndereba, who had set a world best of 2:18:47 in Chicago the previous year, Constantina Dita, Derartu Tula and Deena Kastor.

No matter; Radcliffe “capped an incredible year” with another win, this time running 2:17:18. Again, she was faster in the second half than the first, reaching half-way in 69:05 and closing in 68:13. The added significance was that her time became the first world best to be officially recognised by the IAAF.

The very next year, Radcliffe also garnered the first official world record when she ran 2:15:25 in London. Two years later again, she ran what is still the fastest championship-winning time when she beat Ndereba, Dita and Tulu in the world championships in Helsinki in 2:20:57.

Radcliffe was U20 champion at the world cross-country in 1992 but it was a long time before she won anything of global significance as a senior (the world half-marathon in 2000 followed by her first cross-country title in 2001).

But once Radcliffe made the switch to the marathon she became a dominant force. There were hiccups – the major one a ‘dnf’ in the Athens 2004 Olympic race – there always are with the marathon, but she compiled a record that remains unsurpassed. Standing out amidst it all is that wonderful year of 2002.

A compelling narrative, I reckon.

End

About the Author-

He has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

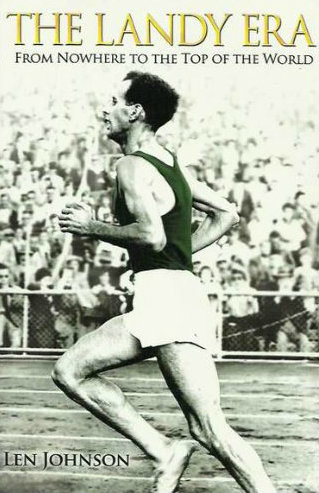

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.