Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

Many thoughts flashed through my mind after Eliud Kipchoge’s world record marathon.

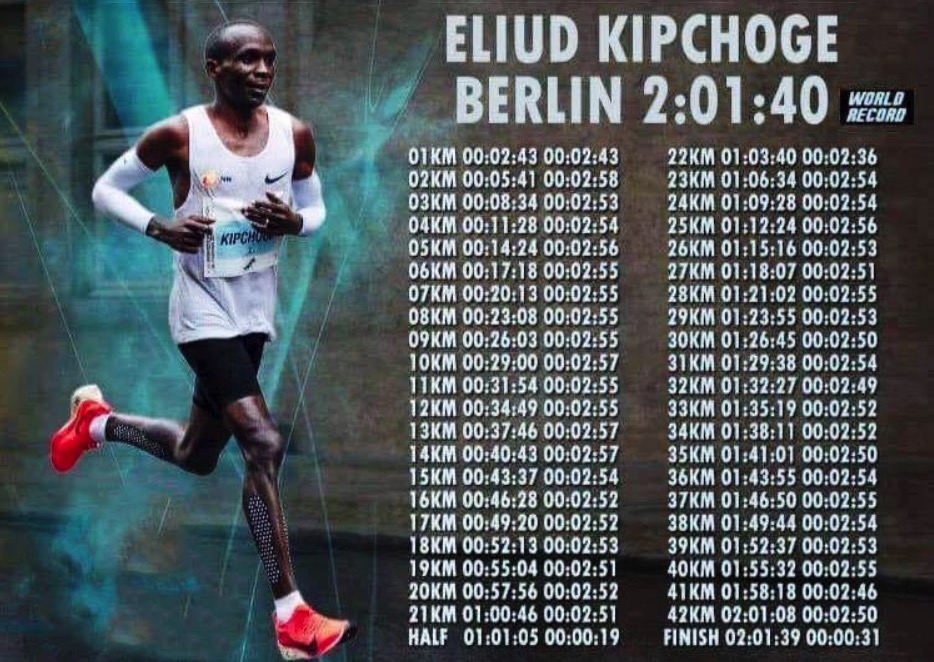

The first was: “Amazing.” Neither insightful, nor unique, but what else comes immediately to mind after a man runs 2:01:39 for the classic 42.195-kilometer distance.

Just about the second thought, possibly because it leapt out of the Berlin previews, was that Kipchoge had said he was going into the Berlin race aiming for a PB, not necessarily the world record.

“I am not thinking about the world record,” Kipchoge said. “My eyes are on a personal best.”

On the surface, it seemed a pointless distinction given that the attainment of one would almost certainly mean the attainment of the other. Going into Berlin, Kipchoge’s fastest official marathon was a 2:03:05 in London in 2016. An improvement of just 0.2 seconds per kilometre would see him under Dennis Kimetto’s 2:20:57.

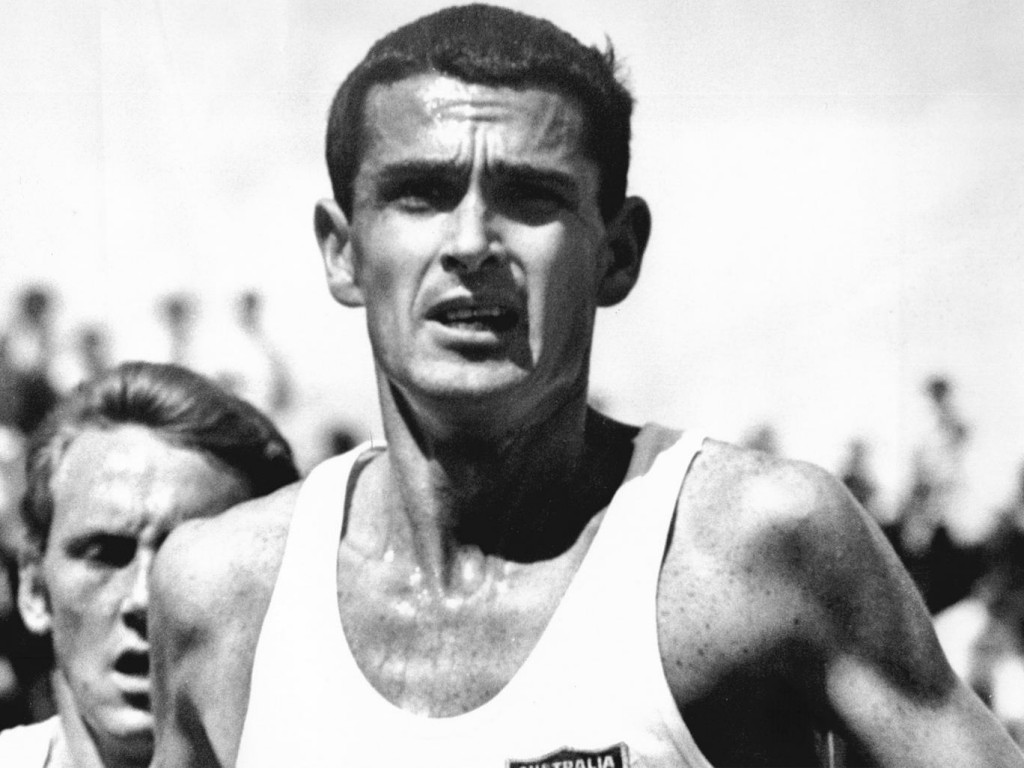

Some people highlighted this apparent disconnect. I thought of Ron Clarke and something he once said about world records. Clarke set 18 world marks as he re-defined track distance running from 1963 to 1967, so had some familiarity with the topic.

In line with the curse of the writing class, I can’t find the exact quote, so a paraphrase will have to do. Asked how he went about continually breaking world records, Clarke replied that it was not that hard.

Once he had broken one, Clarke said, breaking further world records was just running a PB.

Although Eliud Kipchoge had not set a marathon world record before Sunday, 16 September in Berlin, I detected more than a hint of that sort of thinking in his pre-race comment. The doing of it aside, no-one could be better placed to break the world record.

Kipchoge had run 2:00:25 in the artificially-paced Breaking2 project. Several times, too, circumstances and/or conditions had conspired against him. Berlin 2015 (2:04:00) was derailed by those flippin’, flappin’ insoles; the 2:03:05 win in London 2016 was tempered by having to race the world’s best track distance runner, Kenenisa Bekele, and then Stanly Biwott over the closing stages; and the 2:03:32 last year in Berlin saw him having to come from behind to see off the unexpected challenge of thereto-unknown Guye Adola.

Most recently, unseasonal heat, an ambitious opening half of 61 minutes, and a late-race battle with another Ethiopian, Shure Kitata, held Kipchoge to 2:04:42 in this year’s London.

All this created an impression that the world record would be toast as soon as Kipchoge got the right race and the right conditions. In Berlin last weekend, it was not so much toasted as charred to a crisp. Kipchoge slashed a massive 1:18 off Kimetto’s record, the biggest improvement in the men’s record since Derek Clayton’s 2:09:37 at Fukuoka in 1967 took 2:23 off Abebe Bikila’s previous mark.*

Kipchoge’s run, moreover, was solo over the last 17km, and accompanied by just one pacer from 15-25km. He only ever had three pacers, the first two dropping out at the 15km mark, a stark contrast to the phalanx of pacers usually associated with record attempts in Berlin.

His response to the diminishing assistance of the pacers was instructive. The departure of the first two at 15k was followed by a 14:18 surge to 20km, the fastest 5km split of the race. The last kilometre up to 25km took 2:56, whereupon the final pacer dropped out. Despite running solo from there to the finish, Kipchoge never ran a slower kilometre and rattled home over the final 2.195km in 6:07. Amazing indeed.

Another thought that occurred to me is how Kipchoge appears to have used his Breaking2 performance to leverage his own progress towards a two-hour marathon. It may remain unthinkable that anyone else can get there soon, but Kipchoge has put it just within the range of his possibilities.

When Kipchoge ran his 2:00:25 at Monza in May, 2016, he was aided by a team of pacemakers running in shifts. Moreover, they all ran the entire distance behind the windbreak of a large vehicle with a timing clock on top.

A view widely held both by those who thought intuitively and sports scientists was that such pacing might have been worth anywhere from one to two minutes (let’s leave aside the 4% shoes for the moment – please!).

Two ways of looking at Kipchoge’s Berlin performance then. First, give him similar pacing assistance to Monza and it might have been 1:59-something. Second, he has taken the confidence from the Monza experience into an actual race and split the difference between his previous best and two hours. And he did so running solo over the final 17 kilometres and virtually solo from 15km. At no stage did he have similar assistance to what he had in Breaking2.

As for the hype around the shoes and the drink Kipchoge used in Berlin and what either or both may have been worth – well, all you can really say is we must await further developments. For now, let the amazement continue undiminished.

* The greatest improvement in the marathon record since 2000 was Paula Radcliffe’s 2:15:25 in London in 2003 which took 1:58 off her previous world record.