That sinking feeling – Len Johnson Reporting from London – Runner’s Tribe

Pink Floyd famously imagined an elephant flying over Battersea Power Station.

I fancied I saw a kitchen sink on the first night of the world championships, flying over Queen Elizabeth Park. They threw everything but the kitchen sink at Mo Farah in the 10,000 metres; then they did throw the kitchen sink at him. Unless you’ve been away for the past six years, you’ll know that it didn’t faze him in the least.

Mo won. Britain celebrated. His third consecutive win in a world championships 10,000, one behind Kenenisa Bekele and Haile Gebrselassie. They both have four, but Mo’s have come as part as doubles, and there is every likelihood this one will, too. Bekele won a world champs 5000/10,000 double in Berlin in 2009; Gebrselassie never did. If Mo backs up in the 5000 in a few days’ time he will win his fourth such double in a row, his fifth straight 5000 title. Add in Olympic doubles in London and Rio and that makes five global doubles in a row. Unprecedented dominance.

Farah did not get Bekele’s 2003 championship record, but he did lead seven men under 27 minutes, the best in a championship race. I await someone else to do the authoritative stats, but I believe the most ever was nine at the 2011 Prefontaine Classic, a race won by – who else – Mo Farah.

It is said – and I am sure it will be said again this time – that Farah’s opponents have been intimidated, that they don’t try anything to beat him until it is too late and they are overwhelmed by his finishing speed.

It is also said (including by me at times), that Farah does not seem to be at all interested in what times he can run, but only in winning. But if it is unique in a runner of his achievements not to have also held the world record at 5000 or 10,000, it is likewise unique to have won 10 global distance championships in succession and to be in line for no.11. Alright, they come round faster these days than they did in the time of Nurmi, Zatopek, Kuts and Viren, but that is still a might impressive number.

As for the charge that Mo’s foes hand the race to him, well I reckon that’s nonsense. Like all great champions, his reputation does carry an element of intimidation: but winning all the time does that for any athlete, or team, for that matter. It also ignores the inconvenient fact that the one time Farah was beaten before he started this golden stream, he was out-sprinted by Ibrahim Jeilan. Anyone can be beaten in a sprint; a big part of Farah’s greatness is that he has not let it happen since the 2011 10,000.

He just does not let the late-race phase unfold in a predictable manner. It is amazing how often the man who does not win until the final lap, the final straight even, appears at the head of the race four or five laps out. In the game of cat-and-mouse, Mo Farah is one ferocious cat.

On his championship return to London’s Olympic Stadium, Farah faced any number of rivals determined to do him down. From the gun, Joshua Cheptegei, Godfrey Kamworor and Moses Kurong set off at a fierce pace. The first lap flashed by in 61 seconds: the breakneck speed dropped off a bit, but the fist 1000 was still 2:39 – just under 26:40 pace.

In response, Farah was initially further forward than usual, running mid-pack instead of at the tail-end. Soon enough, Kamworor’s teammates Paul Tanui and Bedan Karoki had joined in at the front, as had emerging young Ethiopian Abadi Hadis and his teammate jemal Yimer.

They attacked by turns. With six laps to go, Cheptegei was in the lead from the Kenyan trio, Hadis and Farah. Two laps later, Hadis was pushing the pace, the rare sight of an Ethiopian runner pausing the pace before the final sprint.

But with two to go, Farah was suddenly at the leader’s shoulder. Though there were still minor variations, he led or was no more than a step back from the lead until the finish.

Even so, four men could have won coming off the final bend. Farah grimaced and kicked hard. Suddenly, unless he folded like he did back in Daegu six years ago, four was reduced to one.

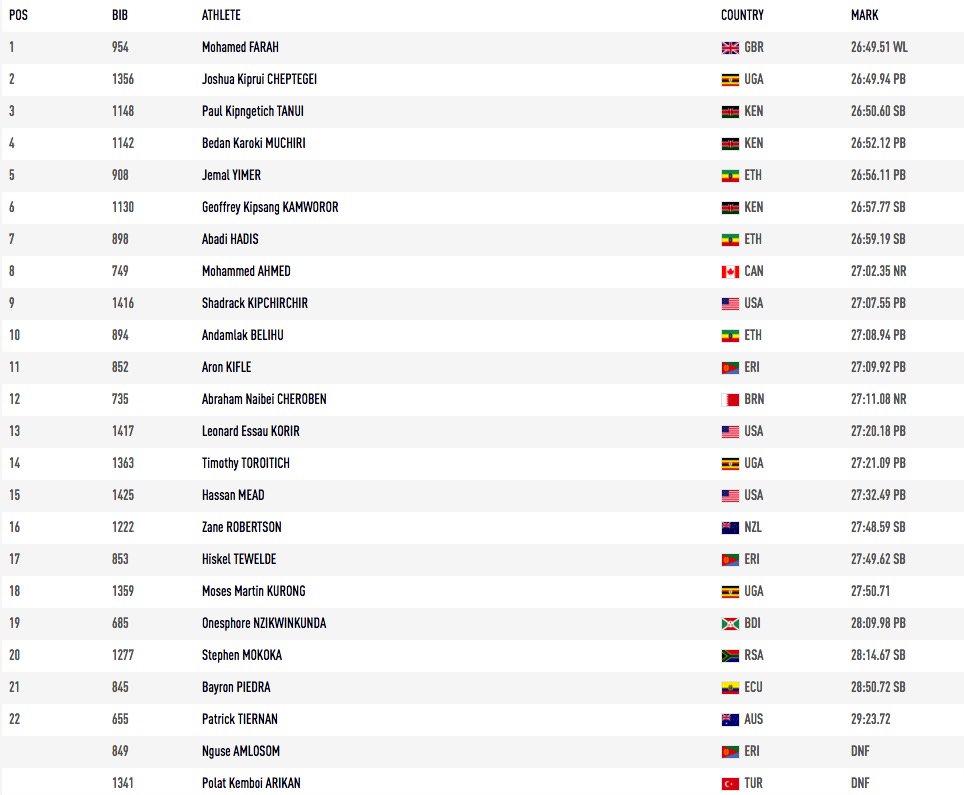

Farah won in 26:49.51, just short of Bekele’s championship record of 26:46.31. Cheptegei, who lost the world cross-country at home to Kamworor when he blew up late in the race, gained ground this time to hold off Tanui for the silver, 26:49.94 to 26:50.60. And Karoki, Jemal Yimer, Kamworor and Hadis also came in under 27 minutes.

Pigs might not fly. But Mo Farah had once again swotted the kitchen sink away as if it were a housefly. At least, after these championships, his rivals can stop thinking about ways to beat him.

End

Final results via the IAAF (visit their site here)