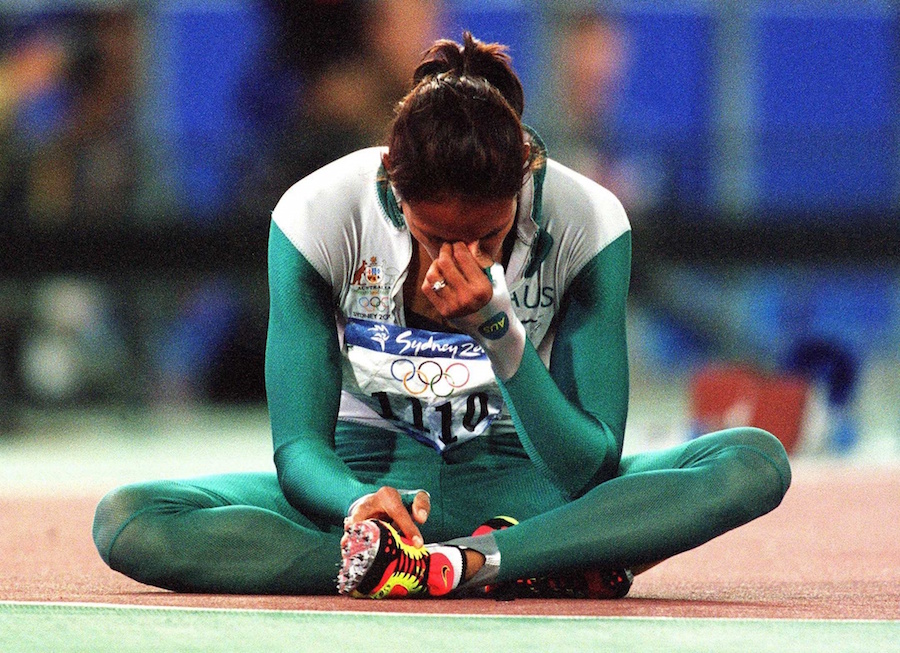

Barely a minute after the start of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games women’s 400 metres, Cathy Freeman was sitting in a crumpled heap on the track.

This was scarcely the pose you would expect of a gold medallist, but it was all Freeman had left after defying one of the heaviest loads of expectation experienced by any athlete in history.

Consider this list of horrors. The face of the Games: check. Carrying the banner for indigenous Australians: check. Carrying the banner for all Australians: ditto. Lighter of the Olympic Flame: check. Drenched in the process by errant fountain spray: check and double-check. Sick in her final build-up: check.

Oh, and not to forget, an overwhelming favourite for her event and seen almost universally as “Australia’s only chance of a track and field gold medal.”

No other incident more starkly defined this pressure than the response Michael Knight, NSW Minister for the Olympics, gave when he said the athletics schedule would not be changed to a nine-day program, meaning those who had bought a ticket for the women’s 400 final night would, in fact, get to see the women’s 400 final.

The minister’s take on this was that he had protected the Australian public’s right to come along on 25 September to see Cathy win her gold medal. No need for anyone else to pile on the pressure then!

Freeman defied it all to win decisively in front of an Olympic record 112,000 fans. Millions more watched on television in venues from outback community halls, to pubs and large screens erected in Sydney’s Darling Harbour, Melbourne’s Federation Square and pretty well every other major public space round the country.

Australia may not have 1.3 billion people, but on a per capita basis there just might have been more interest in Cathy Freeman’s Olympic 400 metres final than in any race of Liu Xiang’s career.

Can it really be 15 years ago to the day (Friday). At times it seems like yesterday, at other times another lifetime.

The medal came on top of a tumultuous year for Freeman. Her drawn-out personal and business split from Nic Bideau came to a head as they attempted to resolve their management issues. Freeman ran well in the domestic season but things seemed to be in chaos when she got to Europe – a perception further fuelled by media stories.

To be sure there was smoke – a training partner virtually turned round and left the moment he arrived at Freeman’s training camp in Bath. The trip to her first race in Italy turned into a drawn-out drama involving traffic jams, a delayed flight, landing in the middle of a thunderstorm and a belated dash to the track. Lost in all this was the fact that she won the race.

There were so many predictions of imminent disaster that is was something of a relief to arrive in London to find there was no fire. Freeman was in good spirits and focused very much on the job in hand even if the message filtering back to Australia was of a campaign in tatters.

Over the next few days I fielded lengthy phone calls from Fairfax colleagues in Australia, from my sports editor, and from Nic – all pushing the line that things were falling apart. I spent 30 minutes on the phone to the office from the car park of the team hotel near Heathrow.

Another half-hour went by in conversation with a senior Fairfax journalist while I waited for a train at Clapham Common station. It is London’s busiest station, connecting major east-west and north-south lines. I could tell this was so from the number of connecting trains I let go by as the conversation went on, and on.

The European ‘crisis’ averted, Freeman continued to train well and race undefeated until coming home. She had opted to stay in Melbourne until the last possible moment, a well thought-out plan threatened with derailment when she caught a cold in Melbourne’s spring ‘warmth’ and lost her voice.

Freeman survived that, the Opening Ceremony and drenching and everything her opposition could throw at her (though the only thing defending champion Marie-Jose Perec threw in was the towel, fleeing Sydney within 48 hours of her arrival claiming to have been stalked by an intruder in her hotel of whom, mysteriously, there was no corroborating trace).

I loved her line several years later to Ray Martin about the hiccups in the ceremony. Surely they must have annoyed her, he asked.

No, said Freeman. “I told myself: I’ve come here to win a gold medal in the 400 metres, not to light the Olympic cauldron.”

And win it she did, even if her first reaction was, understandably, to sit down on the track in a heap. She had coped with the pressure without missing a beat. It was its release which left her, for a few moments, unable to stand.

The women’s 400 was almost the mid-point of an unforgettable night with nine finals, the sort of session that no longer exists on the championship schedule because the rest day has disappeared.

Michael Johnson won a men’s 400 that went by almost unnoticed in the aftermath of Freeman’s win (I still can’t believe that happened, but it did). Maria Mutola won an Olympic 800 gold at her fourth try after an epic battle with Stephanie Graf and Kelly Holmes.

Paul Tergat stunned Haile Gebrselassie tactically by sitting until the last 200 metres of the 10,000 before unleashing his own finishing kick. Ultimately, Gebrselassie prevailed by inches in a race he regards as his finest ever. The winning margin was less than in the men’s 100 metres.

Gabriela Szabo just got the edge over Sonia O’Suillivan in the women’s 5000 metres.

Stacy Dragila set a world record in winning the women’s pole vault from Tatiana Grigorieva, Virgilijus Alekna threw the discus almost 70 metres to win gold and Anier Garcia beat Terrence Trammell, Allen Johnson and Colin Jackson in the men’s 110 metres hurdles final.

To finish the night, the three semi-finals of the men’s 800 metres were won by eventual gold medallist Nils Schumann (1:44.22), Djabir Said-Guerni (1:44.19) and Wilson Kipketer (1:44.22). The slowest man into the final was Hezekiel Sepeng, at 1:44.85.

The Baci chocolates on the pillow at the end of a perfect night, I called them back then.

It was all chocolates, actually, not a boiled lolly to be seen.