By Len Johnson

Someone recently had the temerity to suggest that this column lives too often in the past.

We could respond that there’s a lot more history in the past than there is in the present. And who knows the future anyway? But fair comment we replied and since then have tried to avoid the past as much as possible.

But what if someone else opens the window of history and invites you to come on in? Like Guardian Australia has done with its poll to discover Australia’s greatest sporting moment. The online newspaper invited readers to nominate their favourites before distilling the list down to a top 50.

Six athletics ‘moments’ made the long list – five at the Olympic Games, one at an Australian championship. Three directly involve competition, one of the other two happened in-competition, the fifth occurred post-competition.

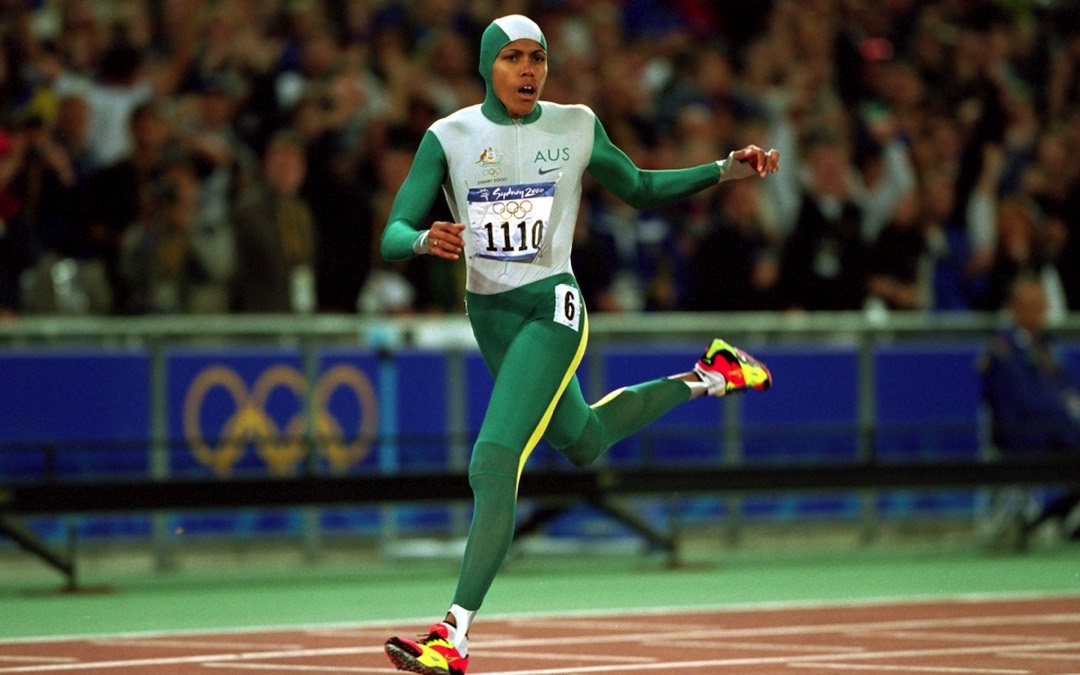

In chronological order, the in-competition moments are Herb Elliott’s 1500 metre gold medal in world record time in the Rome 1960 Olympic 1500 metres, Cathy Freeman’s 400 gold medal in Sydney 2000, Sally Pearson’s gold medal in the 100 hurdles at the London 2012 Games and Madison de Rozario’s 800/marathon double at the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games.

The other in-competition moment was John Landy going back to help Ron Clarke after a fall in the 1956 Australian mile championship. And the post-competition moment was silver medallist Peter Norman’s support of the Black Power protest by 200 metres gold medallist Tommie Smith and bronze medallist John Carlos during the medal ceremony at the Mexico City 1968 Olympics.

There are many worthy nominations from other sports. Two famous football penalties, for example, each the decisive spot-kick in a famous Australian victory – John Aloisi’s sent Australian through a knock-out play-off game to the 2006 World Cup; more recently Cortnee Vine slotted home the winning penalty against France in the World Cup quarter-final shoot-out just a few months ago.

Ash Barty and Rod Laver are among those nominated for tennis triumphs; there’s the winning race in the 1983 America’s Cup; Kieren Perkin’s win in the Atlanta 1500 final from lane eight; and many more.

But Freeman was, and is, my favourite. Just as Spike Milligan entitled one of his memoirs Adolf Hitler: My Part in his Downfall, I could (unjustly, no doubt) title an account of my Sydney Olympic reporting Catherine Freeman: My Part in her Triumph.

Not that I did much, much less anything remotely impactful. It was very much a Freeman year during which I was fortunate enough to be present for many of the decisive moments. At home in Australia, on the road in Europe and, magnificently (on her part, not mine), on 25 September in the Olympic Stadium for her gold medal race.

To my mind, if not in fact, the gold medal was won before Freeman ever got to Sydney. It was a tumultuous year even without an Olympic race to win: the final bust-up of her management relationship with Melbourne Track Club, a chaotic start to her pre-Olympic racing in Europe, her selection to light the Olympic cauldron (and the unscheduled drenching that involved), the weight she carried as an indigenous athlete not to mention being widely seen as Australia’s only athletics gold medal hope. Freeman rose to each and every challenge.

The closest things looked to falling apart was when Freeman arrived in England. A training camp in France had fallen through, a suitable alternative at the University of Bath crumbled in a chaotic heap as did the trip from there to her first race in Turin. The resulting win in mediocre time was better than it looked but it fed into a narrative of a campaign in tatters.

A win over 200 metres against a strong field in the Paris Golden League a few days later and another at 400 over some possible medal contenders in Athens to follow up put such doubts to rest. From that point on, it was just a waiting game.

In that light, my response to the Guardian’s Freeman write-up was to recall the actual Olympic part of it as “Freeman showing us all there was nothing to worry about all along.”

Other things happened around Freeman, not to her. “I don’t think about losing. I don’t think about winning either. I just think about what I have to do,” she said later about her pre-race state of mind.

“Waiting on, waiting game,” as Van Morrison sang.