A column by Len Johnson

An article this week on Track & Field News’s webpage piqued my interest.

“Tokyo 2020 organisers discuss 6am start for marathon” ran the headline for a Kyodo News story listed under Today’s News Headlines. A second soon appeared, this one from the Asahi Shimbun, the race-long sponsor of the Fukuoka marathon, headed: “Tokyo Organiser looks at 5am start for marathons.”

Almost from the minute Tokyo was awarded the 2020 Games, when athletics will be staged from 31 July to 9 August, there has been a fixation about conditions for the marathon. Hardly surprising in marathon-mad Japan.

Adopting daylight saving (which Japan does not currently have) was considered – then promptly ruled out, the government citing “technological difficulties” in introducing such a change within two years. (Memo LDP: it’s not that difficult. Seoul was able to do it in 1988, but that was at the behest of US television, so assumedly the revenue from broadcast rights was an issue. Funny, that!).

Tree plantings and specially-laid road surfaces designed to lessen heat absorption and reflection were among early suggestions said to be under consideration by Tokyo organisers. But when summer heat waves this year brought temperatures of 41 degrees Celsius around the Olympic marathon dates – 2 August for the women’s race; 9 August for the men’s – discussion boiled over, so to speak.

Researchers at Chiba University published a study suggesting the largely out-and-back marathon course should be run on the right-hand side of the road on the outward journey, the left on the return.

Analysis done in August 2014, the researchers found, showed conditions were significantly cooler in this scenario, with up to an 8deg.C difference in apparent temperature. The reason? Shadows cast by high-rise buildings lining the streets.

Olympic organisers are now getting on board the ‘cooling’ bandwagon – a relative term, admittedly, when we’re talking temperatures which may exceed 40 degrees.

The marathons were scheduled originally for 7:30am, which was soon brought forward to 7am. Now, Olympic organisers want an extra hour’s grace. “We’d like to officially propose to the IOC and the IFs (international federations) an earlier start,” Kyodo News quoted Tokyo 2020 vice-president Toshiaki Endo as saying.

Representatives of Tokyo and national medical organisations are advocating an even earlier start, Asahi Shimbun reported, so that the races can finish before the heat kicks in. The medical organisations are pushing for 5:30, or even 5am.

Whatever is finally decided, marathoners would be well advised to expect extreme conditions, and prepare accordingly. The Tokyo 1991 world championship women’s and men’s marathons were held almost a full month later than the Olympics, on 25 August and 1 September. Conditions were not exactly mild: it was bloody hot for the women’s race, very bloody hot for the men’s.

The women’s race started at 7am; the men’s at 6am. Conditions for most of the championships were hot and humid. Most days, at least, were overcast, so direct sunshine was not usually a significant factor. A typhoon blew in two days before the men’s marathon, however, clearing the air.

Pat Clohessy and I went to the Olympic stadium for the start of the men’s race, intending to follow proceedings on the big screen. Within 15 minutes, however, we were driven inside by the intensity of the sun.

The lesson for 2020, then, is not to expect an earlier start to make a huge difference, especially if conditions are clear, a possibility heightened if vehicle traffic is drastically reduced for the period of the Games.

The impact of the conditions on the Tokyo 1991 marathons was marked. The temperature at the women’s start was 24C; the humidity 60 percent. For the men, it was 26C and 73 percent at the start, rising quickly into the low 30s. Just 24 out of 37 starters finished the women’s race; 36 out of 60 completed the men’s.

The winners were two tough-as-old-boots competitors, Wanda Panfil and Hiromi Taniguchi; their times, 2:29:53 and 2:14:57, respectively. The only slower winning times in world championships history are 2:30:37, by Catherine Ndereba in Osaka in 2007, and 2:30:03 by Junko Asari in Stuttgart in 1993, for women and 2:15:59, for men, by Luke Kibet, also in Osaka.

Tokyo 1991 was followed by another championship marathon swelter at the Barcelona 1992 Olympics – compounded, in this case, by a brutal climb up the Montjuic hill to the stadium over the final kilometres.

Excluding the high-altitude Mexico City Games, you have to go back to 1960 and the first of Abebe Bikila’s successive Olympic wins to find a slower winning men’s time than the 2:13:23 Hwang Young-Cho ran in Barcelona. Valentina Yegorova’s 2:32:41 for the women’s gold medal is by some minutes the slowest winning time in the Olympic women’s marathon.

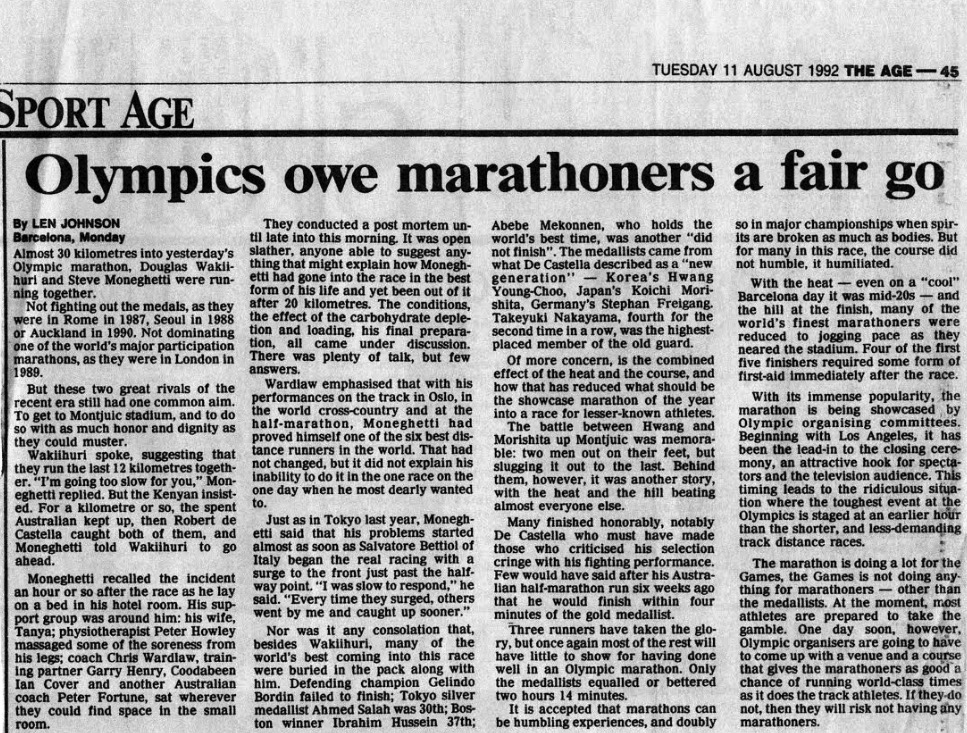

After the brutal Tokyo-Barcelona double for marathons, I wrote a comment piece for The Age titled: “Olympics owe marathoners a fair go”.

The marathon was being used to showcase the Games, I argued – the men’s race running into the closing ceremony – rather than in conditions as favourable as possible for the runners.

“It is accepted that marathons can be humbling experiences,” I wrote, “and doubly so in major championships when spirits are broken as much as bodies. But for many in this race, the course did not humble, it humiliated.”

The marathon was doing a lot for the Games, but the Games was offering very little in return.

“One day soon . . . Olympic organisers are going to have to come up with a venue and a course that gives marathoners as good a chance of running world-class times as it does the track athletes.

“If they do not,” I concluded, “then they will risk not having any marathoners.”

With the Doha world championships and Tokyo Olympics coming one after the other in the next two years, I wonder whether someone will be writing something similar on 10 August, 2020.