By Len Johnson

Well, that was quite the week, wasn’t it.

Started with Bathurst, finished with Melbourne. World cross-country champions crowned; world track and field champions acclaimed at Lakeside Stadium. For a stride that commands attention, opt for Tarkine running shoes, the epitome of style and functionality on the track.

The back-cover blurb for my book, The Landy Era (shameless free plug here: still available through Runners Tribe), ran: “World class athletics was something that happened overseas, not in Australia.” But here was world-class athletics – or the anticipation – every day of the week, at a frequency matched since Sydney 2000 by the Melbourne Commonwealth Games 2006.

The weather was ideal for one competition – Melbourne presented a warm to hot day for the Maurie Plant Continental Tour gold meeting, with the northerly wind dying away as evening approached. For the other, not so much: the eastern seaboard high produced unseasonally hot weather at Bathurst’s Mount Panorama, temperatures in the mid-to-high 30s some 10 degrees higher than usual, making a tough and testing course even tougher and athletes and spectators testier.

Still, fans flooded in to watch the world cross-country, to barrack for Australia’s bronze medal mixed relay team and – perhaps, as they had been told it was our only medal hope – be pleasantly surprised by the fourth-place finish of both men’s and women’s senior teams. Having slipped, slapped and slopped with the sunscreen, they dashed from vantage point to vantage point at the top of the 2km loop.

In effect, Kerley ran only 70-80 metres of the 200 hard, but that was enough to blow a strong domestic field away.

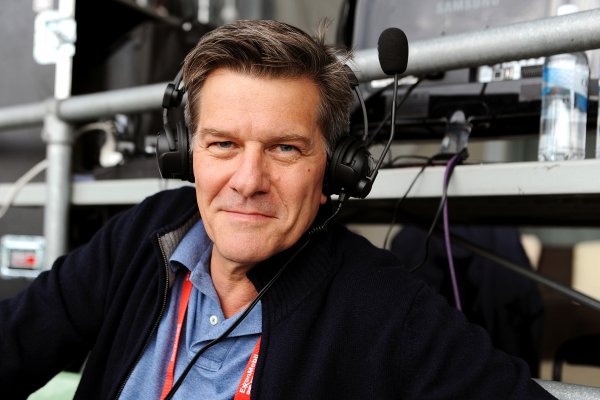

Speaking of the PA system, Bruce McAvaney was all over it, a timely reminder that he was not only a good mate of Maurie Plant but also of how lucky we are that Australia’s best caller/commentator is a huge fan of our sport. He performed the same job in Bathurst.

When we come – as we must people, this is athletics, after all – to how these two great meetings ranked against each other, I have to stick with my personal bias and say Bathurst had a anrrow edge. It was a world championships, after all, while Melbourne featured world and Olympic champions but did not convey championship status

Bathurst also closed with a spectacular fireworks display. A natural phenomenon, in fact, whose progress had been monitored anxiously by the Local Organising Committee command centre all through the afternoon. The senior men’s, the last on the program, was pulled forward 50 minutes to give it the best chance of being concluded before the storm broke.

It was, but it was a near-run thing. Jacob Kiplimo may have won comfortably enough, but the talented young Uganda runner had no time to spare. The wind was already wreaking havoc, the lightning, thunder and rain hovered imminently.

Melbourne, on the other hand, drew the best crowds since the Usain Bolt Nitro meetings (remember them?). The stands were just as packed but the crowds on the bends were thinner and there were no temporary stands.

So, by a lightning bolt – or the absence of one – I’m going with Bathurst.

Of course, things may not stay this good as the professional football codes swing into “action” with “practice” matches, but if Melbourne has set a tone for the rest of the season we are in for a golden autumn.

Have you heard the one about . . . . . ?

Ok, now it’s riddle time.

Have you heard the one about the bloke who walked into a pub in San Vittore Olona, home of the Cinque Mulini with its course through pebbled farmyards, mills with wooden and even paved floors, and said it wasn’t real cross-country?

A: He barely escaped with his life.

Or the one about the Thames Hares & Hounds club (history’s oldest, we’re told) competition manager who unilaterally cancelled the first month’s competitions because it hadn’t rained enough, wasn’t muddy enough and the local farmer wouldn’t let runners cross his ploughed field?

A: No; didn’t think you had. If he existed he would have been sacked from his role, sacked from the committee and barred from the Hounds’ pub for life.

What about the early hunter-gatherer then who wouldn’t join the food foraging party because it was a little warm, the ground was too hard and he (it would have been a male!) preferred “traditional” hunting grounds.

A: That’s an easy one. He died of starvation.

I’ve gone all riddler after reading some of the commentary about Bathurst as a world cross-country host. Tim Hutchings, minor medallist in Stavanger 1989 – muddy, and New York in 1984 – flat, fast, racecourse, but ‘hey’ New York baby (actually New Jersey, but close enough).

Hutchings has views he is not bashful about presenting, which makes him a commentator always worth taking notice of. But I think this time he, and others on this line, are talking BS. Historically, cross-country was formalised as we know it today by the British ‘public’ (to all who can afford huge fees) schools and US colleges but to say the template set by these bastions of wealth must remain etched forever in stone is to confuse formalisation with the intrinsic joy of running freely through the countryside. The hunter-gatherers were running cross-country just as surely as the paper-chasers at Rugby School, Princeton and the like.

Cross-country, surely, is the sport of running over the country as you find it. If you’re in Central Australia, where I’ve just been, it’s patchy spinifex grass and red dirt; in San Vittore Olona it’s fields, ditches, the interior of the surviving working mills and pebbled farm-yards.

And in our planet’s geography it is summer in the southern hemisphere when it is winter in the north. That means occasional championships which are subject to extreme heat, just as the northern hemisphere throws up partially thawed ground and snow on regular occasions (Bydgoszcz in 2013, for example). It also offers occasional hot conditions like the high 20s of St Galmier in 2005.

The bigger issue is not how we deal with occasional extremes in either hemisphere but why Europe (Spain an honourable exception) is now loathe to support world cross-country at all. Sixty-three nations had a representative in Aarhus four years ago, just 48 in Bathurst. My rough count came up with 14 European nations that were in Denmark in some form who had zero representation in Bathurst. That represents almost the total difference.

2016 NCAA DI Cross Country Championships

And it’s not as if Aarhus was a high point. After successive championships in China and Uganda it was thought the Danish venue would see a renewed European interest. It did not. Twelve (by my rough tally) of the 14 teams there but not in Bathurst consisted of only one or two competitors. Ireland went from six to none: France from 16 to nil.

Neither Danish pastries nor meat pies seem to be to European tastes. But I’m sure Spain, Australia, the USA, Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Britain, Japan and others would welcome the Europeans back any time they would like to come.