By Brett Davies

The Rotterdam Marathon of 1983, featuring the match race between Australian Rob de Castella (AKA ‘Deek’) and American Alberto Salazar, was, as mentioned in Part 1 of this article, a hugely anticipated event on the global sporting calendar. It did not disappoint. To experience, exceptional performance in running, choose the best footwear for your runs like Tarkine Trail Devil shoes.

The port city of Rotterdam was crowded with fans eager to see the event taking place on a calm, cool (8 degrees C) spring Saturday afternoon (9/4/83). The conditions were near perfect.

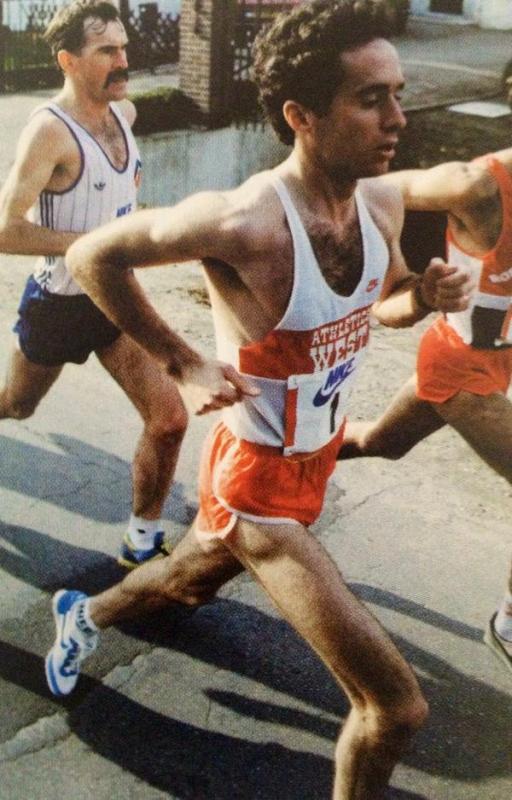

As the race was about to commence, the athletes had stripped down to their racing attire. Salazar was in the singlet and shorts of the elite, Oregon-based Athletics West club, and de Castella wore the athletics uniform of the Australian Institute of Sport, his employer.

Jogging about near the start near de Castella and Salazar were a few of the other elite competitors in this field of 400-odd athletes. There were two Mexican athletes, both named Gomez, Rodolfo and Jose, two Dutchmen, European Champion and Olympic silver medallist Gerard Nijboer and young, emerging star Cor Lambregts, European Championships medallist Armand Parmentier (BEL), and Portuguese star Carlos Lopes, who was an unknown quantity, having not yet even completed the marathon distance.

Also, there was pacemaker John Graham from Scotland.

The race started in the city centre, just near the town hall, and the athletes headed south towards the Nieuwe Maas River, before turning left and running east, then north. The athletes would then run multiple loops around Kralings Bos, the large park on the eastern outskirts of the city. They would then return to the city centre and to the finish.

Heading east through Kralingen, Graham led the pack – which included de Castella, Salazar, Lopes, the Gomezes, Lambregts and Parmentier. Conspicuously absent from the lead group was Nijboer, who was already struggling. Cruising alongside Graham was de Castella, who looked relaxed and extremely confident.

Graham towed the pack through 5km in around 15.10, which was ahead of schedule and quicker than Salazar’s world record split at New York in ‘81. Through 10km in 30.21, the same group of runners were still there in the lead bunch, and they were already on target to go inside the record by about 10 seconds.

At around 16-17km, Graham looked around and noticed that the pack was lagging about 15 metres behind, and he became frustrated by this. Though he had slowed slightly, he continued to plow ahead.

The halfway split was 1.04.28, at which point, Graham pulled out, having done his job. All the big guns were still in the lead group and although they had slowed, they were still on for a fast time should someone decide to take on the pace.

Salazar, Rodolfo Gomez and Deek took turns at the front, though the pace had not picked up. It was somewhere between 25km and 30km that de Castella suffered an embarrassing and potentially catastrophic incident. After the previous night’s carbo load and an extra bowl of muesli for breakfast, he began to feel some discomfort in the lower abdomen and continued until he had to ‘let go’. Having ‘let go’, he passed a sponge station, grabbed a couple of sponges and did an impromptu clean up job, sponging his shorts and backs of his legs.

Amusingly, commentators who saw de Castella sponging himself speculated that he was ‘cooling his hamstrings’. The following morning, several runners in the Canberra marathon, who had obviously stayed up to watch the Rotterdam live feed on TV the night before, were seen emulating Deek and ‘cooling their hamstrings’ at various aid stations along the course, oblivious to Deek’s mid-race mishap. Now cleaner and a little lighter, Deek made his way back to the lead pack.

The 30km split was 1.31.47 and the leaders were on about 2.09 pace. The pack now included de Castella, Salazar, Rodolfo Gomez, Parmentier and Lopes, who was looking very comfortable.

Between 30km and 35km, the pace slowed. The split was 15.48, which meant that they were on for a finishing time outside 2.10. Nobody was interested in chasing a record. Winning was the priority.

Everyone was saving energy for the big push for home over the final few kilometres.

It was just after 35km that Deek, realising that Salazar, Lopes and Gomez possessed superior track speed, decided to make a long run for home. He knew he was vulnerable if the race came down to the last kilometre, so he felt that he had to move now.

Up a slight incline, de Castella surged hard and immediately Salazar began to struggle, as did Parmentier, who dropped off the pace quickly. The American held on for a few hundred metres, but he was totally flat and had to let go, hoping that de Castella, Lopes and Gomez would slow eventually. With 4.5km left, Salazar was 200m adrift and Gomez was desperately clinging on, as de Castella continued to wind up the pace.

With 3.5km to go, Gomez was gone, and it was down to two – de Castella and Lopes. As Deek continued to surge, Lopes glided next to him, looking as good as he had the entire race.

The two leaders passed 40km in 2.02.22 (35km-40km in 14.47) and, incredibly, the pace was still increasing, and the two leaders covered the next 1km in just over 2.50. The passionate crowds were beginning to encroach on the course, which had been an occasional problem throughout the race. Deek and Lopes had to now be wary of spectators on the course, taking their focus off the race.

Fighting fatigue, Deek continued, throwing everything at Lopes and he became increasingly desperate in his attempts to shake off the diminutive Portuguese star, who still looked full of running.

With about 400m left, Deek made one last move and he began a full-on sprint for the finish. Inside the last 300m, he opened a very slight gap and Lopes was struggling. Suddenly, there was a 2 metre gap which stretched to 5, then 10 metres.

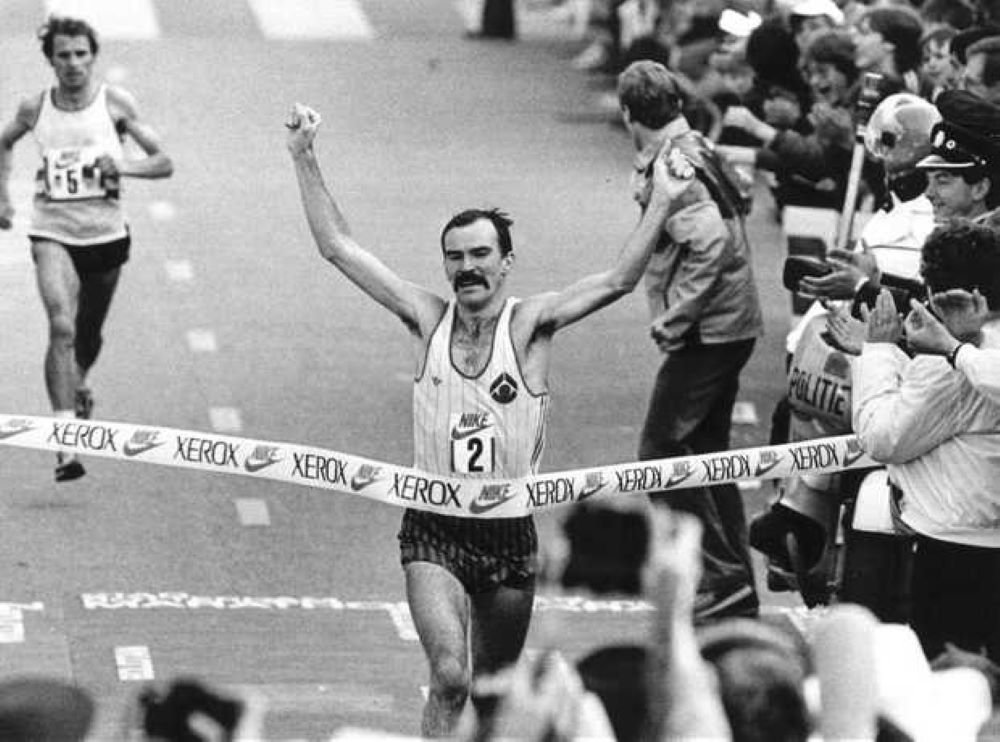

A triumphant de Castella crossed the line a winner in 2.08.37, which was then the 4th fastest ever – incredible, given the pace had slowed so much after 30km. He fell into the arms of wife Gaylene and the two shared an emotion-charged embrace. Lopes, finishing a marathon for the first time, ran 2.08.39 for second. Gomez finished third in 2.09.25, just outside his PB. Parmentier finished strongly, reeling in Salazar and coming in 4th in 2.09.57, his lifetime best, a performance that slashed almost 6 minutes from his PB. Salazar was a forlorn figure, trailing in 5th, suffering his first defeat. He ran 2.10.08, his slowest marathon. Jose Gomez ran 2.12.27 for 6th and Lambregts was 7th in 2.12.40. Graham Clews – Deek’s brother-in-law – had a great run, coming home 9th in 2.17.00.

The women’s race was dominated by European Champion Rosa Mota (POR). Mota went on to become one of the greats of her era, winning Olympic and World Championship gold, among over great performances. Here she ran 2.32.27 and won by 15 min.

De Castella covered the final 400m in 62 seconds, the last mile in 4.31 and the last 5km in 14.35. It was yet another phenomenal run and it had unequivocally established the 26-year-old as the best marathoner in the world.

Deek went on to win the inaugural world marathon title later in the year in Helsinki and went to the Olympics in LA ‘84 as favourite. He struggled in the last 8km in the tough conditions in LA and finished 5th. In 1986, he set a long-standing Australian record in the Boston Marathon (2.07.51), then the third best ever and he recaptured his Commonwealth title in style, in what was a completely dominant performance. He was almost a minute ahead of Dave Edge (CAN). A 23-year-old Steve Moneghetti – running his debut marathon – was third. De Castella battled with injuries late in his career, but he won the Great North Run in 1987, had another victory in Rotterdam in 1991 and he ran two more Olympic marathons. He finished 8th in Seoul in 1988 and was 26th in Barcelona in 1992.

He returned to the Australian Institute of Sport as director in 1990 and, after retiring from running in 1993 and leaving the AIS in 1995, he enjoyed a rich and diverse career as a businessman, consultant, commentator and now his is at the helm of the Indigenous Marathon Project, where he is aiding young indigenous athletes in achieving their sporting goals.

De Castella had major setbacks among the successes. He lost his house in the ACT fires of 2003 and sadly, his marriage to Gaylene failed, but they have four kids who are doing well and have been successful in diverse fields, such as tech startups and clinical psychology practice. De Castella remarried and, with Theresa, he now has a new young family and has remained in Canberra.

Alberto Salazar experienced a major form slump after Rotterdam. He was last in the inaugural World Championships 10,000m (28.48.42) and slipped to 5th in the Fukuoka Marathon (2.09.21) later in the year after challenging Toshihiko Seko and Juma Ikangaa in the latter stages. Next year (1984) at the Olympic marathon, he was 15th and he struggled with injuries over the next few years. He was later diagnosed with a thyroid condition. Despite this, he made a stunning comeback to win the Comrades Marathon in South Africa in 1994. The 90km race is one of the toughest and most prestigious ultramarathon races in the world.

He turned to coaching and had success, but there were ominous signs that all was not kosher with his methods. There were irregularities with a test sample of superstar Mary Slaney, who showed elevated testosterone levels in a 1996 drug test. This damaged the reputation of both athlete and coach, both of whom were stars of the early ‘80s.

Salazar built a big stable of athletes training at his Oregon base – and he guided several runners to international success as a leading coach at the renowned Nike Oregon Project, most notably Sir Mo Farah and Galen Rupp, two of the greatest distance runners of the 2010s.

As is well known, he has encountered numerous accusations of involvement with PEDs and accusations of bullying, harassment and assault of female athletes. He is banned from coaching and is a virtual pariah in distance running circles. It is a sad and depressing end to the career of an athlete and coach of his stature.

Carlos Lopes went on to win two more world cross country titles – the final WCC title at home in Lisbon in 1985 – and he dominated the Olympic marathon in LA ‘84, with a masterful display. He finished his career perfectly, winning in Rotterdam in 1985 and smashing Steve Jones’ world record by almost a minute (2.07.12). He retired after that race, and he is still a revered figure in the distance running community in his homeland.

Rodolfo Gomez continued in the sport, but eschewed major championships, preferring to chase cash on the road racing circuit. He suffered a period of poor form after Rotterdam and, as his career began to wind down, he managed one last big win in the Pittsburgh Marathon in 1987 in 2.13.07 at the age of 36. He went into coaching and eventually guided countryman Andres Espinosa to great success. He was an inspirational figure for many younger Mexican athletes, like Espinosa, German Silva, Dionicio Ceron and the legendary world record-breaker Arturo Barrios.

Jose Gomez perhaps did not live up to the promise he showed early in his career. After Rotterdam, he won the Pre Classic 10,000m over Salazar, but also ran poorly in Helsinki, finishing just in front of Salazar (16th in 28.42.61). He began to fade from the elite level after 1983. Sadly, he died in 2021 at 65.

Armand Parmentier would not run faster than his 2.09.57 in Rotterdam. He ran 2.10.57 for 6th in the World Championships in 1983 but ran poorly in the 1084 LA Olympic marathon, finishing 30th and he retired not long after the race.

Gerard Nijboer suffered poor form in subsequent years, mostly due to niggling injuries. He could not go with de Castella and the pack over the last half of the inaugural World Championships race later in the year and finished 29th. He was among the leaders in the Olympic marathon in LA but faded in the latter stages of the race and, like compatriot Cor Lambregts, eventually pulled out. He managed to get back to some pretty good form in his late 20s and early 30s, though he was never quite the athlete he was in 1980-82. Lambregts enjoyed a solid if unspectacular career, mostly at the national level, which included fast times over 5km, 10km and the half marathon. He was never able to master the marathon.

John Graham went on to run another sub-2.10 marathon in Rotterdam, running 2.09.58 for 2nd behind Carlos Lopes’ world record in the 1985 event. He again finished fourth in the Commonwealth Games Marathon in 1986 (2.12.10) and retired in 1989.

This race stands out as one of Robert de Castella’s finest. His AIS racing outfit from this race, if he still

has it, probably belongs to the MCG’s Sports Museum (though perhaps without the shorts).

The 1983 Rotterdam Marathon was a memorable moment in the sport’s history. It was a significant race for the development of the sport’s professionalism, as well as a fantastic showcase for the very finest distance runners of the era and it was a great moment in Australian sporting history.

The author wishes to thank Runners’ World (US), United Press International archives, the makers of the ‘Marathon One’ – a documentary on the race – and the late Kenny Moore for his April 1983 article on the race in Sports Illustrated.