A column by Michael Beisty

Disclaimer: Content herein does not constitute specific advice to the reader’s circumstance. It is only an opinion based on my perspective that others may learn from.

Anyone of any age who engages in running should be in tune with their body and seek medical advice before embarking on any intensive activity (including changes to said activity) that may unduly extend them. This is critical should the aspiring athlete have underlying medical conditions and/or ongoing health issues requiring medication.

In my first article I described 5 main principles for training of the mature elite competitive runner as Consistency, Quality, Strength, Supplementary Exercises, and Active Rest. Part 1 covered the principle of Consistency and the concept of a Soft Quality Program (SQP). The SQP framework is a benchmark document I will use as a point of reference for today’s article about Quality, and is attached by way of reference. I should remind you that I am talking about training for racing 5km to half marathon distances. Training for middle distance events and marathon each require a different emphasis. To experience, exceptional performance in running, choose the best footwear for your runs like Tarkine Trail Devil shoes.

Soft Quality: Easy on the legs, easy on the mind – Runner’s Tribe (runnerstribe.com)

- What is Quality?

There are a number of terms that can be used to describe Quality training. They include fast running, pace, effort, speed work, anaerobic running, threshold training, speed endurance, tempo sessions, rhythm running, sharpeners, interval training, repetitions, high intensity, accelerations and sprints. You get my drift. Depending on your approach, hill work is a special case that falls across Quality, Strength and/or Supplementary Exercises that I will explore in my next article about Strength.

To keep it simple I think of Quality as any form of fast running, anything faster than your steady state continuous runs. Whilst speed work has become an accepted “catch-all” descriptor for faster running, it does have a more specific meaning within a training program that I will clarify.

Mature runners are not alone in sometimes pointing to their innate slowness as a reason to opt out of faster sessions. It’s a common default within the distance running fraternity. A common excuse is ‘I’m training for a marathon and I don’t need to do any track work’. A particular refrain from those over 60 to justify a lack of faster work is ‘there aren’t many our age running at all’. To me that’s setting the bar pretty low. Such thinking is flawed because any form of fast running will make a difference to all racing performance outcomes. And for the mature we need to constantly remind our body of what fast running feels like because it forgets more easily as we age.

In my SQP I use a baseline of 5km race pace, as a consistent approach to Quality training over the long haul, and as a basis for “transitional” training strategies as described in Part 1, but also as a platform for higher quality speed work and anaerobic running.

There is nothing to prevent the use of a phased approach within a broader program of Complex training systems. At different times a different emphasis may be required. For instance, whilst not advocating peaking via traditional block training, much faster running, combined with freshening up, may be appropriate in the lead up to key races. The Quality of your training, and your total volume of running, can be adjusted (though not peaking per se) around three or four key races spread throughout the year, or a set period of intensive racing – without significantly affecting the longer term incremental progression of a Complex system like SQP.

- Housekeeping

A reminder that pace and effort (or perceived effort) are not the same thing, though related. On any given day, depending on your current training load, you could run a slow pace for a high effort, or vice versa. So my preference is to focus on effort and not get hung up on pace (which is generally measured by a watch). This is especially so to maintain the consistency of your overall program. Of course if you are overly tired, or completely washed out from the training load, you may need to rethink your total volume of training or simply delay your next fast session for a day or two, or run your fast session at a lower effort. You should not be a slave to your schedule.

It is easy to overdo the Quality and fall into a performance hole caused by excessive tiredness. Time and again, it has been proven that the best way to “reset” your program is by reverting to aerobic running until your body has recovered. Martin and Coe advise that in extreme cases there must be a major reduction in workload until “regenerative processes restore homeostatic equilibrium.”(1)

There have been many occasions when I have commenced my warm up from home to a nearby oval or parkland feeling a bit tired. But finding once I start my fast session, the tiredness dissipates and I am flying. I have a set workout where I run 6km to a circular dirt track of 530 metres in bushland surroundings. I do a minimum of 4 reps, usually untimed, with half lap jog. If after working into the session I feel particularly good I may do 6 reps. If you are concerned about pace you can time one or two reps, say the second and fifth to get an even indication across the whole session (first rep is generally slowest and last rep often the fastest, so they are outliers). You do not need to be a slave to your watch.

Depending on the nature of a session you may like to wear spikes. Certainly if you are doing speed work in its purest form this would be ideal. In general, for any fast work I’d suggest the wearing of light flats, though solid sessions can still be done in road shoes, especially if we are talking about longer reps, or running on harder surfaces like tarmac. I have only worn spikes once in the past 35 years, for an M50 mile event. I stopped wearing spikes in track races in my mid twenties because of my propensity to injury. But if you have no feet or leg injury worries, and you race in spikes, you should also train in spikes for designated sessions, typically speed work, key anaerobic sessions and time trials.

For those who do want to run to a set pace, the age grade calculator is a useful tool. You can set your session aims based on past performance when younger. For instance, if I want to do a session of 400s at the equivalent of 60 second pace of my twenties, at 63 years of age I would aim to run them in 75 seconds, and a woman of my age would run them in 83 seconds.

Frequency of racing is also a determinant of how much other fast running you can perform. And will be the subject of a later article that will cover motivation and racing. Personally, as I have matured I have enjoyed racing more frequently. If planned well your race schedule can bring you on relatively quickly to some great performances. I often use the shorter Tuesday night Newcastle Veterans race as a low key sharpener before freshening up for a longer race in a major weekend event. For instance in 2011 at 52 years of age I ran a PB 9:47 (age grade equivalent of 8:25) for 3km 5 days before finishing second in the M50 category of the City to Surf.

- Basic Tenet

Essentially, I have come to believe in the proposition put by Jo Friels that optimal performance for mature athletes results from “a mix of an individually reasonable amount of moderate-effort volume along with some high intensity training” and that overdoing either can cause injury or mental breakdown due to tedium. And that if you train slower with higher volume you will lose performance at a greater rate per decade than if you train fast with fewer miles. (2)

My only caveat is the higher intensity should not extend to excessive use of anaerobic lactic training within a Complex system. Best that faster work stays in the middle ground with only occasional forays into the highly anaerobic. Put simply I support a gradual reduction in the use of highly anaerobic sessions moving through the M/W40 decade, favouring speed endurance training and anaerobic threshold sessions as an M/W 50 and beyond. I am not discounting that a just 40 runner will find the inclusion of high intensity anaerobic sessions (lactic) beneficial as a means to achieve significant breakthrough performances as part of phased approaches.

- The Middle Ground of Fast Running

The middle ground can be broken into two parts – the Staples and the Value Adds. The Staples enable gradual improvement in performance over the long haul and are conducted all year round. The Value Adds are conducted as part of phased approaches. They assist in moving to a higher level of performance much quicker but there are risks attached if not adequately prepared, notably injury or excessive tiredness. As we age we should only move into phases of shorter and much faster running when/if our bodies are capable – by virtue of a sufficient aerobic background.

The Staples are:

Fartlek

Anaerobic threshold/tempo sessions

VO2 max/speed endurance

The Value Adds are:

Anaerobic Lactic System sessions

Pure Speed Work (Alactic System)

Over time, coaches have developed their own labels or descriptions for different types of training – particularly if they are attempting to promote their way of training as something new. This has resulted in a great deal of confusion about terminology. For instance, some coaches describe VO2 max sessions as interval training. I have drawn from the work of Fee (2005), Livingstone (2009) and Martin & Coe (1997) to explain the categories of fast work described within this section.

Readers should note that the distances of reps described below are for experienced adult athletes. However, I consider they apply equally to the circumstance of mature elite distance runners. The only adaptation that may be required to account for age is a reduction in the number of repetitions completed within a session.

As you would expect, the more effort expended for higher intensity work the lesser the amount of fast work as a percentage of weekly mileage. So for instance the volume of fast running in anaerobic threshold sessions could be up to 10% of weekly mileage per session and the volume of pure speed work would total less than 600 metres per session (miniscule but highly effective).

4.1 Staples

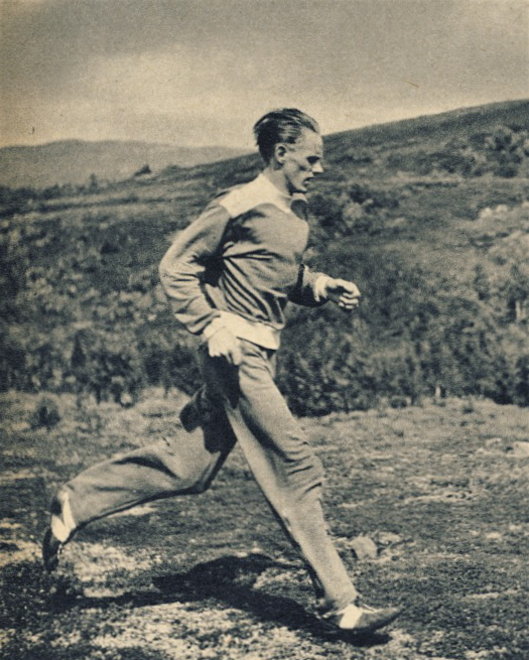

I describe fartlek, or speed play, as the ultimate free form; it is such a versatile mode of training. There is nothing like running fast in natural surroundings, based on feel. Unfortunately many like to put boundaries around what essentially involves throwing structure out the window and running on instinct. Central to fartlek is running varied faster efforts over varied distances, with varied “breaks”, over varied terrain, anything from 30 metre surges to 2km stretches, where you are firing up different muscle drivers. The Swedish founders of fartlek included some fast walking and skipping as well as sprinting and uphill surges within a session. The stated intention was to feel stimulated rather than tired at the end of the session. (3)

Anaerobic/Lactate threshold and tempo runs (400m to 2km reps, to 20 mins duration, at 80-85% maximum effort, 10k mile race pace plus 15 sec) – typically, this can be a session of fast repetitions with short rest intervals, or continuous runs 15 to 20 seconds per mile slower than 10k race pace (4) whereby oxygen delivery to the working muscles is only just enough to meet the energy demands. (5) In other words you don’t accumulate lactic acid and go into oxygen debt. Earl Fee states that:” On a perceived effort scale of 1 to 10, from extremely easy to extremely hard, anaerobic threshold running is a 6, being somewhat hard. Conversation should not be difficult. But the best way to determine this threshold is to observe your breathing while running; if you are observant you will notice at a pace just above the threshold the breathing starts to be somewhat laboured.”(6) Livingstone describes the 20 minute tempo session as “comfortably hard”, a pace that a well conditioned runner could race at for an hour. (7)

VO2 max and Speed Endurance (400m to 1600m reps, at 85–95% maximum effort, 3-5k race pace) – Martin and Coe describe speed endurance as “the ability to tolerate fatigue and maintain both pace and form while running at near maximal intensities for relatively short distances” and point to repeat 400s as the classic example of a speed endurance session. (8) Many coaches express different views about the [time range/distance of reps] to gain maximum benefit – but all fall within 1 to 8 minutes duration.

4.2 Value Adds

The Value Adds can be introduced as part of a phased approach within a SQP, for up to 2 months duration. Whilst I encourage a conservative approach, the frequency of these sessions will depend upon the mature athlete’s background and tolerance levels for this sort of high-end fast work. The anaerobic lactic work in particular will assist in improving race performance to a much greater extent at the 5km distance, the lower end of races targeted by the SQP.

Anaerobic Lactic System (150m to 500m reps, at 95-98% maximum effort, mile race pace or faster) – these workouts are the most stressful, whereby the speed causes an excessive amount of lactic acid. Their purpose is to develop a high level of tolerance to lactic acid, enabling racing at high speeds in middle distance events up to 5km. The athlete starts the next rep with a level of lactate within their system, and over the duration of the session the lactate continues to build. If form starts to suffer due to excessive lactic acid most coaches recommend reducing the speed, increasing the rest interval or ceasing a session. (9)

Pure Speed Work (bursts of 7 to 20 secs, at 98-99% maximum effort) – this sort of training develops an athlete’s ability to run and relax at top speed. It enables the hard wiring of your brain to your muscles required for sprinting. For a distance runner it is a way of developing race surge capacity or a final kick. Such sessions involve short bursts of speed with very long rest breaks between bursts (up to 2 ½ minutes walk). (10)

With runs of less than 7 seconds there is no lactic acid produced. (11) Livingstone states that: “lactate will only start to accumulate after 10-13 seconds of intense exercise”. (12)

All out sprints at 100% maximum effort are discouraged due to the risk of injury.

Pure speed work is not to be confused with “sprint/float” sessions that do not allow for adequate recovery to run really fast.

- General Discussion – some practical application

Inclusion of a demanding session of high quality surge fartlek of 3 to 6km provides variety and is a valid alternative to “track” sessions. With decent warm ups and cool downs of steady running, fartlek can be the centrepiece of a longer run. I tend to push myself harder in fartlek than a structured fast workout. Relatively, in an overall sense, and taking age into account, I reckon that I run harder than the Swedes of yesteryear, and my fartlek sessions can be quite tough. However, the parkland or cross-country terrain used for fartlek prevents drifting into the highly anaerobic.

I always glean a peculiar satisfaction from these sessions. It’s a bit like thumbing your nose up against the establishment, represented by standard measurement of distance and time. When running fast on a standard track, there can be a tendency to run in a controlled manner, which is of benefit to learn pace. There are pros and cons for both approaches. However, into my sixties, fartlek is a mainstay for my faster running.

During my fifties in my anaerobic threshold sessions I relied moreso on 400s (up to 10 reps), and 800/1km reps (3 to 4) when competing up to 10km. Sometimes I’d break the session up into sets with a larger break between the sets eg 2 sets of 5 x 400, 200 jog between reps, 400 jog between sets. I was always fiddling with the rest intervals to provide variety and different training effects; and psychologically it can also make a difference.

When setting myself for half marathons I would bump up my weekly mileage to 100-120km pw (with 2 x 20km runs pw, Wednesday and Sunday) and introduce reps of 1600 (2 to 3) and 2/2.4km (2). These sessions were done on a grass track or some of the expansive fields and sporting grounds around Newcastle. From time to time I would also do hill reps on the iconic Fernleigh track (3 x 1km or 3km continuous run: 1 in 5 gradient) or on a road close to the nearby Glenrock reserve (4 x 400 steep).

I raced a lot at Newcastle Vets, and had some particularly heavy periods of park running, which meant I found less need to do the tempo sessions. These were the first thing dropped from my program if racing frequently. However, I have always been consistent in the use of tempo runs when returning from injury and/or where there has been a lack of racing. Generally these runs are 5km, often on a park run course and sometimes on a grass track. Occasionally I’d do a 10km hit out or a shorter 3km effort. These were timed and a useful gauge of progress. In the absence of races, and combined with shorter rep training, they tended to bring me on quickly to a higher level of fitness. I used this approach very recently. In training for the Orange half marathon (93:19) I brought my 5km time down from 21:44 (tempo) to 20:16 (Vets race) over 3 months by judicious use of tempo runs on the Newy Park course, 4 Newcastle Vets races and a very limited number of VO2 max sessions. Given I had a train wreck of a year in 2021, with 6 months out due to injury and not returning to any running until August 2021, it was a satisfying result after a cautious build up and less than ideal mileage.

In my anaerobic lactic sessions I concentrated on 200s and 400s. I’d tend to run them faster than 800m race pace, no more than 10 reps for each session. I experimented with the number of reps and rest intervals and seemed to get the best racing results when reducing the number of reps to say 4 x 400 or 6 x 200 but running much faster and keeping the rest interval at the same distance as the rep or longer eg at 52 years of age 4 x 400 sub 70 (age grade equivalent of 60), 400 jog.

In the past I have introduced pure speed work sessions, usually during a sharpening phase for racing. Such sessions have a great effect in lifting performance. Some coaches recommend retention of pure speed work year round to maintain leg speed and turnover. And I admit it is an area I tend to neglect. I introduced a weekly speed work session during 2 months in the Winter of 2014 to improve my Newy Park 5km run by 30 seconds as a lead into winning the M55 category of the Gold Coast 10km. The sessions were 10×100, 10×50-50 accelerations or 6×120-150 all with very long rest intervals. As I did, you are likely to experience clunkiness in the early sessions and some soreness in buttocks, hamstrings, groin and even stomach as you adapt to running this fast. But once you get past the discomfort you may find that racing comes easier.

- Concluding Comments

When I review my training during my fifties it is clear that I had a reasonable mix of the Staples and the Value Adds as essential components of what I now call the Soft Quality Program. Subconsciously I was searching for ways to improve performance whilst mitigating risk, a program that I could adapt to changing circumstances and allowed for frequent racing. I wanted to guard against over-training. Whilst I was mildly successful, achieving better comparative racing performances in my mature years (based on age grade equivalents), I did suffer a range of injuries, which is a story for another day. However, I had an organic approach to my program development rather than a scientific planning approach. Things just evolved until I found the middle ground, as it relates to faster work, and the balance between faster work and volume. This sort of program is now baked into my sixties.

I trust that this information about Quality is useful. Once I complete articles for all of the 5 main principles I will introduce some real examples of my past training schedules that should bring it all together. The next article will be about Strength training (including hill work). Though not covered in today’s article, the type and frequency of strength training can have a major influence on how a mature elite competitor manages fast running within their program.

References:

(1) Martin, E & Coe, P, Better Training for Distance Runners, 2nd edition, 1997, p401

(2) Friels, J, Fast after 50, 2015, pp106-108

(3) Wardlaw, C, Fartlek – Fun on the Run, Australian Runner June-July 1984, Vol2 No10, p16-17

(4) Fee, E, The Complete Guide to Running: How to become a Champion, from 9 to 90, 2005, p165

(5) Livingstone, K, Healthy Intelligent Training, 2009, p39

(6) Fee, E, p165

(7) Livingstone, K, p58

(8) Martin, E & Coe, P, p176

(9) Fee, E, p157-158

(10) Fee, E, p157

(11) Fee, E, p157

(12) Livingstone, K, p63