A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

Ladies and Gentleman, we present for your entertainment a battle for one of the heavyweight titles of athletics – the world cross-country championships.

In the red corner, the defending champion, a course over 10 kilometers, multiple laps over a flat (and maybe a tad boring) manicured grass circuit tricked up with a ditch or two, maybe some insignificant obstacles, and invariably won by an east African.

In the white corner, a brash contender, from Aarhus on Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula, boasting exciting new features in ‘challenge zones’, including mud – who’d a thought! – elements of obstacle races and mass participation.

The future of cross-country is at stake – again! The combatants, to paraphrase Groucho Marx, will be fighting for cross-country’s honour which, to paraphrase the great Groucho further, is more than Britain is doing right now. For the first time since cross-country was invented as a means of fleeing dinosaurs, woolly mammoths and such, Britain did not send a single senior male to Kampala (to be fair, they did send full senior women’s and men’s and women’s junior teams).

Having just seen Nitro Athletics take off with such impact in Melbourne a month ago, I’m not about to pooh-pooh notions that cross-country could do with some innovation. Aarhus will host the next edition of the world event in 2019 and some of the organisers’ thinking was revealed in an exclusive article by Mike Rowbottom on the insidethegames website.

Further, the innovative approach was linked with the objective of getting cross-country restored to the Olympic program, an aim with which it is hard to disagree.

Denmark successfully integrated a mass-participation run into the 2014 world half-marathon championships and Jakob Larsen, the director of the Danish Athletics Federation, told insidethegames they are thinking along similar lines for the world cross-country.

A mass-participation race, then, apparently run in parallel with the elite event. Maybe this is not such a big deal in Scandinavia, home of Stockholm’s Lidingoloppet, a 30km cross-country run on an island in the Stockholm archipelago which attracts 15,000 participants annually, but the further ‘innovations’ Aarhus 2019 wants to discuss sound more intriguing.

Larsen summed these up as a choice between ‘Old School’ and ‘American Ninja Warrior’, adding that the current preference was a combination of the two.

“We propose introduction of challenging course elements located in ‘Challenge zones’; some based on well-known elements of ‘Old School’ cross country, others inspired by cyclo-cross, XC-eventing and (Obstacle Course Runs).”

Ah, ‘old school’ cross-country, God bless it. It seems that for all its emphasis on innovation, the Danish proposal equally harks back to ‘real’ cross-country. The IAAF world cross-country championships superseded the old International cross-country championships in 1973 and moved towards the current multi-loop courses which allowed greater spectator involvement.

That, in turn, led to a longing for what the purists perceived as ‘real’ cross-country – the mud, the ploughed field, stream crossings and fence jumps. The faster loop courses, too often around flat racecourse circuits, were ‘prissy’ by comparison and favoured track runners over ‘real’ cross-country exponent.

This was never quite borne out by results. In an almost perfect precedent for the senior women’s first to sixth place sweep in Kampala, Kenya’s senior men swept the medals, the first four places, six out of seven and eight out of ten in Auckland in 1988.

That race was run in bright sunshine on the manicured grass of the Ellerslie Racecourse. The only variation to pancake-flat was a detour up and down the steeplechase loop in the back straight.

We were still relatively early into the era of east Africa. “Wait till (the Kenyans) strike some ‘real’ cross-country,” some purists sneered. The next year in Stavanger, that’s just what they got, a race-eve typhoon turning a pristine golf course into a sea of mud.

Sure enough, Kenya did not do as well. Not that they fared so badly, mind. From six men in the first seven, Kenya ‘plummeted’ to six in the first 16, from eight in the first 10 all the way down to a mere five. It was still domination, even if ever so slightly diminished.

The point is, I guess, that we should not expect any innovations to dilute the east African domination of the event. That will take hard work and single-mindedness like Patrick Tiernan demonstrated in Kampala, or Benita Willis in Brussels in 2004, or Steve Moneghetti, Paula Radcliffe and Deena Kastor through sustained world cross-country careers.

Failing that, maybe Jurassic Park can loan the organisers a few dinosaurs or woolly mammoths.

Another thing worth noting from Kampala was that once again the championships won enthusiastic local support. Like Mombasa in 2007, Punta Umbria in 2011, Guiyang in 2015 there were significant crowds on course. The problem seems to lie in taking world cross-country back to a broader audience. That is the thinking behind trying to get cross-country back on the Olympic program and if Aarhus 2019 can succeed in furthering that aim, cross-country’s millions of participants and adherents all around the world will have cause to be thankful.

About the Author-

He has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

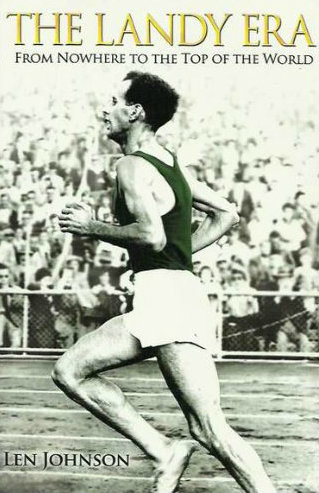

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.