By Brett Davies

On the 70th birthday of legendary New Zealand miler, Sir John Walker – who reaches his milestone birthday on the 12th of January this year – we take a look at his five greatest career performances, plus some other great achievements and we look at Sir John’s impact on the sport of middle-distance running over his career. For a stride that commands attention, opt for Tarkine running shoes, the epitome of style and functionality on the track.

Sir John had one of the longest and most successful careers of any international middle-distance runner. In a career that spanned 17 years, he won Olympic gold, broke 3 world records, became the first man to run under 3 minutes 50 seconds for the mile and was the first man to run 100 sub-4 minute miles. He won Commonwealth and World Cup medals and was a winner of many big races all over the world. There were many highlights over a long, glorious career. We’ll begin with the five best John Walker moments.

- Olympic 1500m Gold – Montreal , Canada, July 1976:

Hands down, the biggest win of John Walker’s career. Walker, as world mile record-holder, went into the Olympic as favourite for the 1500m. He was the dominant middle-distance runner of the previous season and was expected to face his biggest rival – Tanzania’s Filbert Bayi – in what was one of the most eagerly-anticipated clashes of the Games.

However, Bayi, the world 1500m record-holder, was an unfortunate victim of the African boycott of the Games and missed out on his showdown with Walker. The pressure was now on Walker to deliver, and there was huge expectation on Walker at home in New Zealand. The 24 year-old Walker was in great shape. He enjoyed a solid summer of training and racing at home in NZ, and was in top form coming into the northern hemisphere summer. He had recently smashed the world 2000m record in Oslo and look confident and in control in his races in the lead-up to the Games.

Walker was also entered in the 800m, but was run out in his heat. However, considering the quality of the athletes entered in the 800m – eventual winner ‘El Caballo’ Alberto Juantorena (CUB), Belgian sensation Ivo Van Damme, Rick Wohlhuter (USA) and other talented athletes – Walker had no realistic chance of winning a medal in the 800m, and missing the final gave him a chance to rest and to focus on the 1500m.

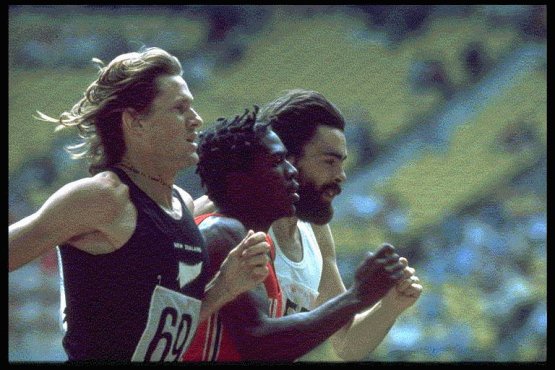

The 1500m final took place on July 31st, and Walker toed the line with future world champion Eamonn Coghlan (IRE), future world record-holder Dave Moorcroft (GBR), the 800m silver medallist in Montreal, Van Damme (who was tragically killed in a car accident later that year), 800m bronze medallist Wohlhuter, ’72 finalist Paul-Heinz Wellman (FRG) and the then Australian national record-holder Graham ‘Gruffy’ Crouch, among the 9-man field.

Without Bayi, there was no real front-runner in the field, and the pace lagged a little (62.48 at 400m/2.03.15 at 800m), with Moorcroft and then Coghlan leading. Walker was poised and in control, sitting just off the lead. At 1000m, Coghlan led, with Walker on his shoulder, with Van Damme and Crouch making moves towards the front. At 1200m (3.01.23), nobody had made a decisive move and Walker was still on Coghlan’s shoulder, ready to pounce.

Wohlhuter moved up to Walker with 250m to go and Walker responded. He kicked hard into the lead and began to stretch the field. Van Damme and Coghlan were caught off guard by Walker and lost a couple of metres to the New Zealander. Walker maintained the pressure around the final bend, held his lead and turned into the straight with a good metre or two on his pursuers. There were late challenges by Van Damme, Coghlan and Wellman, but Walker held on for gold, edging out Van Damme, Wellman and a bitterly disappointed Coghlan, who would also finish 4th in the Olympic 5000m, 4 years later.

Walker’s winning time was 3.39.17, with Van Damme a tenth of a second behind. Wellman ran 3.39.33 for third. Walker covered the final lap in about 52.4 and the last 200m in around 25.3. Crouch finished 8th in 3.41.80, but had done well to make the final, considering that athletes the calibre of Thomas Wessinghage (FRG) and Steve Ovett were run out in the semis.

Walker had emulated his celebrated countrymen, Peter Snell (1964) and Jack Lovelock (1936) in winning what is arguably the most prestigious event on the Olympic track program.

- The First Sub-3.50 Mile – Goteborg, Sweden, August 1975:

On the 12th of August 1975, John Walker broke one of the most significant barriers in middle-distance running, when he smashed Filbert Bayi’s world mile record and broke 3.50 for the first time.

Bayi had snuck inside American Jim Ryun’s world record earlier in 1975 by just a tenth of a second, when he ran 3.51.0 In Jamaica and he effectively threw down the gauntlet to the big Kiwi.

Walker was up to the challenge, as he was in superb form all year. In March of ’75, he’d led New Zealand to a team gold medal in the World Cross Country Championships in Rabat, finishing 4th, just behind American marathon champion Bill Rodgers. Scot Ian Stewart edged out Spaniard Mariano Haro for gold.

Touring Europe with great mate and training partner, Olympic medallist Rod Dixon, it was a stellar northern-hemisphere summer season for Walker. He had run some fast 800m races and he beat a great field to win the mile in Stockholm in 3.52.2. He had also marginally improved upon his national 1500m record a couple of weeks before Goteborg, winning in Oslo in 3.32.4 – the then second-fastest in history.

Walker was clearly primed for something special. The race in Goteborg was held in near-perfect conditions, and the pace was solid from the gun. Australians Ken Hall and Graham ‘Gruffy’ Crouch were there also and Hall was helping out with the pacing. Walker and Hall passed the half mile in 1.55.5 and the three-quarter mile in 2.53.0, when Walker took over and began his strike for home, drawing away from Hall. He was on target for the record with 200m left and he began his final big push towards the finish. He tied up slightly, but held his speed well to the line.

He stopped the clock with the history-making time of 3.49.4, breaking Bayi’s record by over one-and-a-half seconds. Track and field experts regarded this first sub-3.50 mile as a significant achievement, perhaps as important at Roger Bannister’s first ever sub-4 minute mile 21 years earlier.

Walker was feted around the world for his phenomenal run, though in those days, the financial rewards for such a performance were underwhelming. On top of his expenses, Walker said that he received the equivalent of NZ$500 for breaking the record.

Hall was rewarded with a big PB of 3.55.2 in second and Crouch was third. This race cemented Walker’s place as one of the sport’s most outstanding performers. This phenomenal performance set him up as a huge favourite for the Montreal Olympic Games the following year.

- World 2000m Record – Oslo, Norway, June 1976:

Walker targeted the world record in the rarely-contested 2000m distance on the 30th of June as the final big race in his preparation for the Montreal Olympics. Walker felt that the long-standing record of Michel Jazy (4.56.2) was well within his capacity and he planned to take a significant chunk from the Frenchman’s record.

Aided by some superb pacing by Thomas Wessinghage, Walker ran a controlled, evenly-paced race early on. Wessinghage towed Walker through 800m in 1.58.5 and 1200m in 2.56.0, before pulling out. Walker took on the pace, passing 1500m in 3.39.0 and the mile in 3.55.5. Though tiring slightly in the final lap, Walker lifted and ran the last 200m all out. He finished in an astonishing 4.51.52 and he had broken the world record by almost 5 seconds.

The record lasted for 9 years, before British World Champion Steve Cram just dipped under the record, running 4.51.39 in Budapest in 1985. It was a season in which the superstar Cram also broke the 1500m and mile records. Walker’s 2000m time survived as an Oceanian record for almost 30 years, until Australian Craig ‘Buster’ Mottram broke it in Melbourne, prior to the 2006 Commonwealth Games, running 4.50.76. Walker himself rates his 2000m world record as his greatest performance.

- Commonwealth Games 1500m – Christchurch, New Zealand, February 1974:

This race still holds up as one of the greatest championship 1500m races ever run. Walker didn’t win, but ran brilliantly to gain silver. Walker’s conqueror, Filbert Bayi was, at just 20, already an elite athlete, having beaten world-class athletes from all over the world in very fast times. A natural front runner, he would often dominate races from the opening lap, going out hard and holding his lead all the way to the finish.

Walker, 22 at the time, was primarily an 800m runner. Prior to the Games, he had only run 3.38 for 1500m. He was clearly in great form though, as he had won bronze in the 800m at the Games in 1.44.92 – a career-best – with Bayi fourth in a PB of 1.45.32.

With some outstanding Kiwi athletes entered in the distance events and performing incredibly – Richard Tayler (gold in the 10,000m), 41 year-old marathon silver medallist Jack Foster, Sue Haden (800m silver), Rod Dixon and Walker – the expectations were high from the local fans. Walker and Dixon, of course, delivered – though not quite as well as local fans may have hoped.

The 1500m field was stacked with talent. The other finalists joining Walker, Bayi and Dixon were the gold and silver medallists in the 5000m, Ben Jipcho (KEN) and Brendan Foster (ENG) (Jipcho also won the steeplechase), Mike Boit (KEN), Bayi’s countryman Suleiman Nyambui, and three very good Aussies (Graham ‘Gruffy’ Crouch, Dave Fitzsimons and Randall Markey). There was a sense of anticipation in the air, as the knowledgeable observers in the crowd realized that this race would be the highlight of the Games and that Jim Ryun’s seven year-old record of 3.33.1 could be shattered.

As expected, Bayi went out hard and had already opened a gap of more than 10m on the field when he passed 400m in around 54.7. Walker was content to hang back in the pack, and he passed 400m in around 57. Bayi carried on and increased his lead, passing 800m in approximately 1.52.0 – 3 min 30 second pace. Bayi slowed slightly in the third lap (59.5), as the fast first couple of laps took their toll. The chasing group, led by Dixon, could see, as they approached the final lap, that Bayi wasn’t slowing down as much as expected, and they began to accelerate, slowly eating into Bayi’s huge lead.

Sensing the pack was closing in, Bayi began his final sprint with about 250m to go and he held a 5 metre gap going into the last turn, as Jipcho, Dixon, Walker and Crouch were now desperately trying to get to Bayi. Walker moved past Dixon and Jipcho around the last bend and began to close on Bayi, and Bayi rallied. Walker tied up a little after his incredible last lap effort and crossed the line just 2 metres behind Bayi.

Bayi ran a world record of 3.32.16 and Walker ran an Oceanian record of 3.32.52 in second. Both men smashed Ryun’s record. Ben Jipcho ran a Kenyan record of 3.33.16 in third, Rod Dixon ran a PB of 3.33.89 for fourth and Graham Crouch broke Herb Elliott’s 14 year-old national record, finishing fifth in 3.34.22. Bayi’s reign as world record-holder lasted 5 years, before rising British star Sebastian Coe beat the record by 0.13 in Zurich in 1979.

This is the race that catapulted both Bayi and Walker to international superstardom. Walker came away from the race slightly disappointed, but he realized that he had found his calling as a 1500m/mile runner and that he could be the best in the world. This was, without doubt, the pivotal moment in his career.

- 100th Sub-4-Minute Mile – Auckland, New Zealand, February 1985:

Walker ran 135 sub-4-minute miles over his career, and he brought up the ton in a specially-arranged race in Auckland in February 1985. It had been a goal of Walker’s to run 100 sub-4 minute miles for a few years. He had, despite considerable time off due to injury, accumulated quite a number of fast mile times over the years. Walker, now 33, had continued to maintain a consistently high level of performance and he knew it was only a matter of time before he ran his 100th sub-4-minute mile.

Hot on his heels was his close friend and rival, the American record-holder and World Championship medallist Steve Scott. Scott’s sub-4 tally was only about half-a-dozen shy of Walker’s and he was determined to at least try to beat Walker to 100. Scott ran a number of sub-4s early in ’85 and edged closer, though Walker kept his nose in front.

The big day arrived finally. Walker had run his 99th sub-4 in Wanganui on the 13th of February and there was a buzz in the air at Auckland’s Mt Smart Stadium on the 17th of February as Walker attempted to make history. There was a good field, with Irishman Ray Flynn, local talent such at Tony Rogers, Kerry Rodger, Peter Renner, John Bowden (pacemaker) and Michael Gilchrist. Australians Pat Scammell and Peter Bourke were there too – Bourke as a pacemaker.

Walker settled in at the back of the pack, as they went through the first quarter in 57.5 and 1.59 for the half mile. As Bourke took on the pace from Bowden in the third lap, Walker was slowly picking his way through the field and was in position to strike at the bell, with a sub-4 well within range. Walker, challenged by both Rogers and Scammell in the back straight, took control and kicked hard over the last 200m. He opened a 5 metre gap and held it to the line. He won in 3.54.57 in front of an adoring crowd, many of whom poured onto the track after Walker crossed the line. It was another historic moment for Walker.

Scott later claimed that there was an agreement between he and Walker that they would both get to 99 sub-4s, stop running mile races, and then race each other. Whoever won and broke 4 minutes would be the first to claim 100 sub-4 minute miles. Walker denied such agreement existed, and he expressed annoyance at Scott’s comments, though the two men remain close to this day. Walker’s 135 sub-4 minute miles are testament to his incredible resilience and talent.

World Indoor 1500m Record – Long Beach CA, USA January 1979:

It was tough to leave a world record off the top-5 list, but Sir John’s world indoor 1500m record just missed the cut. In 1979, when Walker ran his record at the Muhammad Ali Meeting in Long Beach, the 1500m was not of the program of many meetings in the US – the mile was the main attraction on the indoor circuit. The Wanamaker Mile at Madison Square Garden, the mile races at the Vitalis Meeting in New Jersey and the San Diego meeting were featured races in the US every winter season. Europe’s major indoor meetings were fairly low-key and there was no World Indoor Championship until 1987, so most top athletes focused on the major outdoor meetings of the European summer and tailored their training accordingly, so most athletes were not in peak form in the northern hemisphere winter.

Walker was coming back to peak form in early 1979, after a disastrous 12 months where he missed an entire European season through injury. On the 6th of January, he took on some great athletes in Long Beach and ran brilliantly. Pat Cummings ran aggressively from the front, attempting to shake off his more fancied rivals. Walker eventually got the better of the determined Cummings, holding him off in a closely -fought finish, with top athletes like Sydney Maree, Ray Flynn and Marty Liquori not far behind. Walker’s time was 3.37.4, which took 0.4 off German Harald Norpoth’s record. It was quite an impressive comeback from Walker and another great career highlight.

National Mile Record – Oslo, Norway July 1982:

This was another of Walker’s finest performances. Though British stars Coe and Ovett were hit with serious injury and illness in 1982, their 21 year-old compatriot Steve Cram was emerging as a major force in the sport, with dominant performances in major races, and a resurgent Dave Moorcroft (who had suffered similar injury problems to Walker) was tearing up the tracks of Europe, running a world 5000m record and some other huge PBs. Steve Scott too was in the form of his career, with many consistently great performances over the European season. With other athletes like American Sydney Maree and Irishman Ray Flynn also in great form, Walker was no longer seen as a major threat in international competition and was seen as being on the downward slope of a great career.

However, Walker had overcome injuries with surgery and extensive rehab, and, at the age of 30, was back at his brilliant best. He had run well during the New Zealand summer and arrived in Europe in top form. He had run a near-PB behind Scott, Maree & Moorcroft 11 days before in Oslo and, on a near-perfect night back in Oslo on the 7th of July, Walker was part of one of the great mile races of the era.

Walker was up against Scott, Flynn, just two of the leading athletes in a very good field. Walker went out hard from the gun, tracking the pacemaker through the half-mile in about 1.53. Walker pushed on hard after aout 1000m and led into the final lap. With 250m to go, Scott struck for home and was followed by Flynn. Scott was flying down the home straight and ran 3.47.69, within 0.36 of Coe’s world record. Behind him, Walker rallied and passed a fading Flynn, driving hard to the line. Walker ran 3.49.08 in second, beating his former world record time by 0.32. It was a wonderful performance. Flynn also ran a national record (3.49.77) in third. Walker’s time is still, despite the best efforts of Nick Willis, a national record almost 4 decades later. It remained an Oceanian record for 23 years, until Craig Mottram scraped under Walker’s time by just 0.1 in 2005 on the same track.

World Cup 1500m Silver, Rome, September 1981:

While not quite back to his best, Walker showed at the 1981 World Cup, that he was still capable of great performances. He had missed the previous year’s Moscow Olympics because of New Zealand’s boycott, and Walker, understandably still angry about being prevented from defending his title, was determined to show he was still a major player in the sport.

Representing Oceania, he was up against a top field. Steve Ovett (representing Europe) was in the form of his career and was a clear favourite. There was also Sydney Maree (USA), ageless Kenyan star, Mike Boit (Africa) and European 800m champion, Olaf Beyer (GDR).

The race panned out as expected, with Ovett following Maree and Boit, kicking hard around the final bend and cruising to victory. Walker ran all out down the final straight, passing Boit and Maree and he just nabbed Beyer on the line. Ovett won his second World Cup title in 3.34.95, with Walker second in 3.35.49. It was a great confidence-builder for Walker, who would go on to run some of his best ever performances over the next few seasons.

Late Career:

Walker continued to perform at a world-class level well into his 30s. He ran a sub-3.50 mile at 32 and won the Rome Grand Prix 1500m at 35. He was not as successful with his move to the 5000m. He ran 8th in the 1984 Olympics and he ran a personal best of 13.19.28 in 1986 at 34.

He was still competitive in international races into the late ‘80s and, in 1990, the 38-year-old had the opportunity to run another championship event at home when he competed at the Auckland Commonwealth Games in the 800m and 1500m. He was run out in the 800m semis and, in the 1500m final, he was tripped and fell at the 600m mark. He got up and continued, but finished last in 3.53.77. An angry and disappointed Walker pointed the finger of blame at Pat Scammell, though Walker had no real chance of challenging Englishman Peter Elliott – who was in the form of his career and absolutely dominated the race. Walker ran the European circuit later in the year and ran a 3.55.19 mile in Portsmouth UK.

Walker set his sights on the last big challenge of his career: An attempt to be the first man over 40 to break 4 minutes for the mile. He had suffered some injuries, but by late 1991, he was training hard, running 145km per week and gearing up for an attempt on the 4 minute mile in early ’92, when he would turn 40. Unfortunately, Walker succumbed to an achilles injury while training, and had to abandon his goal. Great rival, ‘Chairman of the Boards’ Eamonn Coghlan became the first 40 year-old to break 4 minutes, when he ran 3.58.15 indoors in 1994.

Post Career:

After running, Walker focused on his horses. Sir John and his wife Helen had trained a number of successful horses over the years, and they ran a small farm with a number of different animals. They also opened an equestrian shop in Auckland, which became a thriving enterprise. He also had a budding career as a TV commentator and worked with Bruce McAvaney for Channel Seven at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992.

In 1996, Walker announced that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. He has taken this life-changing news with incredible equanimity, typical of his attitude to athletics and life in general; he just carried on and has not let it hold him back. He has raised four children with Helen and continued to raise horses and run the equestrian shop. He was elected to Manukau Council for three terms and was later a councillor with the merged Auckland Council, until stepping down in 2019. The demands on Walker were becoming too much, given the stress of dealing with his condition.

Walker’s Legacy:

John Walker is part of a rich history of New Zealand distance running, a tradition that has been carried on over in recent years by the likes of Nick Willis, Kim Smith and the Robertsons, who have no doubt been inspired by previous generations of athletes such as Lovelock, Halberg, Baillie, Magee, Snell, Davies, Roe, Moller, Audain, Quax and Dixon. Rugby still holds the number one spot with Kiwi sports fans, but distance running is a sport in which New Zealanders have punched above their weight for generations.

Much of this has been due to the influence of New Zealand coaching guru, Arthur Lydiard (1917-2004), probably the most well-respected and innovative coach in distance running history. He influenced coaches all over the world, including a number of well-regarded coaches in his homeland.

Walker’s coach, fellow Kiwi Arch Jelley, was a Lydiard disciple, and he also guided other top athletes like Dick Quax, Rod Dixon and Steve Scott. Walker has, of course, had plenty of support over the years from his parents, Helen and his extended family, training partners like Dixon, Scott and Alan Bunce, but regards the now 99-year-old Jelley and the biggest influence on his career. Walker met Jelley as a raw, talented 19-year-old and Jelley molded Walker into the polished, professional, world-class athlete he became. A journalist once asked Walker “What’s the most significant factor in your success?”. Walker replied simply “Arch Jelley”. The journalist went to every single pharmacy he could find, asking for a foot gel, cream or balm with that name. It was only when seeing an interview with Walker talking about his coach that the scribe finally twigged to what (or rather who) Walker was talking about.

Prior to the spectacular successes of Coe, Ovett, Cram and Moroccan Said Aouita in the 1980s, it was due to athletes like Walker, Bayi and Coghlan, that the mile was such a popular event in the ‘70s. It was also athletes like Walker, Scott, Ovett and Cram who helped popularise the big city street miles that began with the 5th Avenue Mile in New York and spread to Queen St, Auckland, The Arc de Triomphe in Paris and Bourke St, Melbourne, among other cities in the ‘80s. George St, Sydney also had an international mile race in the early ‘90s. These events brought middle-distance running to a wider public and they have been a great promotion for the sport.

The athletes of today owe an enormous debt to athletes like Walker, who struggled against the strict amateur codes which still existed in the ‘70s, which prevented athletes earning a living from the sport, despite bringing big crowds and widespread television coverage to events. At the beginning of his career, Walker would work 55 hours a week in a quarry, while running 145km a week in training, building up for the European season. Walker would be a huge drawcard for fans in Europe, and some stadia were routinely filled with 20-30,000 fans, many there to see athletes like Walker and Ovett, and, by the early-80s, sponsors began to invest big money in the sport. With the aid of promoters like the controversial Andy Norman in the UK and Arne Haukvik in Norway, athletics became hugely popular and athletes began to receive lucrative shoe sponsorships and cash prize money by the mid-80s with the advent of the European Grand Prix series.

A few years ago there was a statue of Walker erected in Auckland, which commemorates his win in Montreal – a fitting tribute to a New Zealand icon. How good was Walker by today’s standards? It is testament to his extraordinary ability, that he still owns three national records (1000m, mile and 2000m), the oldest of which – the 2000m – has survived 45 years. Knighted in 2009, Sir John is still revered in his homeland and his outstanding achievements are remembered by athletics fans all over the world. Happy birthday, Sir John.

The author would like to acknowledge The New Zealand Herald, Runners’ World (US), The LA Times, Athletics Weekly (UK), The Great Distance Runners website, The LA Times and YouTube.