RT: Tom, good to have you back on RT. How is the running going?

TDC: Thanks for having me, always a pleasure. Running is going well thanks, taking the foot off the pedal a bit since World Half Marathon Champs in March but looking to gear up for a marathon early 2019.

RT: For the last 40 years the majority of runners have been cruising around in 10m drop shoes (Ed: drop or pitch is the difference in height between the heel and the forefoot of the shoe). Prior to that runners wore very low drop shoes, think Deeks, Derek Clayton etc. Is there scientific basis behind this change to 10mm drops, bigger heel cushioning etc?

TDC: I’d be confident in saying there was no solid science behind the move to more cushioning under the heel and higher drops. Probably more just plausible theory on how running shoes could be better for running on hard surfaces as well as anecdotal evidence from feedback from runners. Since the early days, running shoe companies have been taking input on their design features in running shoes from the feedback of runners in the development and testing stages, before a particular model is mass produced. I’ve heard on the grape vine that some running shoe companies found through internal testing that most runners preferred to run in a shoe with a drop of around 10mm because it was more comfortable.

As recent as early 2018 we can see examples of major shoe companies experimenting with the drop of their running shoe models. Through following Nike’s footwear innovation with their latest marathon racing flat – the Vapourfly 4%, I heard the drop of the shoe was tinkered with during testing quite dramatically. The initial concept shoe actually had no heel – with the idea that it would strip back weight and get the athletes running fast like a track runner over the full marathon distance. As is played out, the runners they had testing the early iterations of the shoe hated it. They found it uncomfortable to run with no heel cushioning and they simply asked for more. The final product for the Nike elite runners like Eliud Kipchoge was custom so we don’t know what the exact drop was, but from the external appearance they look similar to the commercial version, which has a whopping 39mm of heel cushioning and a 10mm drop.

I reckon Deeks and many others in his era wore models with a decent drop too. In his 1984 book ‘de Castella On Running’ there’s a section on drop and this puts in context why they thought a bigger drop was better back then – “a good heel elevation is required to prevent undue stress on the calf muscles and the Achilles tendons, and should be 1.5 – 2cm.”

In the end, there’s no consensus on what is an ideal drop, but no doubt it’s person and task specific. What I see clinically is a higher drop being a little more protective for foot, ankle and lower leg injuries but not necessarily helpful for knee or more proximal running injuries. In fact, a higher drop may have the potential to increase loads on the knee, especially if the tendency for that runner is to overstride a little more than they would with lower drop or less cushion at the heel.

RT: I remember in 2009, all the shoe companies were hitting us hard with their marketing for barefoot type shoes. The end result, some runners fell in love, others got injured, Vibram ended up in court. Was this this an issue with the shoes and therefore the theory behind it, or a problem with the fact that most runners didn’t transition gradually enough?

TDC: Yeah it did get a lot of traction there for a while! In the end, the minimalist shoes didn’t live up to the hype – they didn’t magically make us all stronger, less injury prone or more efficient runners. They worked for some, but didn’t work for many. I see it like this, Barefoot and barefoot mimicking shoes like Vibram 5 fingers are at one end of the spectrum, and a built up highly cushioned motion control shoe like the Brooks Beast is at the other end. Most runners will do best to find something on the spectrum between these two extremes that works for them. I do believe that when it comes to running shoes, a lot of the time ‘less is more’, specifically in the context of weight – if we can strip back some weight with better materials and manufacturing processes without sacrificing something like cushioning, then we’re onto something good. Shoe types, or categories of shoes, are not mutually exclusive – it’s plausible (it has been done by many runners for many years) to wear more cushioned or supportive shoes for some runs, and more minimal or less cushioned shoes for other runs during a training week. The main issue I found was that the ‘barefoot movement’ was vilifying traditional cushioned or stability running shoes and was suggesting minimal was the only way to go for all running once you had transitioned to them. The problem was, many just couldn’t get through the transition to full use of this type of shoe no matter how careful they went about it. There was a study on a 10 week transition to the Vibram Five Fingers from ‘standard’ cushioned running shoes which found about half the runners in transition group developed markers for bone stress injury on MRI compared to just one runner in the group that continued to use conventional cushioned footwear.(1) The interesting part of this study, which ultimately worked against Vibram’s claims, was that the study’s 10 week protocol to transition from conventional footwear to the Vibram Five Fingers was the same protocol recommended by the manufacturers of Vibram Five fingers when you purchased their shoes.

It’s kind of funny reading what was written about not only how barefoot will prevent injuries but also that it would make runners faster. Dr Phillip Maffetone is the inventor of the popular MAF method of training and in 2013 wrote a book titled 1:59; in his book he predicts the first sub 2 hour marathon would be run barefoot. I have no doubt some runners conditioned well enough could run a fast marathon barefoot, à la Abebe Bikila who won the 1960 Olympic marathon barefoot through the streets of Rome. However, what many barefoot proponents will neglect to mention about Abebe Bikila, their barefoot hero, is the fact he won his second Olympic marathon 4 years later in Tokyo, 3 minutes faster, in running shoes. The consensus to date on studies looking at barefoot vs cushioned running shoes on running economy is that the advantage of cushioning negate disadvantages of shoe weight. If you believe industry funded studies like the economy study on the Nike Vaporfly 4%,(2) clearly there are significant performance gains to be made through footwear.

RT: A common issue with middle distance and distance runners. They spend all winter building a base and getting super fit wearing mainly their joggers and flats for sessions only. Then come race time, their Achilles and calves tend to flare up after lots of track sessions or races in the lower drop shoes. Is there a way around this problem? If runners trained all year round in a lower drop shoes would this reduce the probability of lower limb injuries come track time or just result in more injuries?

TDC: Good question, I see lots of injuries around the foot and ankle at the transition from winter base to summer track season partly due to a change in footwear. I don’t think someone necessarily needs to be in low drop all year round to be protected from these sorts of issues, a careful transition period should condition most runners to handle the change. You also can’t blame shoes in isolation, the shift in training loads to more speed work, shorter races or shorter intervals also tends to load the calf and Achilles more. The other factor is surface, in Australia we’re blessed but possibly also cursed by the fact we don’t have many synthetic tracks (compared to the USA or UK for example). We do more training on grass tracks which is great for protecting the lower limb from injury but potentially come track season, if we start racing on synthetic or start doing more training on synthetic, injury risk rises. I would suggest being mindful of all these factors, especially for those with a history of calf and Achilles injures as well as foot and ankle bone stress injuries.

It’s safe to say, it’s important to make sure there isn’t too much of a change in shoe characteristics between flats and the spikes that are going to be worn during summer track season in order to allow the body to handle a decent amount of training and racing in spikes. For example, we now have ‘flats’ like the vapourfly 4% which are super cushioned and have a 10mm drop, this is worlds apart from the Nike Streak LT4 for example, which has minimal cushioning and 4mm drop. The Streak LT4 will be much closer to a spike than the 4%, and thus would be a much safer transition. I would suggest that if you use a high drop well cushioned flat in winter, you need to also use some less cushioned and lower drop flats for at least a small part of your winter season as summer track nears so the change to spikes isn’t too extreme. Another strategy I often recommend to runners with a history of issues transitioning to spikes is simply adding heel lifts into their spikes at the start of track season, then wean off them as the calf and Achilles get used to the added loads of running in spikes.

Practical advice would be; adding speed work very gradually and not giving your foot, ankle and calves a ‘double whammy’ of load by adding more speed work and lower drop, less cushioned shoes like spikes or minimal type flats at the same time.

In summary, main things to consider regarding the transition from flats to spikes is the level of cushioning, stability and drop. Spikes generally function like a zero drop or in some cases even negative drop if it’s a middle distance spike with an aggressive forefoot spike plate. There are many ways of achieving a safe transition and it’s usually up to the runner and coach to map that out together and be adaptable in the training loads (amount of speed work) and footwear (how much and when you’re in low drop and minimal cushioned flats or spikes) depending on how the foot, ankle, calf and Achilles are responding.

RT: One of the main arguments of the barefoot or zero drop shoe movement is that elite runners land on their forefoot, however, research shows that this isn’t really correct. At the IAAF 2017 World Championships biomechanical analysis research was undertake by Leeds Beckett University. Their research was quite extensive and is summarised HERE. In summary, their research found that 67% of male marathon runners, and 73% of women, landed on their heels during the 4th lap of the 4-lap marathon course, and that this pattern wasn’t confined to particular countries or finishing places. What do you take from this?

TDC: It’s pretty easy to counter the assertion elite distance runners are all forefoot and mid-foot strikers with the available evidence. The study you mentioned, as well as at least 2 other studies show the majority of elites racing at half marathon distance or above, are heel strikers. I like to explain it like this; if you’re running so slow that you’re essentially at a fast walking pace, heel striking is 100% going to be the most effective foot-strike pattern. However, if your goal is to sprint 100m as fast as you can, forefoot striking is going to be more effective. For any pace in-between, there will be an array of foot-strike patterns, but essentially the faster we run, the more likely we are to land on the forefoot. A study of foot strike patterns of 283 elite level runners competing in a half marathon found 74.9% were rearfoot, 23.7% were midfoot and only 1.4% were forefoot strikers. In an interesting sub-analysis, they found the top 50 runners at the 15km mark of the race were less likely to heel strike, but heel striking was still observed in 62% of these runners.(3)

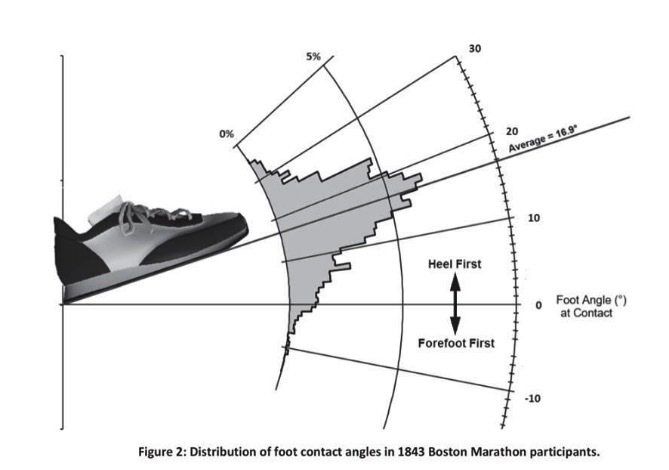

Moving away from just elites, a statistical analysis of 1843 runners at the Boston marathon revealed that 94% of runners were heel strikers.(4) More importantly, it highlighted that fact strike pattern is not as simple as saying you’re a heel striker, mid-foot striker or forefoot striker, there are varying angles of heel contact progressing to a forefoot contact; it’s on a continuum. The researchers measured the contact angles and found there was a bell curve distribution (see graph). Interestingly, the forefoot strikers are 2 standard deviations away from the mean, making them statistical outliers. In my clinical experience, running shoes may increase the angle of heel contact in some runners, but not all. Shoes alone can’t explain the high rates of heel striking in elites and recreational runners. If you look at studies on barefoot populations and how they strike the ground, a widely cited study by Daniel Lieberman, found higher rates of forefoot striking in a group of barefoot Kenyan runners.(5) However, he had them running at speeds of around 3min/km pace – hardly translatable to the vast majority of runners at their self-selected training and racing paces. In a more recent study by a different group of researchers, they found habitually barefoot Kenyans running at more recreational speeds of 5min/km pace were more likely to heel strike – 72% were rearfoot strikers and only 4% were forefoot strikers.(6)

To summarise, foot-strike pattern and touch down angle is runner specific and will be determined by many factors including pace, footwear, running experience and joint range of motion. For the vast majority of distance runners, recreational or elite, a certain angle of heel contact is to be expected as normal and acceptable. If you ever hear anyone say all runners should be landing midfoot or forefoot, please roll your eyes for me. A 2017 review examining ‘optimal’ foot strike pattern states – “We have concluded, based on examining the research literature, that changing to a mid- or forefoot strike does not improve running economy, does not eliminate an impact at the foot-ground contact, and does not reduce the risk of running-related injuries.(7)

RT: The same article reports that when Nike were developing their new racing flat, the Zoom Vaporfly 4%, that they tried to shed the thick heel down in order to save weight, but the elite athletes testing the porotypes hated it, so the heel was put back on. Do you think this is because the high heel has been ingrained into athletes through years of running, or because Nike have nailed it, and this is just the right way to make shoes?

TDC: That’s a tough one to answer! Has to be a bit of both I’d say. The vast majority of running shoes have an elevated heel and this includes toddler and kid’s sizes too, so to some extent we likely adapt to having more under the heel from a young age. When companies like Nike are selling shoes commercially to a mass market, they cater for the average and what may feel best and work best for most, it seems that most are used to, and prefer a little bit of a drop and extra heel cushioning. Thankfully, for runners that don’t want or need so much under the heel and prefer a lower drop, there are more brands doing lower drop options in recent years.

RT: Steve Magness in this article states “The problem is we’ve weakened the Achilles through years of wearing shoes with their elevated heels. Essentially, we’ve created the Achilles problem with the shoes meant to prevent it.”: Do you agree with that?

TDC: Yeah, there’s certainly some merit in it. In most developed countries like Australia, we pretty much start wearing shoes from when we can walk. By the time we’re 2 years old we could already be wearing running shoes that mimic adult footwear with significant heel cushioning and heel to toe drop. Weather this is right or wrong is a topic on its own but nonetheless its happening, so by the time we’re ready for school shoes (again, an elevated heel) we are well used to getting around with more under the heel. It’s very plausible this may set us up for a preference to have running shoes with elevated heel cushioning as adults. It may also mean some level of structural, biomechanical and neuro-motor adaptation will occur as we mature into adults.

However, one way to think about it, for those that hear high drop running shoes weakens your Achilles, is like this; take two people, a runner and a non-runner. The runner runs 60km per week in a pair of Asics Kayano with a 13mm drop, while the other person is relatively inactive but gets around in a pair a pair of ballet flats, vans or converse etc. which are essentially zero drop. Who do you think will have the stronger calf-achilles complex? I would bet on the runner in the Asics Kayano having the ‘stronger’ Achilles because they run; running puts a whopping 6.5-8 x body weight of load through just one of the muscles that makes up the calf-achilles complex. It’s important to remember it’s all relative, even if you run in a shoe with a 10-13mm drop, if you build into the running loads gradually and let the tissues adapt, you can expect a strengthening of the entire musculoskeletal system, including the Achilles tendon.

We need to remember, the drop of a running shoe is probably not a big deal when comparing it to the use of a ‘high heel’– i.e. some women wear a heel to work with a 3cm+ elevation for 8 hours a day for 3-5 days a week. I see the use of this sort of footwear a bigger issue for potential ‘weakening of the achilles’ as well as a host of other issues.

In summary, a higher drop may reduce the relative workload to the Achilles tendon but if we run enough, anyone still has the potential to develop a strong Achilles tendon through their level of physical activity. It’s also very possible to still overload the Achilles tendon with excessive speed work or hill training despite the elevated heel of a 10-13mm drop running shoe.

RT: Obviously some of us require orthotics, others not. Can you provide a run down on the theory behind it and how do semi-elite and aspiring elite runners know if they need to see a podiatrist or not?

TDC: In my opinion, any runner with a foot or ankle injury should ideally seek the advice of a sports podiatrist, especially one that’s experienced in dealing with runners. With extensive anatomical knowledge of the foot and ankle, a sports podiatrist is able to come to an accurate diagnosis as well as identify contributing factors that led to the injury, and recommend a treatment plan that may or may not involve the use of foot orthoses. The modern and progressive sports podiatrist utilises the most effective and evidence based treatments for their runner patients that includes exercises to improve the load capacity of the injured muscle, tendon or fascia, rather than just focus on decreasing the loads via the use of foot orthoses. A foot orthoses should not be used to simply ‘re-align’ the foot or lower limb and they shouldn’t be used just because a runner has a ‘flat foot’. I recommend foot orthoses for many runners as a ‘load management tool’ to help them recover from a particular injury. As such, the use of foot orthoses should be injury specific and be prescribed to reduce the loads to the injured area, without increasing loads elsewhere to their detriment. A foot orthoses can be prefabricated or custom made, and they are certainly not a life sentence for the vast majority of runners. For most, an inexpensive medical grade prefabricated foot orthoses can work extremely well as a short to medium term tool to reduce pain and let the injury heal while we get the area stronger and more resilient via specific exercises or gait modification. With recurring injury, despite careful training load progression and best efforts to increase the strength of the area via targeted exercises, a custom device may be a better option. A custom foot orthoses can cater to more unique foot shapes and abnormal biomechanics, and is generally a much more durable device that can last many years if required.

At the end of the day, you need to see a podiatrist that has a good reputation for treating runners and is neither anti-orthotics (yes they are out there) or overly pro-orthotics to the extent every runner through the door is recommended a set (again, many of them out there). I believe foot orthoses remain an extremely effective treatment option that a podiatrist may recommend to an injured runner when the injury or foot function dictates the potential for benefit. I would recommend seeing a podiatrist that has been recommended by another runner, coach or health professional you trust. In Australia, we are rolling out a certification program for podiatrists to be certified by the national body in ‘sports podiatry’. This is an exciting time for our profession and for the public as it will mean a better experience for the injured runner being able to seek the advice of a local certified sports podiatrist that has undergone further training in this area.

RT: After numerous scientific reviews the ‘American College of Sports Medicine’ came out with a summary of their advice on selecting running shoes. Their advice for what constitutes a ‘good, safe running shoe” is summarised below:

- Shoes with no drop…are the best choice.

- Neutral: The shoe does not contain…extra components (that) interfere with normal foot motion.

- Light in weight

- Be sure the shoe has a wide toe box. You should be able to wiggle your toes easily.

They also advise runners on what shoes to avoid, this is summarised below:

- Shoes that have a high heel cushion and low forefoot cushion (high heel to toe drop)

- Narrow toe boxes do not permit the normal splay, or spread of the foot bones during running. This will prevent your feet from being able to safely distribute the forces during the loading phase of gait.

Thoughts on this?

TDC: These recommendations were published in 2014 – the tail end of a ‘barefoot running boom’ and it’s clear what was on the agenda; rejecting the industry status quo of 10mm heel to toe drop and motion control footwear. To their credit, the available evidence didn’t back up claims that motion control shoes were better for runners who ‘over-pronated’ or that higher drops would protect from injury. A widely cited paper in 2010 showed that the practice of prescribing running shoes based on foot shape didn’t reduce injury rates; the more pronated feet didn’t get less injuries when placed in a motion control shoe.(8) However, rather than base their recommendations on compelling scientific evidence to the contrary (i.e. evidence that minimal type shoes were protective of injury), the authors appear to revert to the appeal to nature fallacy. To date, there is still no evidence that minimal type shoes or shoes void of any support are any better at preventing injury or improving performance. On the contrary, since these recommendations were published there is new data that suggests motion control features can reduce injury risk and those that benefited most from the motion control shoes were runners with a more pronated foot.(9) The same group of researchers found no difference in overall injury rates between 0mm, 6mm and 12mm drop running shoes.(10) There are too many variables that go into what shoe may work best for a particular runner and their unique injury profile for any given distance, pace or terrain.

It’s safe to say we currently can’t make a blanket recommendation one way or the other – not everyone will do well in minimal type footwear and not everyone will do better in stability or motion control shoes. Anyone that tells you barefoot is better, or we should all be wearing minimal type footwear, is not up to date with the latest research and likely stuck in the ‘barefoot running boom’ vacuum.

Two footwear factors I believe could be helpful for all runners is stripping back weight in all shoe categories and having a toe box wide enough to allow unrestricted toe splay in stance and push off.

RT: From the above report by the ‘American College of Sports Medicine’ they state that

“pronation is normal…stopping pronation with materials in the shoes may actually cause foot or knee problems to develop.”

Thoughts?

TDC: Yes, pronation is normal; it’s nothing more than a movement at a rearfoot joint called the subtalar joint. The subtalar joint is an articulation between the Calcaneus (heel bone) and Talus (the bone above) and this joint allows for a unique gliding and rolling movement of the rearfoot that we call pronation and supination. Primarily, pronation allows for shock absorption at the foot level and helps the whole foot to adapt to uneven terrain. Pronation also allows for taking corners or bends at high speeds; if our left foot was not able to pronate as we took a bend on the track, I have no doubt performance would decline and injury risk would increase.

I agree with the authors that ‘stopping’ pronation with materials in the shoe may cause foot or knee problems to develop. However, and this is a big caveat, no running shoe, let alone a foot orthoses can truly ‘stop’ pronation. There have been big question marks over weather a motion control shoe can actually control motion; the evidence is non-systematic and inconclusive. At most, a running shoe with motion control features (such as duel density midsoles) may be able to slow the rate or reduce the amount of pronation in some runners. I still believe that stability features such as, but not limited to, duel density posts can be helpful for injuries where it has the potential to reduce loads to the injured area, such as tibialis posterior tendinopathy.

RT: From the same Steve Magnus article cited earlier, Magness states:

“when racing and training, they (elite runners) generally have higher turnover, minimal ground contact time, and a foot strike that is under their centre of gravity. Since the majority of elites exhibit these same characteristics while racing, it makes sense that this is the optimal way to run fast. So, why are we wearing footwear that is designed to increase ground contact, decrease turnover, and promote footstrike out in front of the centre of gravity?”

Shoes are definitely at least partly to blame for altered running mechanics. However, running shoes were never intended to do those things, it likely became a by-product of the added weight, cushion, drop or stability within the shoe. New manufacturing processes and materials for midsoles and uppers are making them considerably lighter, which I believe is important for facilitating good running form. Having said that, elite runners have always run in ‘heavies’ for training – shoes that are often heavier, more cushioned and possibly higher drop than their faster paced training or racing shoes. With experienced runners, they often self-optimise their stride through years of running. This self-optimisation is aided by speed work, running drills and racing that would generally be done in a lighter shoe. Recreational runners and novice runners I would suggest would also benefit from wearing different shoes for different runs and actively working on good leg turnover which will limit the chance of overstriding in cushioned high drop running shoes.

- Foot Bone Marrow Edema after 10-week Transition to Minimalist Running Shoes. Ridge ST, Johnson AW, Mitchell UH, Hunter I, Robinson E, Rich BS, Brown SD. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013 Feb 22.

- Wouter Hoogkamer et al. Comparison of the Energetic Cost of Running in Marathon Racing Shoes. Sports Medicine April 2018, Volume 48, Issue 4, pp 1009–1019. Open access: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-017-0811-2

- Hasegawa H, Yamauchi T, Kraemer WJ. Foot strike patterns of runners at the 15-km point during an elite-level half marathon. J Strength Cond Res. 2007;21(3):888-893.

- RUNNING BIOMECHANICS: WHAT DID WE MISS? – 35th Conference of the International Society of Biomachanics in Sports, Cologne, Germany, June 14-18, 2017

- Lieberman DE, Vankadesan M, Werbel WA, et al. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature. 2010;463(7280): 531-536.

- Hatala KG, Dingwall HL, Wunderlich RE, Richmond BG. Variation in foot strike patterns during running among habitually barefoot populations. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52548. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052548.

- Joseph Hamill, Allison H.Gruberb. Is changing footstrike pattern beneficial to runners? Journal of Sport and Health Science. Volume 6, Issue 2, June 2017, Pages 146-153. Open access: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2095254617300285

- Knapik JJ, et al. Injury reduction effectiveness of assigning running shoes based on plantar shape in Marine Corps basic training. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Sep;38(9):1759-67. doi: 10.1177/0363546510369548. Epub 2010 Jun 24.

- Malisoux L, Chambon N, Delattre N, et al. Injury risk in runners using standard or motion control shoes: a randomised controlled trial with participant and assessor blinding Br J Sports Med Published Online First: 08 January 2016. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095031. Open access: https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/early/2016/01/08/bjsports-2015-095031

- Malisoux L, et al. Influence of the Heel-to-Toe Drop of Standard Cushioned Running Shoes on Injury Risk in Leisure-Time Runners: A Randomized Controlled Trial With 6-Month Follow-up. August 2016The American Journal of Sports Medicine 44(11) DOI:10.1177/0363546516654690