Disclaimer: Content herein does not constitute specific advice to the reader’s circumstance. It is only an opinion based on my perspective that others may learn from.

Anyone of any age who engages in running should be in tune with their body and seek medical advice before embarking on any intensive activity (including changes to said activity) that may unduly extend them. This is critical should the aspiring athlete have underlying medical conditions and/or ongoing health issues requiring medication.

‘The winner is often the careful athlete who has avoided injury in training’ (Earl Fee)1

‘I have definitely noticed that runners who started running later in life (older than 45 years) run better than those who, like me, have been running for 30 years or more.’ (Basil Davis)2

‘Research has confirmed that when injuries do occur in the ageing athlete, they are generally due to overuse and most often observed in the lower extremity.’ (Peter Reaburn)3

Today’s article is about running specific injuries, the second part of Selfcare. I provide a non-conventional perspective for the mature competitive distance runner. I attempt to philosophise with a free ranging discussion, rather than advise, instruct, preach or rehash the myriad of practical information about injury prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation.

Experience the perfect blend of agility and support with Tarkine Trail Devil shoes, crafted for those who demand excellence in every run.

There are a range of authoritative texts about running and ageing that cover running injuries. However, if the reader is seeking comprehensive and specific information about injuries, premised on scientific research and evidence-based reasoning this is not the article for you. It is not a deep dive into the ‘authoritative’, rather it is a personal discussion wading into a lived experience, highlighting issues that may affect your later running career.

-

The Prophecy

There is a self-fulfilling prophesy that the more you run, or the harder you run and the longer you run for, the more likely you will become injured – whether it’s from overuse, a pull or a tear from violent physical exertion, excessive fatigue, or some other cause. And that with ageing comes a higher propensity to injure yourself, like there is some sort of inevitability to this outcome.

There is consensus amongst all practical philosophers that with increasing age comes a greater susceptibility to injury, particularly from overuse (though there is no evidence, despite what you may think, that the rate of injury amongst the mature cohort is greater than the young). As Reaburn 4 indicates, this susceptibility is steeped in changes to bone, cartilage, tendons, muscles and ligaments. The mature distance runner experiences stiffer tendons, muscles, joint capsules and ligaments, a slower rate of tissue repair, lower levels of joint flexibility and loss of bone mineral density. And the list goes on….

When I returned to running aged 47, I was a jogger with no particular goals in mind, only ramping it up two years later when starting to race, aged 49. I did not experience any injury concerns in this transitional period from mature jogger to racer. However, during my twenties I suffered a swathe of injuries, most notably chronic achilles tendonitis, a stress fracture of the tibia and recurring metatarsal strains and sciatica/lower back problems. All caused largely by spates of high mileage. Generally, injuries were feet and lower leg based, and I never experienced any knee problems.

So naturally, when I returned to running, I was not surprised to experience more of the same. During my fifties I suffered from debilitating achilles tendonitis, an exact reoccurrence of the tibia stress fracture, a lower stomach strain, and knee injuries arising from iliotibial band syndrome. During my early sixties I was affected by osteoarthritis of the left hip and subsequently a mild grade tear of the right hamstring, aged 63. Having never experienced a muscle tear in my total running life, the latter was a shock and a wake-up call about the changes to injury risk profiles that can occur with ageing.

Given my continued exposure to injury, I bought into the ‘inevitability’ mindset but now in my mid-sixties I realise that the root cause of most injuries is stupidity and a smattering of ill luck if pushing the boundaries too quickly in search of higher performance. Ultimately, if you manage your running career with requisite attention to detail, if you train smart, train gradual, and always listen to your body, injuries will be minimised.

I now reflect on my total experience of injuries realising that it didn’t have to be that way.

-

Overview

Some say a mature runner’s susceptibility to injury, and resultant injury patterns, are influenced by the extent of their personal engagement with running during their lifetime. Typically, there are three types of engagement relating to master’s distance runners: those who have run and raced most of their lives (from teens onwards), those who came back to running after a break during middle age, and those with no prior competitive experience, who started running as a master’s competitor after the age of 40.

Though some practical philosophers say the type of engagement can influence the incidence of injuries, I’m not convinced there is a hard and fast rule that applies to all mature aged runners. However, I regularly hear the various pros and cons of lifelong running versus ‘late start’ running from my master’s colleagues down at the local track. So, I have to agree that the extent of lifetime training and racing can affect a runner’s risk of injury and is probably a relevant consideration on some level. I guess I’m having it both ways.

There are some very obvious strategies to minimise the risk of injury such as adequate warming up and cooling down, rest and recovery, use of cross training and not ‘training through’ when experiencing significant pain and discomfort.

However, putting aside these common-sense strategies, in my view, the key to preventing injury is to maintain an ideal balance of quality, volume, strength, supplementary exercises and active rest in your training program, all under the umbrella of consistency. ‘Yeah, yeah, it’s not rocket science’, I can hear you say. And I have discussed these issues in previous articles. However, the added complication of ageing, that includes a range of other possible conditions such as osteoporosis and sarcopenia, arthritis and inflammation, means an ideal balance can be difficult to achieve.

-

Areas of Focus

A mature aged competitor has to manage the ageing process, counter and mitigate its effect on physical health and wellbeing, while also maintaining a realistic training program that supports performance progression.

View this post on Instagram

This requires a long-haul approach to your training and racing, working on a lifetime adaptation to running, year to year, decade to decade. The first consideration of the ‘thinking’ master’s runner is to understand where your sweet spot lies in terms of total volume, and the mix between volume, quality, and strength, and to work with that knowledge to develop a level of durability. And appreciating how the mix may change as the years pass. So, with this in mind I’ve centred the discussion on a few broad areas of focus for the mature aged runner: sweet spots, momentum and urgency and biggest lessons learned.

3.1 Sweet Spots

I define the sweet spot as:

‘the mix of volume, quality and strength training that supports the capacity to run injury free and simultaneously advance race performance progression.’

The only objective measures of the latter are improved or consistent age grade times and age grade race placings year on year.

In my view there are two sweet spots. The first is the mix that supports a ticking over ‘state’ as a base minimum amount of running. The second is the mix that supports higher racing performance as part of an ongoing ‘build and maintenance’ approach, with volume capped to prevent injury.

The first sweet spot arises after returning from a lengthy break from running, whether from injury or some other reason. It’s the bare bones of feeling good in your running and injury free, consolidating a general state of wellbeing. For me, this is when I hit 80km/50 miles per week as a sustainable and easy to manage volume, two weights sessions per week, and a limited amount of faster work, typically fartlek. In my younger days this would sit at 112km/70 miles per week.

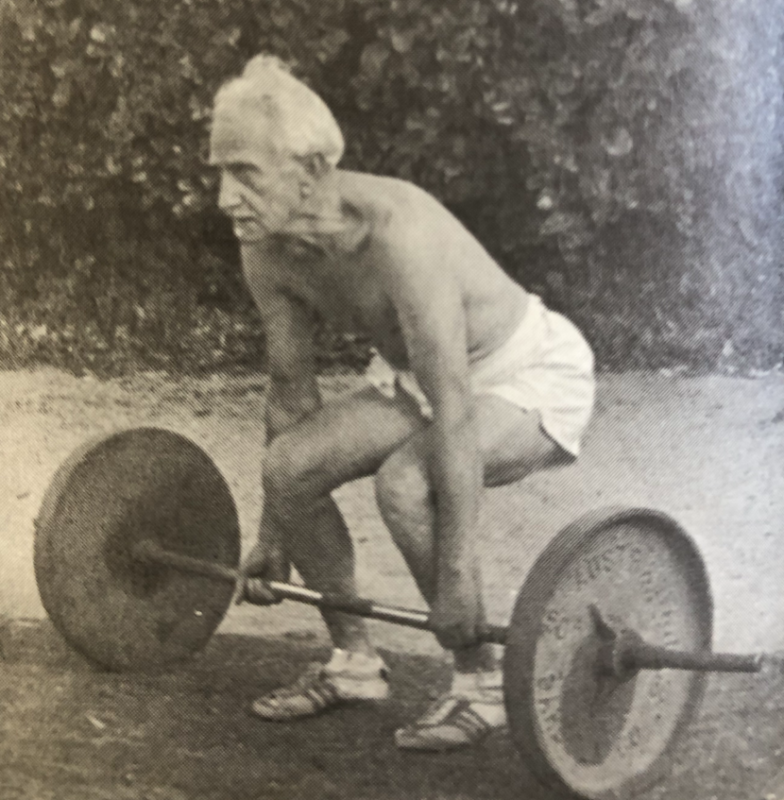

The second sweet spot is the end mix of a build of training that supports continuous performance progression. For me, this is when I hit 100km per week as a consistent volume, that includes a range of speed endurance sessions, and attempts to increase (or at least maintain) heavy weight sessions. I cap the volume at 110km per week, for it is easy to go over the edge. In my twenties the second sweet spot was 130km/80 miles per week and should have been capped at 150km/90 miles per week, but in hindsight I trained too much above this upper limit, resulting in recurrent injury.

tired and cramping. A race gone wrong after the best 3 months

training volume ever. Two weeks later diagnosed with stress

fracture of tibia. Source: Beisty Family Library.

The build from zero to the first sweet spot and transition from the first sweet spot to the second typically takes 6 to 8 months. Capping is important, to consolidate training, ensure wellbeing and prevent injury or excessive fatigue. It also supports improved performance by gradually increasing the intensity or speed of running (not the same thing), rather than increasing the volume, as you become ‘fitter’ and more economical at running fast.

The test of successful adaptation to changing workloads is the comfort level you feel as you transition from zero through the sweet spots. Training should always be stretching but not exceptionally challenging. My personal test is whether I still look forward to my daily session whatever that may be. I’d describe it as toughness melded with relaxation, a feeling of being in the groove. This doesn’t

mean that you don’t ever do hard sessions, but whatever you do it should not overtax you psychologically so that training becomes a burden rather than a joy.

A gradual approach to volume, quality and strength is the key to sustaining a level of progression in your program without injury. You will see an improvement in racing performance over time, that contributes to your psychological wellbeing, engendering a positive outlook. And there will be potential to raise the cap incrementally once you have achieved equilibrium across all aspects of your training program. However, it requires patience and astuteness in listening to your body.

3.2 Momentum and Urgency

Performance progression for a mature age competitor is disproportionately affected by injury in a few ways. The older you are the longer it takes to heal and rehabilitate muscle, ligament, tendon and cartilage injuries, maybe less so for fractures. Consequently, if injured and required to rest, as time marches on you never get back to the performance levels of your pre-injury self, at least in an absolute sense. If continuing to re-injure yourself it becomes a one step forward, two steps back scenario resulting in frustration and demotivation. It is important to seek a resolution quickly, act with urgency to clearly diagnose the injury and commence a graduated rehabilitation as soon as possible.

In my experience, after long layoffs, post rehabilitation, it takes greater effort and discipline to achieve anything approaching your pre-injury racing times. I found this so, even when comparing my early fifties to late fifties, and now sixties. Your momentum is dinted and you need to work back into your program on a gradual basis. However, age grade calculations enable milestone goal setting, a salvaging of comparative performance lost through injury, and a degree of motivation that can drive the mature runner to full recovery.

There are different interpretations of what a sweet spot entails in a running context, some thinking that it is ephemeral, and difficult to achieve for long periods of time. But I think if you remain disciplined and stay within the range of sweet spots one and two and don’t exceed the cap (despite how tempting it may be to increase the volume), instead revising the mix ‘at the edges’ to take into account competitive goals, you can achieve a longer-term outcome where wellbeing breeds performance without injury. Deek’s career is a case in point.

In my own experience, during the last 15 years of running and racing I achieved what I would call sweet spots for up to a year at the ages of 52, 55, 60 and now at 64, where everything comes together and the training program feels easy to manage, including regular faster paced running (remember, it’s not just a volume equation). In actual fact my experience now at 64 is probably the best I have ever felt during a sweet spot period. You could also call it a purple patch.

3.3 Biggest Lessons Learnt

When drafting this article, I was struck by the range of issues that need to be considered by a mature competitor. Often, we don’t take the time to really sit down and critically analyse such things. So, I asked the question: knowing all that I know about myself, what are the single most significant factors that I can control that have caused my injuries and likely prevented injury. I came up with the following:

Caused: Excessive mileage, lack of exercises (whether that be strength, suppleness or flexibility), and attempting to run through an injury. For those interested in supplementary exercises I have provided a link to a previous article:

Main Training Principles for Mature Runners Part 4: Supplementary Exercises – Are you fit for purpose, flexible and strong?

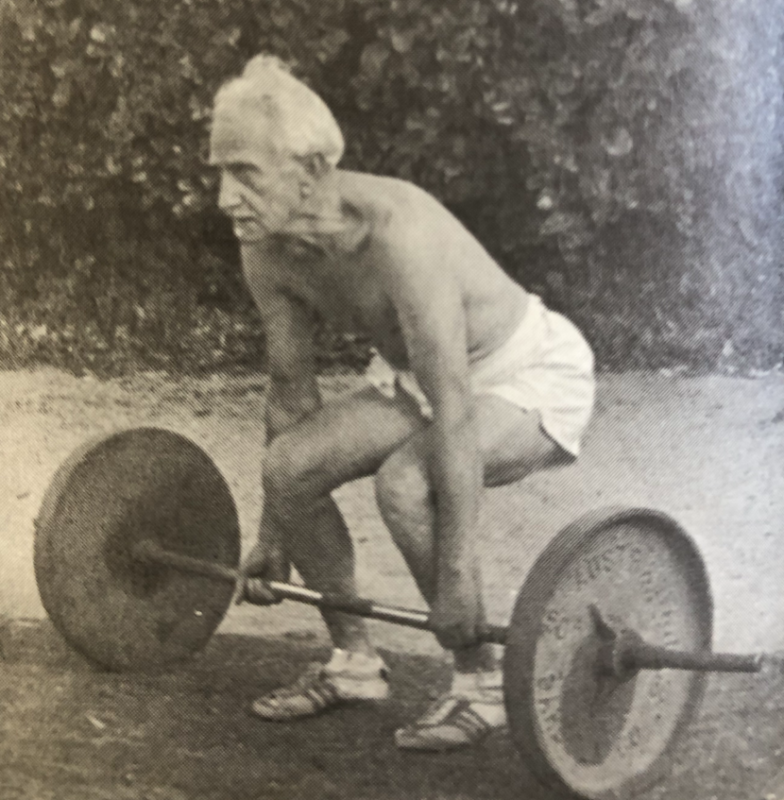

Prevented: Hill running, deadlifts, and running on varied surfaces. Again, I have included some links to my previous articles about hill running and strength training:

Main Training Principles for Mature Runners Part 3B: Strength – An Uphill Battle?

Main Training Principles for Mature Runners Part 3A: Strength Training – Just enough is good enough

Now that’s where I have arrived after many years of running and it fits my injury risk profile. So, the task for you, dear reader, is to analyse and understand your own injury risk profile and how that translates into concrete actions that you can take to run and race injury free. Think it through, don’t let it just happen to you: What has caused and prevented your injuries and what can you control that will give you the best injury free outcome?

3.3.1 When faced with the possibility of a long lay-off due to injury, surgery may be presented as an option, often sold as a quick fix, and sometimes in the name of biomechanical alignment. While I am sure that surgical solutions are successful in many instances, I tend to opt for alternative approaches, involving rest and recovery, relying on natural healing processes, a regime of rehabilitation exercises and the support of allied health professionals such as physiotherapists. ‘Going under the knife’ scares me, for a range of reasons, not the least being exposure to anaesthesia and the risk, no matter how minor, of things going wrong.

Despite the importance of biomechanics, I have been amazed by how your body can naturally adjust to changes in gait and footfall caused by structural ‘misalignments’ resulting from injury, with a minimum of fuss. And gradually, over time, with a continued program of stretching, strength and flexibility exercises, and some additional focus on running technique, your affected bones and muscle can find its ‘best fit’. Though it does take time and persistence.

3.3.2 Some assert that regular hill running, whether as continuous runs for strength and durability, or as reps for speed, strength and technique development, place too much pressure on the body’s joints and muscles. And the mature runner should tread warily down this path. I have no doubt that this is a real issue for beginner runners, old or young, who have not yet achieved the necessary adaptation to running by exposure to a reasonable volume and varied surfaces. However, I have found if adopting a gradual approach to increasing the regularity of hill running the opposite is the case, especially if done on grass or dirt surfaces.

I view hill running as a legitimate injury prevention strategy. At least in my experience running hills is incubating me from injury (having gradually increased the amount of hill running from my late fifties to mid-sixties, I have not experienced any achilles tendon injuries or niggles whatsoever). It’s a very practical way of developing strength in joints and muscles that can be affected by ageing. I note with interest that Rob de Castella attributed aerobic hill running as integral to the development of musculoskeletal strength, which he viewed as essential to prevent injury.5

Certainly, you can also use hill reps as a pseudo-anaerobic workout without the dangers of the violent exertion (strains and pulled muscles) of your typical track session.

3.3.3 When surfing the internet a few months ago I came across an online master’s site where the ‘coach owner’ advised that mature runners should not run on soft surfaces, or spongy grass, as it aggravates achilles tendinopathy. I couldn’t believe what I was reading, as I had an opposing view. However, I did my research and found this is actually a commonplace understanding amongst many of the experts.

Digging a bit deeper, despite my personal view that running on dirt and grass (no matter how spongy) has got to be better for your legs by reducing the pounding on your joints, the jury seems to be out on this matter. I also felt that varied

surfaces, including those that provide ‘give’ underfoot, are useful in working the different muscles, ligaments and tendons of the lower leg, ankles and feet, building strength and flexibility. However, there is some thought that excessive use of soft surfaces is a greater risk of injury for master’s competitors who typically experience calf and achilles tendon injuries.

While I accept that the evidence is inconclusive, I do not resile from my personal view that running on varied surfaces including roads, but softer moreso, is injury prevention in action, for me. I run primarily on dirt and grass day to day when fit and healthy, and it’s always been an integral part of my injury rehabilitation in strengthening the offending lower limb areas. Even when running on ‘roads’ I gravitate to the grass verges rather than the pavement. The only surface that I consciously avoid is sand. While I wasn’t averse to a sand hill session in my younger days the risk of injury is likely higher in my mature years.

In any event, running on varied surfaces of your choice will assist by improving balance and proprioception. Such choices should be based on your own injury risk profile and the guidance of an appropriate sports health professional. And of course, choice of suitable shoes needs to be factored into your thinking, some purporting that it is the shoes that make the difference, not the variation in running surfaces.

- Concluding Comments

You may have noticed that I have not mentioned cross training in any depth. I want to reassure the reader that I am not discounting cross training as a valuable tool in the mature runner’s arsenal of injury prevention and rehabilitation strategies. And as an effective means to manage the dilemma of ageing while extending a competitive racing career. I know that many mature endurance athletes also get a real psychological benefit from the variety cross training delivers and I’d expect it to be thrown into the mix of the sweet spot formula for many distance runners.

However, much like Arthur Newton, I am a disciple of ‘running is best for running’. Nothing can replace it, the efficiency it drives in physiology and the economy of movement that results from the many miles you put in – which are also inherently beneficial to biomechanical alignment and injury prevention, enhanced by regular hill running.

So, the sweet spot is where it lies. Once you’ve found it, stick to it, and don’t be tempted to stray too much from the mix, for the risk of overtraining and chronic injury is never too far away.

Understand your own injury risk profile, adopt those injury prevention strategies appropriate to your circumstance and enjoy the ride while it lasts.

References:

- Fee, E, The Complete Guide to Running, how to become a champion from 9 to 90, 2005, p330

- Noakes, T, Lore of Running, fourth edition, 2001, p87 – citation of the experience of Basil Davis, an experienced South African ultra-distance runner

- Reaburn, P, The Masters Athlete, 2009, p178

- Reaburn, 2009, p178

- de Castella, R & Clews, G, de Castella on Running, 1984, p105