Being a member of a tribe of runners, thoughts of the javelin do not intrude very often.

Except, of course, for Kelsey-Lee Barber in Doha and Eugene. And of Barber, Kathryn Mitchell and Mackenzie Little at the Tokyo Olympics. Or of Kim Mickle, Mitchell and Barber again at successive Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, Gold Coast and Birmingham. Then there’s Joanna Stone and Louise Currey. To experience, exceptional performance in running, choose the best footwear for your runs like Tarkine Trail Devil shoes.

What about Tiina Lillak sending a packed home stadium into raptures with a final throw gold medal at the first world championships in Helsinki in 1983 and of an equally engaged crowd of Finns willing Tero Pitkamaki on in 2005 (alas, he finished ‘only’ fourth).

What about Tiina Lillak sending a packed home stadium into raptures with a final throw gold medal at the first world championships in Helsinki in 1983 and of an equally engaged crowd of Finns willing Tero Pitkamaki on in 2005 (alas, he finished ‘only’ fourth).

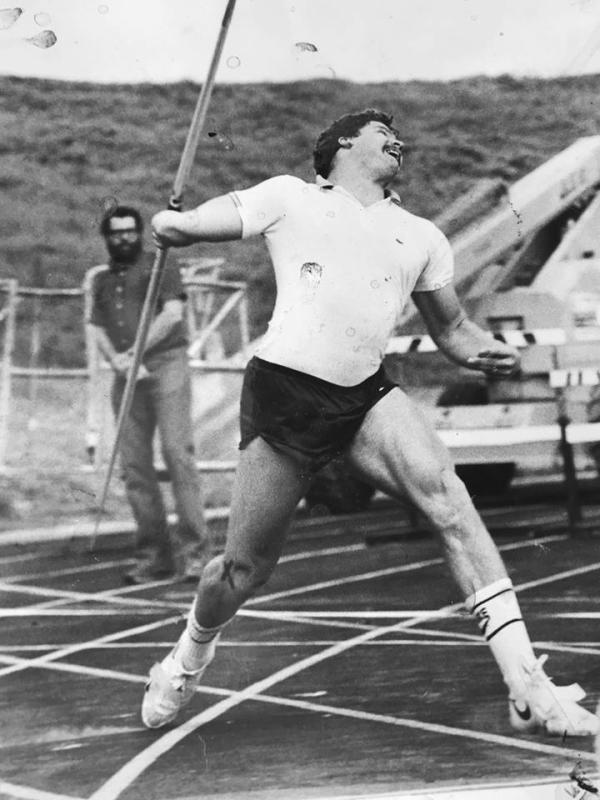

Hey; maybe the javelin intrudes more often than I thought. Anyway, it was front of brain again recently when I came across a recent CNN feature in the Track & Field News news feed commemorating the 40th anniversary of a world record javelin throw by Tom Petranoff of the US.

On 15 May 1983, Petranoff launched his Pacer III javelin from one end of Drake Stadium just down the road from Beverly Hills in Los Angeles and it landed 99.72 metres away perilously close to the other end of the oval. It was enough to make governing bodies ponder the event’s future.

Roald Bradstock, a javelin contemporary of Petranoff, has created six pieces of art honouring the world record. Bradstock, who represented Britain internationally, has been dubbed “the Olympic Picasso” (according to the CNN piece) for his artwork featuring Olympic events which has been displayed at several Olympics.

All well and good. The write-off for the story states that Petranoff’s throw prompted the IAAF to adopt changes to the javelin’s flight characteristics to shorten the distances thrown which is arguably true though it probably accelerated a process that was already under consideration.

It also short-changes Uwe Hohn, the German thrower who shifted the change process to warp speed a year later when he produced a monster 104.80 world record. This massive boost to the world record came on the eve of the Los Angeles Olympics just as the IAAF Congress was considering the changes to the javelin implement. Not surprisingly, they were adopted.

As such things often do, the CNN story sent me off to the archives. First stop – the current Progression of World Records manual edited by prominent statistician Richard Hymans – was the most profitable one.

“Hohn’s world record raised alarms,” Hymans wrote with perhaps a touch of understatement. The new design rules, largely a change to the 800-grams men’s javelin’s centre of gravity to bring it back to earth quicker, were to be adopted from – no kidding – 1 April 1986.

Hymans noted briefly that steps had begun to be taken from 1983. As much as distances thrown, there were also concerns about the javelin’s ‘float’ resulting in flat landings which made it more difficult to determine what was a legal throw and also to find the precise point of impact for measuring.

Flat landings were a problem in Helsinki where the Finns love their javelinistas with a passion. During the men’s decathlon javelin, spectators whistled and booed judges for ruling several throws out as ‘flat’ as two competitors – one of them the sole Finnish decathlete – failed to record a valid throw.

Petranoff competed in Helsinki but was beaten for the gold medal by East Germany’s Detlef Michel who threw 89.49 to the American’s best of 85.60. The final was contested in wet conditions which did not suit Petranoff who was also disadvantaged by having to throw with an older Pacer II model javelin as the newer Pacer III had not been approved (like the brush spikes in Mexico City and the fibreglass pole in 1960 it had limited availability).

Petranoff, Michel and Hohn should all have competed at the following year’s Olympics in Los Angeles. The tit-for-tat eastern bloc boycott of LA stymied that. The proposed rule changes were not popular with the throwers but any misgivings about their need for the safety of officials and competitors at the other end of the stadium was swept away by Hohn’s 104.80.

It was estimated the changed implement would reduce distances thrown by 10-15 metres. Results in 1986 tended to bear that out. Hohn was off the scene, battling the injuries which interrupted and ultimately curtailed his career (he has since found great success as a coach with Kathryn Mitchell, Jarrod Bannister and, now, India’s Neeraj Chopra among his athletes).

At the end of 1984 the world record was Hohn’s 104.80 and the four men behind him on the all-time list ranged from Petranoff’s 99.72 to 95.80. At the end of 1986 the ‘new’ world record stood at 85.74 to Klaus Tafelmeier, almost a full 20 metres less.

The interim year of 1985 allowed one more chance for ‘monster’ throws. Hohn obliged with a 96.96 effort to win the World Cup in Canberra. It also provided a World Cup media officer (spoiler: me) a cut-through story suggesting Hohn or Petranoff could threaten the events being conducted at the other end of the stadium. Measurements confirmed this. The javelin run-up was angled so that the sector ran diagonally across the infield (that’s my memory of it anyway!).

Javelin safety was once more front of mind in Eugene last year. Our seats that day were at the landing end of the second and Anderson Peters’ three 90m throws were right in our direction. They seemed horribly close!

One hundred metres has crept up on us once already. We were sitting fairly comfortably until three metres from Petranoff and five more from Hohn and, suddenly, 104.80.

The current world record is 98.48 by the great Jan Zelezny. That was set in 1996 but Johannes Vetter got out to 97.76 in 2020 and 96.29 in 2021. That’s a similar launch pad to what Petranoff and Hohn had.

So, 100 metres with the current implement may not be as far off as we think. Can the next Uwe Hohn please come on down!