Class act rewarded | A Column By Len Johnson

Cathy Freeman unzipped her body suit and sat down on the track. Sally Pearson let out a scream once her narrow victory had been confirmed.

Nathan Deakes dissolved into tears of joy. Rob de Castella, so injury-proof he was nicknamed ‘The Tree’, was almost lumbered by a laurel wreath. Distinct reactions to different moments of triumph.

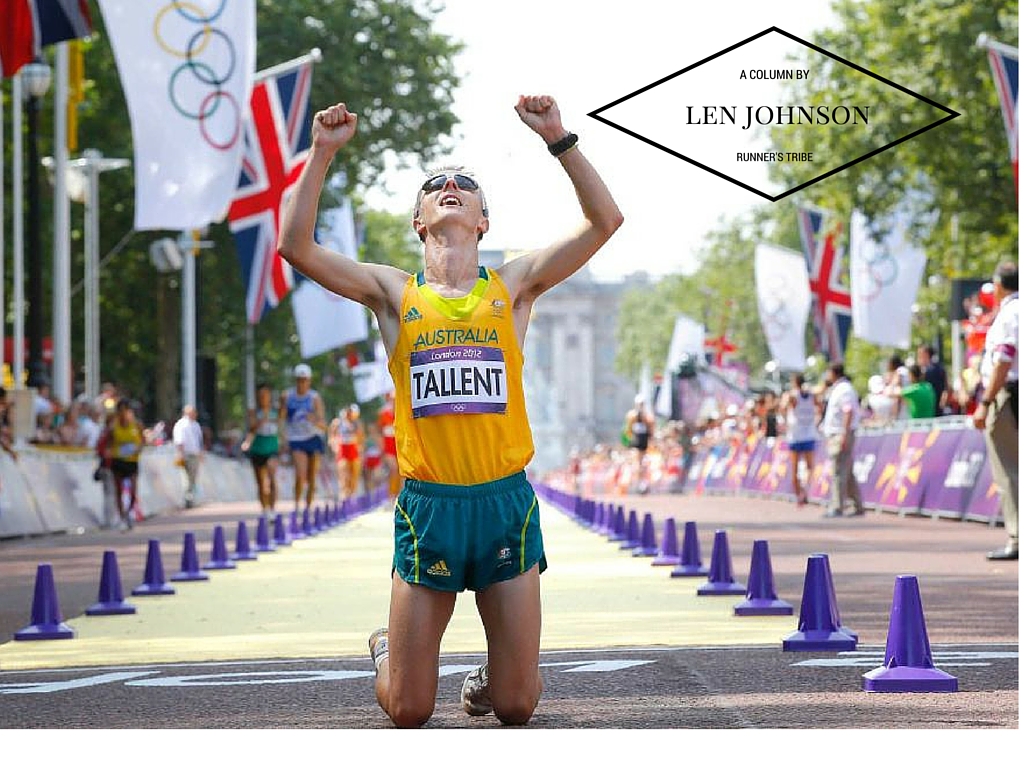

We will never know how Jared Tallent would have reacted to his gold medal at the London 2012 Olympics, because that moment was taken from him. Sergey Kirdyapkin, by dint of a sleight-of-hand judicial process allowing him to split a drug suspension into two parts either side of the Olympics, had crossed the line a minute earlier, leaving the Australian second in the 50km road walk for the second Olympics in a row.

In a long-expected decision, the Court of Arbitration for Sport has ruled in an appeal against the sentence brought by the IAAF that the arrangement which let Kirdyapkin have his PEDs and eat his Olympic cake, too, was an artificial contrivance. Consequently – once some I’s have been dotted and T’s crossed, specifically the ‘i’ at the IOC – Jared Tallent will be the gold medallist.

Tallent will never get back the moment he should have had on 11 August, 2012 on The Mall outside Buckingham Palace. He deserved to be crowned Olympic champion then, rather than have it decided almost four years later that he should have been. His coach, family, friends and teammates will never have the celebration they should have had.

Tallent’s coach, Brent Vallance, deserved to be acclaimed as the coach of an Olympic gold medallist back then, rather than it being just a footnote to today’s bigger story which, naturally, focuses on the athlete. We don’t have so many Olympic or world champions and coaches as to be able to ignore any of them.

When that Irish serial pest tried to bundle Vanderlei de Lima off the Olympic marathon course in Athens in 2004, he not only robbed de Lima of his winning chance, but also diminished the performance of the gold and silver medallists, Stefano Baldini and Meb Keflezighi.

As many marathon experts as you like can say how certain they were that Baldini and ‘Meb’ would have passed the tiring Brazilian, but the incident occurred before either of them actually did. It robbed all three athletes, taking away de Lima’s chance of glory and leaving a query, however slight, on the medals won by other two.

It is the same with the drug-takers. That they rob themselves if detected, either immediately or subsequently, is their own look-out; that they rob their fellow athletes can never be satisfactorily remedied.

Kirdyapkin, Victor Chegin and his whole dodgy school of walkers, and Russia have all had their comeuppance now, but it does not fully restore the glory to Tallent and his team that should rightfully have been theirs on that sunny August morning in London almost four years ago.

One of the most striking things about Jared Tallent’s reaction to all this has been the dignified way he has argued his case. Despite what we now know about Kirdyapkin, the Victor Chegin group and Russian athletics in general, his public commentary has confined itself to the specifics of his case. Kirdyapkin has been the agent of his own demise, sunk by the artificiality of the arrangement that divided a longer sentence into two parts, conveniently split so he could compete in London.

Not so much as a designer drug, as a designer drug sentence.

The London 50km walk is a relatively simple matter. The ‘winner’ should not have been competing, so it is relatively easy to see justice done by elevating Tallent to the gold medal and others accordingly.

There are other races in recent, and more distant, Olympic and world championship history that we also know to have been influenced by the use of performance-enhancing drugs. The Ben Johnson 100 in Seoul in 1988 in which a case can be made that every athlete in the final was doping, or caught up in a doping scandal, at some stage of their career, is the most infamous.

The Sydney 2000 women’s 100 final was won by Marion Jones, who subsequently (2007) admitted doping. Trouble was, the silver medallist, Ekaterini Thanou of Greece, was also by then implicated in a doping case. Eventually, the IOC stripped Jones of her medals, the simple part, then upgraded Tayna Lawrence and Merlene Ottey to silver and bronze, respectively, without disqualifying Thanou. There is officially no gold medallist.

The London women’s 1500 final presents a similar dilemma. Three of the first four across the line – ‘winner’ Asli Alptekin, second-place Gamze Bulut and fourth Tatyana Tomashova – either disqualified or provisionally suspended for doping offences; and two more athletes in the top eight. One of the latter is Abeba Aregawi, fifth across the line, who is provisionally suspended after a positive test for meldonium, which was only added to the WADA list on 1 January. As far as we know, Aregawi was clear on 31 December, 2015, much less four years ago.

It is next to impossible to make sense of that race, with athletes who did not even make the final robbed of medal opportunities. Perhaps ‘no race’ would be the fairest decision.

Sadly, it is not possible to right all wrongs, not even in retrospect. Thankfully, Jared Tallent’s case is not one of those.