A Column By Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

The Wages of Fear is a 1953 movie about four men who are asked to transport a dangerous cargo of nitroglycerine.

The plot of the Franco-Italian, noir-nero drama is simple: four men, broke and stranded in a South American oil town, are contracted to transport the unstable explosive in trucks, to adopt a phrase in current usage, ‘not fit for purpose’.

An unscrupulous oil company – is that an oxymoron – needs the explosive to extinguish an out-of-control fire in one of its wells. The question is, will either truck survive the journey over rough and ready mountain roads before the payload explodes (spoiler alert: the answer is ‘no’, and ‘sort of’).

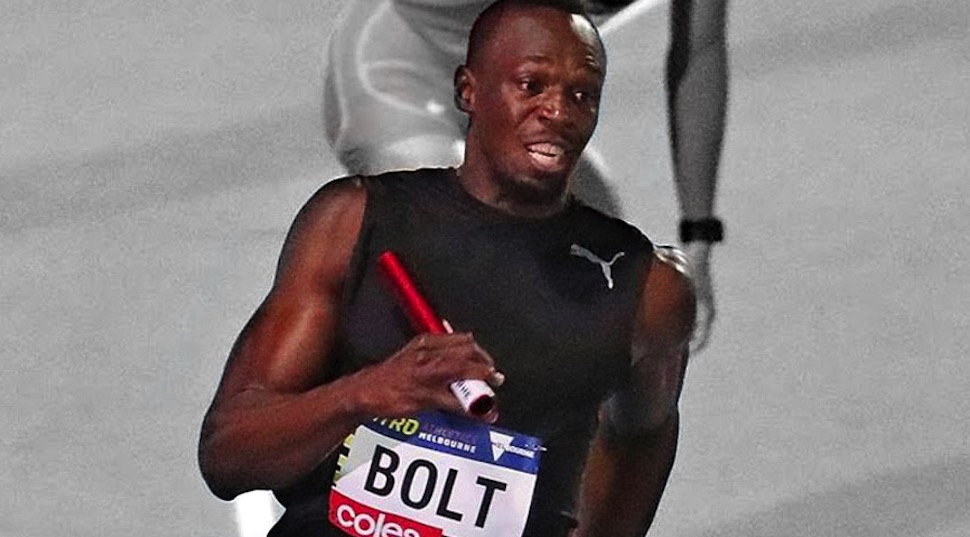

Nitro Athletics had its explosive moment at Lakeside Stadium on Thursday night when the initial awarding of last-place points to the disqualified Australian 4×100 metres relay gave the home team an unexpected victory over the Bolt All-Stars.

Athletically, this was no big deal. This sort of thing happens in major championships all the time. The relay is run; the qualifiers, or medallists, appear to be decided, and some time later comes the announcement that the USA (apologies to our American friends, but it’s always the USA) is disqualified for completing a change outside the zone.

It happened in Rio, the decision coming some 15-20 minutes after the final as the US men’s team was taking its lap of honour alongside Jamaica and Japan.

Fifteen minutes leeway is what you don’t have in Nitro Athletics. One of Nitro’s selling-points is that it moves so fast you’re onto the next thing almost before you’ve had time to fully savour the previous one. Or, in the case of the mixed 4×100 which closed Thursday’s program, you’re wrapping up the night and the fans are streaming out of the stadium.

Nitro also has – and the Olympics, world championships, national titles and even club athletics do not – live post-race interviews while the sweat is still dripping. This was the unstable explosive bouncing around in the back of the truck over dangerous mountain roads on Thursday night.

It was not nitro, nor was it TNT. it was UB that went off with a bang.

Initially the scores went up on the board assuming Australia – by dint of the disqualification – had finished last and would be allotted the 40 points for last place. That gave the home team a 15-point ‘win’ over the All-Stars (who had also received a 100-point bonus because theh had drawn the relay as their power play).

“It doesn’t make sense,” Bolt exploded. “If you get disqualified and you don’t lose any points, it doesn’t make any sense. That doesn’t add up.

“You can’t not lose any points, so I’ve got to talk to the organisers and figure it out, but I’m sure we won the night.”

Turns out Bolt was right. And it is understandable he was in an explosive mood. The change between the incoming Jack Hale and the outgoing Fabrice Lapierre was so far out of the zone it might as well have been in the next suburb. One more step and Lapierre would have been on Middle Park Beach, rather than Lakeside’s blue polyurethane.

Compounding matters, the television picture quite clearly showed Lapierre had stepped inside the lane in his attempts to stay within the exchange zone.

So, there it was. Australia disqualified, the Bolt All-Stars winning for the second night in a row, leaving them in an almost unassailable position coming into Saturday’s third and final night.

You can look at this any number of ways – and most of them have some degree of validity. I prefer to ignore all that, however, and go straight to the overall look for the competition.

Predictably, the initial reports centred on the farcical nature of events. Fair enough: but it would have looked just as farcical in the fast-paced Nitro set-up to have gone the usual protest, result, possible appeal and counter-appeal, final result route. Just as nature abhors a vacuum, so, too, do fast-paced events abhor due process.

But then you couldn’t go the express route either, because Nitro referee Steve Moneghetti is not the actual referee. It looks great on television (could we lose that uniform, though), but the actual referee is a qualified senior official and, in the likely event that he/she did not witness the alleged infringement, has to uphold the ruling of the official (again, the actual qualified official) on the changeover.

This, in turn, is the starting gun on the lengthy process described a little earlier.

The more important thing the relay contretemps illustrates – from the improvised nature of the Australian team to the Bolt blow-up – is that athletes are taking this thing seriously.

There’s been so much emphasis on joy, laughter, banter and crowd interaction that you could be excused for thinking Nitro Athletics was as much a love-in as a genuine contest.

Now, this has great merit, too, no better exemplified than when Theo Campbell, a little known sprinter from Bath, blew Mitchell Morgan a kiss as he blew by in the final strides of the 4×400 metres relay which opened Thursday night’s program. A delightful touch, delivered and accepted with not a hint of over-playing.

But we want to know, too, that athletes want to win this thing. It has occasionally looked that way, particularly with the whole-hearted racing of the Australians (could those competing for Bolt All-Stars just back off a little), with Campbell’s chase-down and with Erin McBride notching up another win for England when she caught Ella Pardy on the line in the women’s ambulatory 200.

Bolt’s blow-up, though, made it all too obvious. The man has said he wants to win often enough. We had been warned. His reaction and TV interview showed just how much. And Nitro II was a better meeting for it.

The loud explosion you just heard was the nitroglycerine in the back of the truck going off.

END

About the Author-

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships and five Commonwealth Games.

He has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.