A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

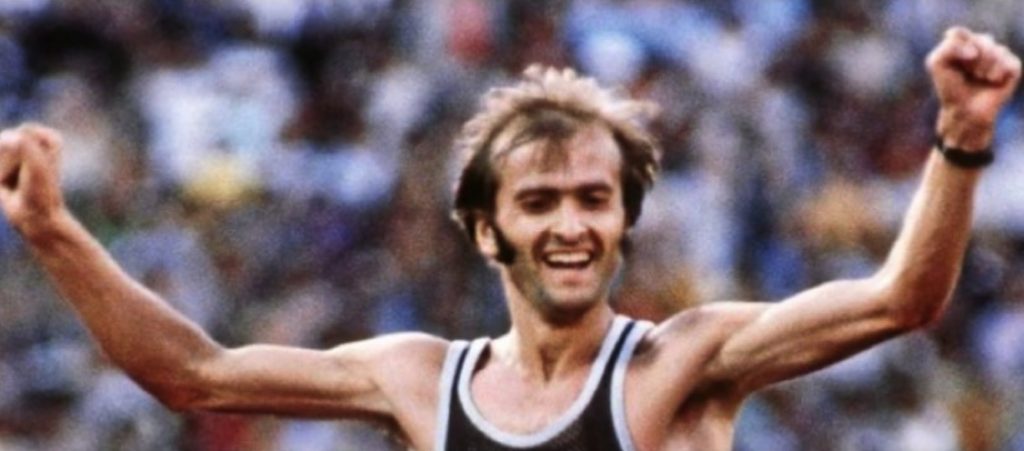

Moscow 1980. Waldemar Cierpinski broke away from Holland’s Gerard Nijboer along the Moscow River late in the race to take his second consecutive Olympic title by around 100 metres.

A more than respectable race. A more than respectable time – two hours 11 minutes three seconds – given the heat and championship conditions. Won by the reigning Olympic champion from the man who, earlier in the year, had become the second-fastest marathoner in history.

In many respects, though, the 1980 Olympic marathon was as much about the race that never was as the race that actually happened. Several factors – politics, the weather, accidents of timing among them – combined to make it a race of greater potential than the one that was actually delivered.

One obvious fact is that Moscow 1980 had a men’s marathon only. It was the last Olympics before women took their rightful place in the Games’ longest running race. Over the next four years – the 1982 European championships, the 1983 world championships, culminating in Joan Benoit’s magnificent debut Olympic marathon win in Los Angeles, women gradually assumed full championship marathon rights.

The weather and tactics naturally played a role. Chris Wardlaw, who ran the race for Australia, recalls it was “bloody hot” on race day.

Rob de Castella made his major championships marathon debut in Moscow. He had run three previous marathons – the 1979 Victorian and Australian championships, and the 1980 Olympic marathon trial – but this one was totally different. ‘Deek’ described it as “crazy”, saying that one moment you would be jogging, the next almost sprinting.

Such surges aside, the pace remained up-and-down, but mostly slow, until Mexico’s Rodolfo Gomez took the lead just before the half-way point. His bravery was not rewarded with a medal. He finished sixth, almost 90 seconds behind Cierpinski.

Moscow, of course, suffered a boycott led by the US as an ill-thought out response to the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. In some events, the boycott scarcely mattered, but it hit the marathon quite hard.

The US Olympic Committee backed the US president before the marathon trial had even been run, but went ahead with the race anyway. Bill Rodgers, one of the world’s best at the time, did not bother running, preferring to race in Boston instead. The ‘Trial’ was won by Tony Sandoval, one of the promising newcomers on the US scene, from Benji Durden and Kyle Heffner. They could have been major contenders in Moscow. Instead, they never got there.

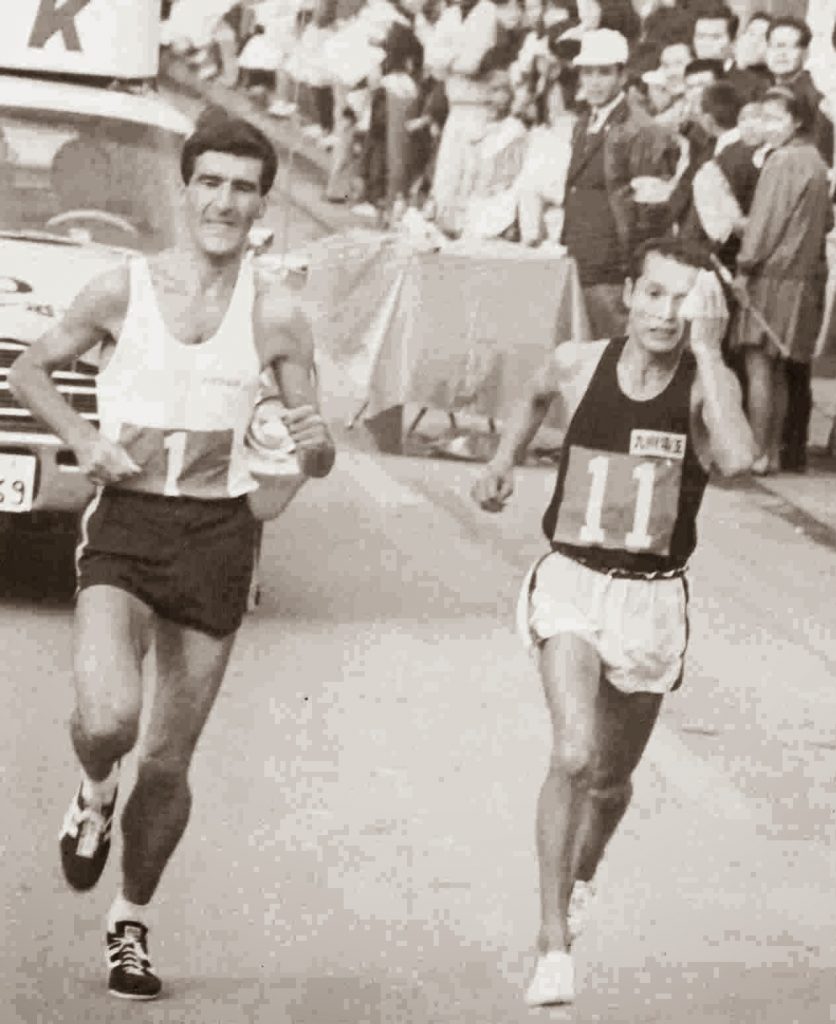

Absent, too, were the Japanese, who would have been led by emerging star Toshihiko Seko. Seko had broken through by winning the 1978 Fukuoka marathon, then won it again the following year. Both times he defeated Cierpinski, along with others who would go on to perform well in Moscow.

Seko didn’t make it either. Instead, he won his third Fukuoka on the trot at the end of the year. Among those behind him were Australians Garry Henry, fourth in 2:10:09, and de Castella, eighth in 2:10:44.

The Japanese also had the Soh twins, Shigeru and Takeshi, who would have been major factors in the Olympic race.

At the time of the Moscow Olympics, de Castella was still developing. He was good, but a long way short of the form which would take him to a world record at Fukuoka in 1981, a Commonwealth Games victory in Brisbane in 1982 and a world championship win in Helsinki in 1983.

Carlos Lopes was no youngster, but in 1980 he had yet to turn his attention to the marathon. He would become a big player in the years 1983 to 1985. Alberto Salazar definitely was a young man, making his marathon debut with a win in New York in 1980.

Ethiopia was not without marathon history in 1980. The east African nation had produced 1960-64 Olympic champion Abebe Bikila, 1968 gold medallist Mamo Wolde and had a number of strong performers around in 1980 (Dereje Nedi finished seventh), but Kenya had yet to get going in the marathon and neither had the impact on the event they do today.

So there were quite a few runners who missed out on being at their marathon peaks in 1980. Everyone knows when the Olympics are on, of course, but a field with Seko, de Castella and Salazar at their marathon best, and also including Lopes, would have made for a sensational race.

The years 1978-80 did bring an advance in times. Derek Clayton had run 2:09:33 at Fukuoka in 1967 and 2:08:34 in Antwerp two years later. For a variety of reasons – some concluded the Antwerp course must have been short, others pointed to Clayton’s incredibly hard training – most marathoners had viewed these times as out of their reach.

But by the late 1970s, athletes were again pushing out towards 2:09. Shigeru Soh ran a sensational 2:09:06 in the 1978 Beppu marathon, going out at a ferocious pace before dropping off world best schedule only in the last five kilometres. Then Nijboer ran a touch quicker – 2:09:01 – in winning the 1980 Amsterdam marathon.

All this could have come to a climax in Moscow – had the politics and the timing been just a little bit better.

Not sure that the Australian contingent had the best preparation — my recollection is that they were required to race in the trial around West Lakes in Adelaide within a week or so of the Aus. track championships where all had raced both 5 and 10 k. Chris Wardlaw should be singled out for his sterling efforts to ensure that we were actually represented in Moscow in face of government pressure to boycott – far from a good lead up.