Written by Daniel Quin – Runner’s Tribe

In Melbourne we are about to enter another Australian Football League finals series and narratives will be formed around Joel Selwood overcoming supposedly epic pain to participate. Or perhaps someone will do a Dermott Brereton and endure after a bone-crunching hit.

The mythology that arises out of these football acts is sometimes overstated. I admire any distance runner who starts a training session or race with the knowledge that it is going to hurt. This knowledge can be debilitating and without good coping strategies, an athlete can unconsciously self-sabotage their training or race in an effort to avoid pain.

When seeking to manage running pain it is essential to distinguish between pain that indicates you should stop running (and seek treatment) and pain that can be worked through. Pain is often an indicator of an injury and therefore it may be disadvantageous, in the long-term, to continue.

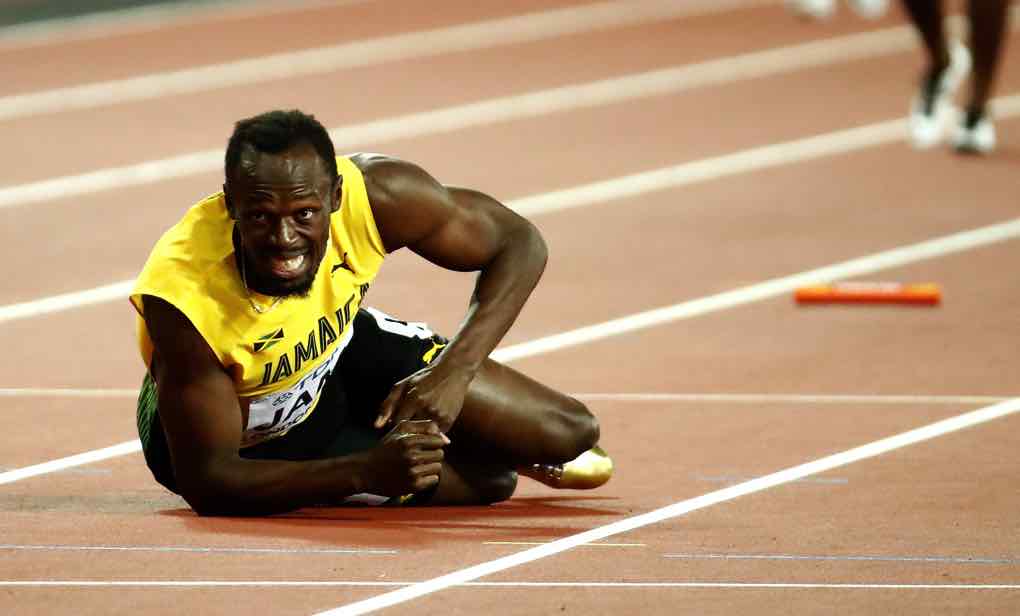

Gabriela Andersen-Schiess in the 1984 Olympic marathon perfectly describes this balance. In summary, she persisted because it was the Olympics, potentially her last race, and others were helping to keep her safe. It would be foolish to ignore this level of pain and risk for a training session.

It is almost impossible to train or race at your best if your thoughts are clouded by: “Stop? Slow down? Or, continue?” The message for an athlete is: be clear why you are racing or training and what level of injury or illness risk is acceptable at that time. Clarity with these goals helps decision making around the stop-slow down-continue dilemma.

One strategy for dealing with the stop-slowdown-continue dilemma is to make a plan. Rehabilitation programs that prescribe work and rest intervals, for example, 10 x 60 second run, 30 second walk, help in two ways. They provide essential progressive physical overload. But more relevant to the current discussion, they provide a structured opportunity to reassess the pain or injury. It frees the mind to enjoy the 60 second run and then the walk is the time for reassessment.

These principles can be applied when unexpected pain crops up in a race or session. For example, an athlete might notice a tight calve early in a race. Upon first noticing this pain most athletes would continue. Having made this decision the athlete needs to return his or her attention to the race (and not the pain). This is the association and disassociation balance I have previously written about.

But what if the pain becomes worse? This is the time to quickly devise a plan. It could be something like, I’ll run to the next aid station, next corner, or for the next 60 seconds and then reassess. But the plan should not be: I’ll constantly worry and assess my calve. Obviously, if the pain changes suddenly a new plan needs to be arrived at…

END OF PART 1 OF 2 (Read part 2 Here)

About the Author: RT columnist, Daniel Quin has run numerous Zatopeks, National XC’s, has raced in a Chiba Ekiden, and won a state 5000m and 15km title. In “retirement” he did a marathon. It hurt! He still runs a fair bit. Professionally Quin is a teacher and psychologist, and researching student engagement- Click Here to Learn more. But the best bit for Quin is being a Dad.

Comments are closed.