By Brad Beer

‘Calf muscle strains’ are a common running injury. They can be debilitating, painful, and require reduced or complete cessation from running. Short and longer lasting episodes of pain can stem from injury to the calf musculature.

The purpose of this blog is to outline the best clinical combined with evidence based approach to rehabilitating calf strains.

‘Calf strain’ is the common terminology runners use when describing a calf muscle ‘tear’. I’m quite happy with the phrase ‘calf strain’ as the term ‘muscle tear’ can be threatening to athletes and runners. For a runner to perceive they have a ‘tear’ may result in the runner feeling vulnerable, or even ‘fragile’, with reduced confidence. This reduction in confidence can manifest as fear avoidance of running, fear of loading the calf musculature through required rehabilitation exercise, and prolong recovery timelines.

a. Calf muscle anatomy

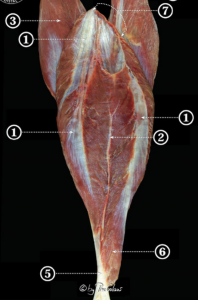

A calf muscle strain can occur to either of the two primary ‘calf muscles’; the soleus or the gastrocnemius (see anatomy images below):

(i) soleus muscle (ii) Gastrocnemius (medial and lateral heads)

The muscles at the back of the leg are comprised of a superficial and a deep group of muscles.

The superficial group is comprised of:

- the soleus and gastrocnemius (pictured above)

- and also the lesser referenced and lesser sized plantaris muscle.

The deep group of calf musculature is comprised of:

- tibialis posterior

- flexor digitorum longus

- flexor hallucis longus

- and the popliteus muscle

Of note anatomically is that within the soleus muscle there are three intramuscular tendinous structures: medial and lateral aponeuroses, and a distal central tendon, shown below:

Soleus intramuscular tendons: (1) medial and lateral aponeuroses, (2) central tendon. Source: HERE>>

The purpose of these three tendinous structures in the soleus is to act like rigid fibrous ‘struts’ to assist the upper part of the soleus to gain more origin (1).

The gastrocnemius and plantaris are biarticular muscles responsible for both knee flexion and ankle plantar flexion. The soleus is a uniarticular muscle responsible for plantar flexion. The plantaris is generally considered a vestigial muscle and provides a weak contribution to knee and ankle flexion when it is functional (2).

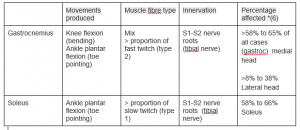

Although the gastrocnemius has a mix of fibers, more are fast twitch (type 2) muscle fibers allowing for explosive/powerful contractions. The soleus is primarily composed of slow twitch (type 1 muscle fibers) and is the key muscle for endurance running.

Runners tend to clump the two superficial muscles together; the soleus and gastrocnemius and collectively refer to these two muscles as the ‘calf’. While there is no ‘real harm’ in this, it does not differentiate in that strains can occur in either or both of these muscles; soleus or gastrocnemius, or far less commonly in plantaris or the muscles of the deep calf group.

Clinically when referring to both the soleus and gastrocnemius they can be collectively referred to as the ‘plantar flexors’.

b. Epidemiology of calf muscle strains in runners

Injuries to the gastrocnemius are among the most common injuries in masters athletes (3) whereas younger runners tend to succumb to achilles tendinopathy. While tears to the medial gastrocnemius and musculotendinous origins tend to be the most common in runners (2).

In the general population the highest risk group is the poorly conditioned male in the fourth to sixth decade of life, incurred typically while doing recreational activity (4). In a study of more than 2000 running-related injuries, gastrocnemius injuries were disproportionately distributed among sex with 70% of the injuries occurring in men (5).

In multiple imaging studies of Achilles and calf muscle injuries, there appears to be a predominance involving the medial head of the gastrocnemius which is involved in 58% to 65% of all cases; the lateral head of the gastrocnemius in 8% to 38% and the soleus in 58% to 66% (6).

Plantaris muscle injuries are the least common injuries and only accounted for 2 (1.4%) of 141 patients in one study (7).

Tears tend to occur in the muscle tissue itself, with a common site of injury being the junction of the muscle into the achilles tendon for both the soleus and gastrocnemius, known as the myotendinous junction.

EXAMPLES OF CALF STRAINS/TEARS

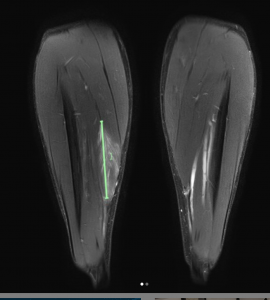

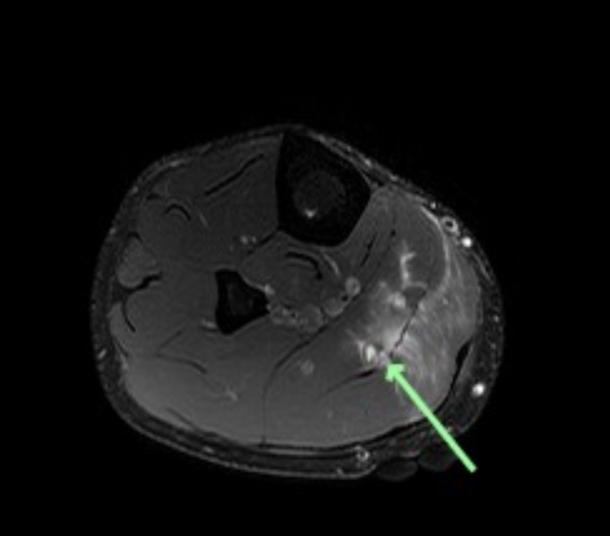

Starains can occur with a vertical muscle orientation such as shown below with the soleus of an Ironman triathlete (former rugby league Australian representative player) who sustained an 11cm vertical tear of the medial and lower 1/3rd of the soleus around the central tendon, less than a week out from his event. See below MRI images:

IMAGES: Q SCAN RADIOLOGY: 11CM (GREEN LINE) WITH 50% OEDEMA OF MUSCLE MASS, AND 5CM DISRUPTION OF CENTRAL TENDON

I also recently consulted with a professional triathlete from the UK who had sustained an 8.5cm vertical tear of the soleus.

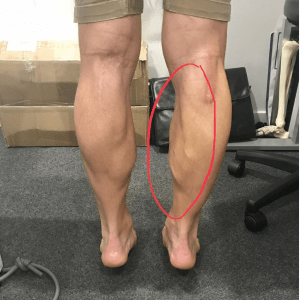

Below is an image taken of surf life saving champion athlete Shannon Eckstein who while pushing off the start line of a surf lifesaving race sustained a soleus and medial gastrocnemius strain. On MRI there was a vertical tear of 15cm in length and 50% of the muscle mass was oedematous (tissue swelling and fluid). Radiologists diagnosed the injury as a Grade 3b partial thickness intramuscular tear of soleus and medial gastrocnemius. The below image shows the degree of muscle atrophy (wasting) evident approximately 8 weeks after the injury which ended the athlete’s season.

c. The role that the ‘calf’ plays in running

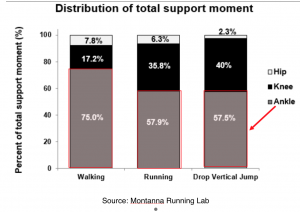

Greater than 50% of running force propulsion is generated from ‘below the knee’ plantar flexor musculature. Given the force developed by the calf it is understandable that the calf can be a potential site of muscular injury for a runner.

Interestingly many runners believe the hip musculature to be the primary force producers for running propulsion, however researchers have shown that circa 5-10% only of force production comes from the hip musculature, with the bulk of work being done below the knee (ie plantar flexors), followed by propulsive force from the knee musculature. See below from Dr Rich Willy and his Montanna Running Lab team:

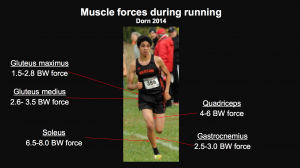

It’s also interesting to note the high peak muscle forces that the runners body generates. The image below illustrates the large peak muscle force that the soleus generates as a multiple of body weight 6.5-8x body weight, with the gastrocnemius also generating large peak muscle forces of 3.5-4.0x body weight.

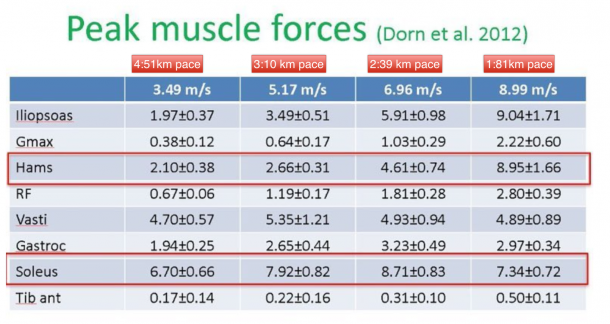

Furthermore when looking at peak muscle forces per muscle group across a variety of running speeds it is evident that the soleus muscle is generating high peak forces across all speeds, see image below:

d. The role of imaging calf strains

Imaging of the injured area of the calf is contextual to the presenting injured runner. In my clinical experience most runners will not require or benefit from imaging to the region (ultrasound or MRI).

However occasions when imaging may be required can include:

- when the runner has sustained an injury close to an event and a prognosis /recovery time needs to be known

- when a runner is insistent they need one (certain personality types just need to ‘see what I have done’ and such runners tend to often be more ‘bought into’ the required rehabilitation program when they have confidence in the diagnosis and comfort in knowing that there is a diagnosis)

- Lack of clarity of diagnosis (ie more than one muscle can be affected with some injuries)

- Runner is struggling to achieve desired rehabilitation outcomes

Most runners are happy to not undergo imaging when an explanation regarding their injury is given.

e. Diagnosing a calf strain

Diagnosis of calf muscle strains tends to be quite straight forward. Diagnosis is made on the basis of a combination of reported history and physical examination.

Mechanism of injury

The runner will typically report an acute onset of pain in the region of the calf brought on by activity, often times jumping or accelerating when running. For runners the injury more frequently arises during faster interval training, racing, or high-speed tempo runs.

Clinically many runners also report no recallable moment of acute pain, but rather a progressive tightening sensation in the calf that escalates to the point of pain with attempted running and possibly walking.

Injury to the soleus may occur with fatigue or overtraining so that the runner may not recall an acute event but experiences progressive calf pain that ultimately becomes too limiting to allow normal running. Marathoners may often have onset of calf pain within the first 24hours after their long run or even after a race.

A runner that cannot continue to run and pulls up limping at the time of injury is likely to have incurred a greater grade injury than the runner who feels a ‘pull’ and is able to run on. Severity of strain tends to be linked to recovery timelines as prior outlined.

If there is not a recallable moment or mechanism of injury linked to exertion (activity/movement of some kind) than it is possible that the diagnosis of a calf strain may need reconsideration.

Other potential calf conditions can include:

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Deep vein thromboembolism

- Neural conditions including peroneal, sural, or tibial nerve entrapments/ irritations.

- Claudication conditions including popliteal artery entrapment/syndrome

- Bone sarcomas of the tibia

Physical Examination

Physical examination occurs in combination with a detailed history of the injury and will centre on functional tests of increasing demand on the plantar flexors to elicit any reproduction of symptoms.

The severity of injury will determine the type of findings on examination:

- Milder injuries will show tenderness to palpation, pain with resisted muscle testing but no visible swelling, discolouration or defects

- More severe injuries show significant tenderness to palpation, discolouration and swelling, and sometimes a visible defect.

- Tenderness for gastrocnemius injuries typically localises at the distal insertion of the medial or lateral head into the proximal Achilles fascia.

- Tenderness for soleus injury is palpated deep and often distal to the muscle bellies of the gastrocnemius on either medial or lateral leg.

- Popliteus injury tenderness is deep and often at the intersection of the two gastrocnemius heads or along medial proximal Achilles tendon.

Ensuring the Achilles tendon is intact by performing the Thompson’s test is imperative. The Thompsons test has been shown to have a 96% sensitivity and 98% specificity with regards to detecting achilles tendon ruptures (8).

f. Classification of calf strains

For years the tradition of classifying muscle injury was that of three grades: 1-3. The higher number represented a higher degree of muscle strain; minor, moderate, and complete injury.

However this classification system lacks diagnostic accuracy and therefore provided very little prognostic information to treating practitioners.

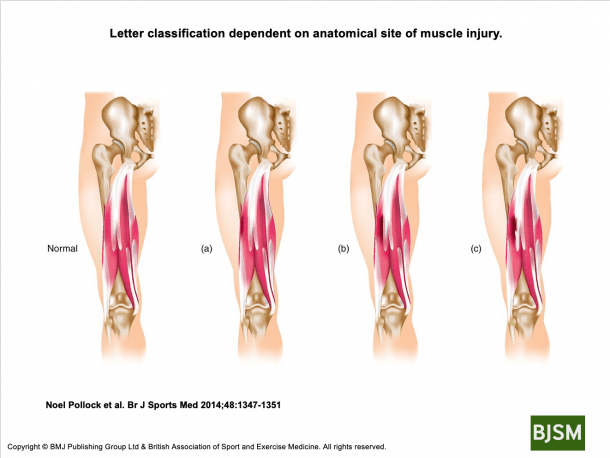

In 2014 the 5 grade British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification was proposed as a new evidence based grading system aimed at improving diagnosis and therapeutic decision making.

Injuries are graded 0-4 based on MRI findings for ‘extent’ of injury. Additional suffixes are added for the ‘site’ of injury as follows:

- (a) myofascial injury in the periphery of the muscle

- (b) musculotendinous injury within the muscle belly. Most commonly at the muscle tendon junction. These are the most common injuries.

- (c) intratendinous injury-ie extends into the tendon. Associated with a poorer prognosis and longer recovery times.

British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification also uses an additional descriptor included in the classification to denote the site of injury (proximal, central or distal third) relative to the muscle origin.

Since the Classification model was proposed in 2014 (10) it has become the accepted best practice for classifying muscle injuries including those to the calf musculature.

g. Calf muscle strain prognosis

The greater the degree of muscle strain the greater the time to rehabilitate fully and return to normal training loads.

All calf strain recoveries are individualised with recovery times varying from runner to runner.

The most common site of muscle injury is at the musculotendinous junction (ie ‘b’ classification) and this may be associated with more prolonged and different rehabilitation requirements than a peripheral myofascial injury (10). Furthermore, there is also evidence that injury within the tendon (i.e. ‘c’ classification) is associated with a poorer prognosis (10).

As a general guide for recovery timelines predicting time for complete recovery can be difficult due to the many moderating factors, including athlete age, injury history, muscle involved, pre injury tissue capacity etc. Instead I find it clinically more meaningful and helpful to outline approximate time frames to return to easy running -which initially may include walk-running.

The following may serve as an approximate guide:

- Grade 1: 1-2 weeks to return to some running

- Grade 2: 2weeks+ to return to some running

- Grade 3: 3-6 weeks to return to some running

- Grade 4: 3months+ to return to some running

With recommencing running it is important to find the right balance between being too overzealous and returning with too much running too soon and flaring symptoms, and being too conservative and reducing tissue capacity of the affected area and rest of the running body beyond what could have been prevented had a return to run program commenced sooner.

Of course the more deconditioned a runner becomes through injury the longer timeframe required to return to full training loads.

h. Who can be affected by calf strains?

Calf strains can occur to any runner. Runners of all abilities: beginner, recreational, recreationally competitive, and the elite, can incur a calf strain.

Calf muscle strains can occur any age, however the incidence of calf strains can increase as a runner enters their masters years (> 35 years of age). As prior outlined there is a higher prevalence of calf strains for male runners (5).

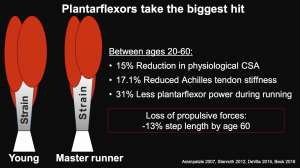

As a runner matures there is a substantial reduction in force production of the plantar flexor musculature.

The slide below from Dr Rich Willy’s presentation at the 2018 La Trobe Running Symposium outlines the changes that happen at the calf between 20 and 60 years of age. This reduction in calf capacity leaves the masters runner more ‘vulnerable’ to calf and or achilles injuries than a sub 35 years of age runner.

As the runner matures there is also reduced overall leg stiffness, which can result in a less stiff achilles tendon, and greater excursion of the calf muscular eccentrically on landing. Willy & Parquette (9) reported that calf strains are more common in the masters runner due to this greater eccentric elongation of the calf musculature-which equates to a heightened risk of injury.

There are no reported specific anatomical risks which predict calf injury (2).

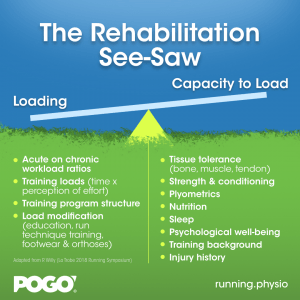

Most strains (muscle tears) are caused by a simple mismatch between loading and a runner’s capacity to deal with that given load. The diagram below illustrates the relationship between loading and capacity, whereby various moderating factors determine the load and capacity of a runner at any given time.

A great resource that expands upon the above diagram is a video produced by Kevin Maggs of Running Reform which can be viewed below:

In simple terms when the task being performed by the runner exceeds the tissue tolerance or capacity of the calf musculature a strain or injury may result. This exceeding of tissue tolerance of the calf musculature can come as repetitive and therefore relative overload of the tissue through multiple repetitions, or as a one off absolute overload-such as attempting to sprint or run at high exertion.

Training errors are known to account for 60% of all running related injuries (11) and must therefore be considered in terms of both prevention and treatment of calf injuries.

Training errors can include; sudden increases in running workload (sessions, volume, intensity, terrain, or a combination) that can result in heightened injury risk.

Injury risk factors such as often cited ‘old shoes’, inappropriate footwear, and running technique, tend to often be over attributed in importance as factors contributing to the onset of calf muscle strain. I’ve seen many runners with calf strains present for physiotherapy believing that they should have replaced their running shoes sooner, and citing the ‘old shoes lacking support’ as the chief reason for injury onset.

Clinically one of the key reasons I believe runners develop calf strains is a deficit in plantar flexor (calf) strength. Many runners are surprised to learn that they in fact have ‘weak calves’ through assessment, believing that because of the many repetitions of contraction the calves go through with running, that they would have ‘strong calves’.

However this is not the case. Running does not strengthen calves per se, rather designated conditioning work is required.

j. Assessing the capacity of the calf musculature

In clinical practice I use two types of tests to assess and where possible benchmark a runner’s plantar flexor capacity: body weight tests and also loaded tests. The aim of these tests is to establish the ‘load tolerance’ of the calf musculature (gastrocnemius or soleus). This can be done initially on examination of the injured runner who has just sustained a calf injury (if tolerated) or as rehabilitation commences and progresses.

(i) Body weight tests:

STANDING SINGLE LEG CALF RAISE (HEEL RISE) TEST.

The runner rises up and down pushing through the first and second toes to a 2s up, 2s down tempo. This is ideally completed without shoes with weight being centred through the first and second toes. Pain on this test may implicate the gastrocnemius (vs soleus). The assessor needs to monitor quality of movement (any compensation strategies eg bending the knee, rolling onto outside of foot, rocking the body forwards to generate momentum) and symmetry side to side.

Known benchmarks exist from the literature for the median number of reps for different age decades as listed below -sourced from Hebert-Losier et al (12):

- 20’s: male (M) 38, female (F) 31

- 30’s: male (M) 33, female (F) 28

- 40’s: male (M) 29, female (F) 25

- 50’s: male (M) 24, female (F) 23

- 60’s: male (M) 20, female (F) 20

- 70’s: male (M) 15, female (F) 17

- 80’s: male (M) 10, female (F) 15

Clinically I like to see all runners be able to complete 30 continuous repetitions with good form, and arbitrarily use the following assessment criteria:

- < 15 reps (poor)

- 15-30reps (satisfactory)

- > 30reps (good)

- a difference of greater than 5 reps side to side can signify significance and needing to address the asymmetry

STANDING BENT KNEE TEST

Performed as above but with a bent knee and support from a wall/object. This test targets the soleus. The knee bend angle must be at least 60degrees to target soleus. There are no normative data sets available for this test. Clinically I prefer to use the loaded soleus test as outlined below. However this test can be used if availability to equipment for loaded testing is not available.

STANDING DOUBLE LEG CALF RAISE TEST

If the runner cannot tolerate single leg testing then double leg testing can be used. One drawback with double leg testing is that it does not isolate each side to determine side to side differences in calf capacity, and does not provide an accurate or useful guide of the affected calf strength. It can however be used in the instance of substantial calf injuries where the runner is experiencing marked pain and/or has low confidence in plantar flexing the ankles. I would however progress to single leg assessment as soon as able.

(ii) Loaded tests:

These tests involve capacity testing above body weight through either the use of resistance by way of holding onto dumbells or resistance through machines such as those found in a gym: seated calf raise machine, or a smith rack. These loaded tests can be performed as follows:

STANDING SINGLE LEG CALF RAISE

Using a smith rack and step rise up and toe with 2s up, 2s down tempo until fatigue. The assessor and runner are looking to determine the 8rep maximum (ie resistance that can be moved to complete 8 quality reps).

Malliaras in his Mastering the Lower Limb Tendinopathy workshop cites a target of 0.3-0.4x body weight as external load. For example an 80kg runners would look to perform 4 x 8-12reps of 27kg external loaded calf raises single leg.

This test can also be performed in a calf raise machine, and also from the floor rather than a step.

SEATED SINGLE LEG CALF RAISE

Sitting in a smith rack or seated calf raise machine and using a piece of wood for leverage rise the knee up and down against resistance. The assessor and runner are looking to determine the 8rep maximum (ie resistance that can be moved to complete 8 quality reps).

Malliaras in his Mastering the Lower Limb Tendinopathy workshop cites a target of 1.0-1.5x body weight as external load.

k. Rehabilitation of calf strains

I coach injured runners that three key principles are required for the rehabilitation of calf injuries to progress well. They are:

- Time: rehabilitation can’t be ‘crammed’-time is required for the body to progressively adapt to loading stimulus.

- Compliance: the runner must use ‘best efforts’ to get the rehabilitation program completed. Many runners feel that they must complete a perfect ‘check list’ of exercise completion-however this is rarely possible. Rather being prescribed a realistic program for the given runner’s lifestyle that still ensures required strength gains are achieved is key.

- Progressive loading: perhaps the two most common errors I see for runners rehabilitating injuries is that the rehabilitation program may at times fail to be progressive (ie incrementally more challenging), and the degree of challenge too low-meaning that the injured runners is underloaded throughout rehabilitation. The effect of these two rehabilitation errors can be prolonged recovery timelines and heightened risk of re-injury.

The successful rehabilitation of calf strains for runners involves the following stages:

- Settling initial symptoms down

- Progressively increasing calf musculature capacity through progressive loading exercises

- Return to running

The stages are not mutually exclusive, and progression to the next stage is not time dependent. Rather progressing will depend on the runner/therapist doing so based on clinical criteria being set and assessed against.

Let’s explore the 3 phases:

1. SETTLING INITIAL SYMPTOMS DOWN

The first aim of rehabilitation is to ‘calm down’ the aggravated and painful soft-tissues that have been strained. Reducing pain and symptoms may be achieved by off loading the strained calf musculature through rest, taping techniques, and appropriate soft tissue massage techniques. While somewhat lacking scientific evidence for soft tissue recovery modalities such as dry needling or western acupuncture can be popular amongst runners and may also be useful.

Medication (analgesia) can be used if pain levels are not tolerable for mobilising with walking. Crutches or walking aid use is dictated by the pain tolerance of the individual/combined with the degree of calf strain.

While the above strategies can be important for settling symptoms and pain resulting from the injury, progresive strength work for the calf musculature remains the foundation for successful calf strain rehabilitation.

2. PROGRESSIVE LOADING EXERCISES

Building strength and tissue resilience/load capacity of the calf musculature is the foundation of successful calf muscle strain rehabilitation. No amount of soft tissue massage or stretching (which are popular runner’s self care strategies) will in isolation rehabilitate a runner’s calf strain.

Loading the calf and exposing it to stimulus as soon as possible is key to a successful and timely rehabilitation outcome. Some runners delay loading the calf due to fear/apprehension and as a result incur greater deconditioning through disuse than what could of been avoided. This can also be the case with returning to initial running. Reluctant and apprehensive runners risk delaying overall recovery timelines if a too cautious rehabilitation approach is taken. This too conservative approach can be the work of the supporting therapist or the runners themselves.

Calf rehabilitation exercises will involve home based exercises typically followed by gym based exercises (where possible).

Home based exercise has the benefit of low barriers to completion and are good for restoring some early load tolerance to the affected tissue. However a ‘ceiling’ of maximally achievable strength gains may occur when a runner rehabilitating a calf strain does not enter a commercial gym facility or engage in rehabilitation exercises with suitable resistance.

Home exercises and appropriate progressions

Below are examples of home based rehabilitation exercises I commonly prescribe for runners rehabilitating calf strains. I have listed these in approximate order of difficulty, however working through these, or selecting which ones to perform will be based on individual or therapist preferences and clinical context.

- Standing calf raises double leg

- See above video for assessment and instructions

- Prescription: may commence with 3×12-20reps and as load is added (via weight or slowing down exercise) progress to 3-4 sets of 6-8reps

- Progressions can include slow time to rise, holds at the top, slow descent*, moving onto a step edge from the flat ground, faster concentric phase (rising up), adding resistance (eg backpack)

- Standing calf raises single leg

- See above video for assessment and instructions

- Prescription: may commence with 3×12-20reps and as load is added (via weight or slowing down exercise) progress to 3-4 sets of 6-8reps

- Progressions can include slow time to rise, holds at the top, slow descent, moving onto a step edge from the flat ground, faster concentric phase (rising up), adding resistance (eg backpack)

- Soleus wall sits double leg

- Prescription: may commence with 2-5x30s holds and progress to 1min holds (or even longer)

- Progressions can include sitting deeper on the wall, pulsing up an down with the heels, holding onto resistance, progressing to a single leg

Toe taps

- The aim of toe taps is to remain as high on the toes as possible between reps and now drop down with height.

- Prescription: aim for 4s holds at the top and then shift weight to the other side (not dropping down with the heels)-commence with 1 set of 20-30reps and add sets eg 2-3sets.

- Toe walks

- Simply walk around up on the toes with emphasis of weight going through the 1st and 2nd toes.

- To progress walk more slowly and aim to maintain the height of heel lift

- Prescription: work off time eg start with 2-4sets of 15-30s walks

- Double leg pogo jumps

- Simply bounce up and down on two feet-with slight knee bend-aim to keep the contact time with the ground short

- Prescription: runners can work off time or reps. I prefer time eg 4x15s > 4x30s> 2x1min etc

- Progress by advancing to single leg pogo jumps -commence with reps

- Note: the addition of such exercises (plyometric) to a program is key-many runners overlook working on plyometric exercises for calf strain rehabilitation until later in the program, or often times it can be completely ignored.

- Forward hops double leg

- To progress from jumping up and down, add in moving forwards with the jumps, start small initially and add distance, before progressing to a single leg

- Prescription may include: 3-4 sets of 6-10reps

- Skipping

- Skipping is an often underrated exercise for runners-and can be very beneficial for runners rehabilitating calf strains.

- Prescription is time based: eg 3-4 sets of 30-60s, or even 2min set(s)

- Progression may include: double unders, or single leg

*Time under tension is a principle that can increase loads through the calf musculature and therefore facilitate strength gains and heightened load capacity of the calf. Time under tension through the slowing down of exercises is a good way of progressing both home and gym based exercises. Practically this may look like performing an exercise for 2-3 seconds up (concentric) and 2-3s down (eccentric). Longer hold time may be appropriate in some instances.

GYM STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING EXERCISES AND PROGRESSIONS

Willy and Paquette (9) state that evidence clearly indicates that slow and heavy resistance training has a large and beneficial effect on muscle qualities, tendon stiffness, and running performance. Practically this would look like completing 3 to 4 sets of 6-8 repetitions, completed 2-3 times per week. By contrast Willy & Paquette report that high repetition and light resistance training while useful and necessary in early calf strain rehabilitation is unlikely to be as effective in improving the calf muscle capacity as it also has a negligible effect on tendon stiffness.

- Standing calf raises

- These can be performed as single leg calf raises initially to isolate the musculature and give the runner an appreciation of any side to side differences that may exist. In latter stages of rehab/return to running double leg calf raises can be added with loads equalling body weight or even greater.

- These can be performed with straight leg (gastroc focus) or bent knee (soleus).

- Calf raises can be performed in a smith rack* or standing calf raise machine. I personally prefer runners to work in a smith rack-as I believe it afford greater control, however the calf raise machine is a valid option.

- Aim to control movement up and down and have the leg straight-ie no bending at the knee. Push through the 1st and second toe, and aim for maximal heel lift.

- Can be performed off the ground or off a small step-I find starting off a small step affords greater leverage than off the floor (and may therefore be better for the single leg version)

- Prescription:. A target for this exercise with regards to load is 0.3 x body weight being able to do 4sets of 6-8reps single leg. Double leg loads can be 1.0-1.5x bodyweight 3-4sets of 6-8reps.

- *Note: the bar of a smith rack is typically 20kgs

Seated calf raises

- These can be performed as single leg calf raises initially to isolate the musculature and give the runner an appreciation of any side to side differences that may exist. In latter stages of rehab/return to running double leg calf raises can be added with loads equalling body weight or even greater.

- Seated calf raises can be performed in a smith rack* or a seated calf raise machine. I personally prefer runners to work in a smith rack-as I believe it afford greater control, however the calf raise machine is a valid option. Seated calf raise machines can also be quite difficult to find in many gyms.

- Aim to control movement up and down and have the bar resting as far down the thigh as possible (note: a tolerance to the pressure on the thigh does build up-however padding is a must!)

- Push through the 1st and second toe, and aim for maximal heel lift.

- Can be performed off the ground or off a small piece of timber or weight plate on the ground.

- Prescription:. A target for this exercise with regards to load is 1.0-1.5 x bodyweight being able to do 4sets of 6-8reps. Double leg loads may be as high as 1.75-2.0 x body weight eg 3-4sets of 6-8reps.

- *Note: the bar of a smith rack is typically 20kgs

Loaded plant walks

- This exercise can be performed with a barbell on the shoulders

- Aim to pull the toes firmly towards the shin and rapidly ‘slap’ the foot down

- Barbell weight can start as low as 10kgs and progress to an Olympic bar (20kgs) + additional external loads (eg 10kgs each side)

- Prescription: may commence with 6 x 5-10m walks

Single leg step hop ups

- While this could be performed as a home based exercise I tend to prescribe it as part of a gym session as it is quite challenging (ie does not belong in early stage rehabilitation) and also because the runner requires a small step (eg aerobics step) which are readily available in gyms

- Prescription: may commence with 3-4sets of 6-12 hops

- Progression may include jumping onto a higher step

3. RETURN TO RUNNING

Every injured runner wants to know when they can return to some running. There are no hard and fast nor clinical guidelines or published best practices to follow when it comes to commencing some running while rehabilitating the calf strain. It is up to the treating therapist and runner to collaboratively device a program that can reintroduce the runner to some tolerated running loads.

Some principles to keep in mind with this phase of rehabilitation are:

- Don’t leave it too late-this will delay overall recovery and heighten frustration. I often say you don’t want to be too conseravtive or too reckless-however aiming for the ‘middle ground’ can be a good strategy.

- The runner’s goals, possible event timelines and preferences. Some runners may prefer to wait while others may be impatient and pushing to start.

- Minimum criteria I like to see runners achieve before commencing running include: pain free walking and the ability to single leg hop 10 times without pain.

- It is important to coach the runner that if a flare in symptoms does occur that this does not necessarily mean the calf has been ‘retorn’ or that they have returned to ‘square one’ with their rehabilitation. It can be common to feel heightened sensations of tightness and some discomfort in the region of the strain when a return to run program is initiated.

- Walk/run programs are a great way to commence some running. Prescription can vary however a good starting option may be:

- Week 1 3 walk/runs: 30s (jog/run), 4.5mins walk repeated for 30mins

- Each week add 30s of run time while decreasing walk time by 30s

- By week 9 30mins of continuous running will be achieved

- The above program is quite conservative -there are many instances in practice where I will prescribe larger initial running periods and smaller walking periods for example commencing with 2-5min run times

- Progressing a runner as soon as possible to be able to achieve 10mins> 15mins> 25min> 30min> up to 60min continuous running is both motivating for the runner and are important milestones on the way to a full return to training loads.

- Many runners want to add speed work in too soon. Speedwork increases force production from the calf musculature and may therefore provoke symptoms if commenced too soon in a return to run program. My normal guideline is to build volume back to full or near full training volume, before speed is reintroduced.

l. Recurring calf strains

There are a subset of runners who experience recurring calf strains. Such runners tend to lose confidence in their calf musculature and can feel ‘vulnerable’ with regards to anticipating further calf strain incidents.

The runner who experiences recurring calf strains usually has quite a high degree of frustration. Clinically I have observed recurring calf muscle strains more common amongst masters level athletes.

From years of clinical observation on assessment the runner who has been experiencing ongoing calf strains will typically have a deficiency in their plantar flexor (calf) strength. This deficit can be determined through the above calf capacity tests, and may involve either the gastrocnemius or the soleus muscles.

Once this or these deficits have been identified, I find the frustrated runner’s ‘lights go on’ as they can experience the strength deficits side to side, or against known benchmarks for age. Rehabilitation should then target the strength deficiencies as outlined above. Once strength deficits are addressed the recurrence of strains tends to drop off or be completely ameliorated.

m. Calf rehabilitation mistakes to avoid

I observe several key mistakes frequently made with the rehabilitation of calf strains. These can include:

- Over attributing importance to stretching

Across the board I tend to observe runners who have incurred a calf strain almost intuitively begin stretching the calf believing that stretching will be beneficial. My clinical experience is that stretching of the calf particularly in the symptomatic stage of recovery can at times be provocative of pain and symptoms. The recovering runner is better to attribute time to strength and resistance training to restore the load capacity of the injured calf musculature.

- Over attributing importance to foam rolling

The same goes with foam rolling of the calf-while foam rolling isn’t necessarily harmful for the calf, to prioritise time to rolling at the neglect of strength exercises, which I often observe happening is a mistake.

- Not progressing to hard enough exercise loads

While being able to complete body weight exercises eg calf raises is a key part of successful calf strain rehabilitation, a common failing I observe in clinical practice is not progressing gym rehabilitation to hard enough levels. The benchmarks set for sufficient load capacity I like to employ in practice are listed below. Note that these are high levels of strength. Failing to reach or move towards these through rehabilitation may heighten risk of ongoing calf strain symptoms or possible injury recurrence.

n. In Summary

The mainstay of successful calf muscle rehabilitation following a strain is a progressive strength program targeted at both increasing and optimising the load capacity of the calf musculature. This will take many weeks of progressions and consistent completion for both home and gym based exercises. The runner who fails to restore the load capacity of the calf musculature may experience ongoing symptoms or possibly even injury recurrence by way of recurring strain or strains.

Other benefits of calf strengthening

High plantar flexor function seems to be protective against achilles tendinopathy. Willy and Paquette in their review of masters runners state ‘runners with greater eccentric plantarflexor strength and greater propulsive forces during running have a reduced risk of developing achilles tendinopathy (9).

Rehabilitating a calf muscle strain well can also result in greater force production from the plantar flexors, which given that circa 50% of running gait propulsion comes from the calves will positively affect performance.

Related

- Say goodbye to recurring calf strains blog HERE>>

- Masters runners blog HERE>>

- Strength and Conditioning for Runners podcast HERE>>

Brad Beer (APAM)

APA Titled Sports & Exercise Physiotherapist (APAM)

B.Physio/ B. Ex. Sc

Author ‘You CAN Run Pain Free!’

Founder POGO Physio

Host The Physical Performance Show

References

- Brukner, P, Khan, K (2017) Clinical Sports Medicine, 5th Edition.

- Fields, Karl B. MD; Rigby, Michael D. DO (2016). Muscular Calf Injuries in Runners. Current Sports Medicine Reports: September/October – Volume 15 – Issue 5 – p 320–324

- McKean KA, Manson NA, Stanish WD. Musculoskeletal injury in the masters runners. J. Sport Med. 2006; 16:149.

- Gallo RA, Plakke M, Silvis ML (2012). Common leg injuries of long-distance runners: anatomical and biomechanical approach. Sports Health. 4:485–95

- Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, et al (2002). A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. J. Sports Med. 36:95–101.

- Counsel P, Comin J, Davenport M, et al. Pattern of fascicular involvement in midportion Achilles tendinopathy at ultrasound. Sports Health. 2015; 7:424–8.

- Delgado GJ, Chung CB, Lektrakul N, et al. (2002) Tennis leg: clinical US study of 141 patients and anatomic investigation of four cadavers with MR imaging and US. Radiology. 224:112–19.

- Maffulli N. (1998) The clinical diagnosis of subcutaneous tear of the Achilles tendon. A prospective study in 174 patients. J. Sports Med. 26:266–70

- Willy R, Parquette M. The Physiology and Biology of the Masters Runner

- Pollock N, James SLJ, Lee JC, et alBritish athletics muscle injury classification: a new grading systemBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:1347-1351.

- Hreljac A. Etiology, prevention, and early intervention of overuse injuries in runners: a biomechanical perspective. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2005;16(3):651–vi. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2005.02.002

- Hébert-Losier K, Wessman C, Alricsson M, Svantesson U. Updated reliability and normative values for the standing heel-rise test in healthy adults. Physiotherapy. 2017;103(4):446–452. doi:10.1016/j.physio.2017.03.002