A column by Len Johnson – Runner’s Tribe

Damn you Eliud Kipchoge! There was Berlin 2017 poised to demonstrate all over again the glorious uncertainty of the marathon and you had to go and ruin it.

Kipchoge being the great athlete he is, there was more enough compensatory glory in the way he chose to ruin things, clawing his way back from a deficit of up to 25 metres at times in the last five kilometres to win.

Until then, however, Berlin had seemed likely to provide one of the bigger boilovers in recent marathon history, with marathon debutant Guye Adola throwing down the gauntlet to Olympic champion Kipchoge as they raced past 35km. This act of lese majeste followed the earlier demise of the world’s greatest distance runner, Kenenisa Bekele, and the penultimate holder of the world record, Wilson Kipsang, both gone by 30km.

Now Adola threatened to completely overturn the established order by beating the man who all but broke two hours earlier this year. This couldn’t happen, could it? Well, ultimately it didn’t, but as the Duke of Wellington said after the Battle of Waterloo, it was a near-run thing.

Berlin has made a thing of world records, with no fewer than 10 being set there, five of them coming in the past 10 years and all but one in the past 20. With the second (Bekele), third (Kipchoge) and equal fourth-fastest of all time (Kipsang), Dennis Kimetto’s world record 2:02:57 was under serious threat at Berlin 2017.

But there’s a danger in world record hype which has caught Berlin out before. In 2009, when Haile Gebrselassie won for the fourth time in a row (two of those in world record performances), chances of a world record melted as the sun shone brightly and Berlin produced neither a record, nor an exciting race.

But for Adola, Berlin 2017 may have gone down the same path. Once Bekele proved to be not in good shape – leading to his long-time manager, Jos Hermens, to question his “professionalism” – and Kipsang succumbed to the conditions – there would have been no race but for Adola. And the insidious impact of lingering humidity from heavy overnight rain, not to mention puddles on the roads, proved enough of a brake on times to put the world record (just) out of reach,

Adola’s putting the question to Kipchoge in the closing stages pushed all that to one side. The winner of London and the champion of Rio in 2016, the man of the Monza 2:00:25 earlier this year, was suddenly under more pressure than he had been in any of those races.

Rallying strongly in the final kilometres, Kipchoge came through to win comfortably enough in 2:03:32. Only in the era of four very special Ks – Kipchoge, Kipsang, Kimetto and Kenenisa – could anyone be even mildly disappointed with such a time, and what a race we had by way of compensation. Perhaps the best thing about Kipchoge’s run was that, in the end, he made victory seem as if it had been inevitable all along when it certainly was not.

As much as the conditions, competition may have played a part in moderating the time. Both the men’s and women’s race slowed as more than one athlete remained in contention for the win almost until the finish at Brandenburg Gate. The men slowed from 14:40 for 30-35km to 15:04 from 35 to 40km as Adola fought it out with Kipchoge. Kipchoge then sprinted home in 6:24 (just over 14:30 pace) over the last 2.195km.

It was a three-way battle in the women’s race before defending champion Gladys Cherono prevailed in 2:20:23, from Ruti Aga, 2:20:41, and Valary Aiyabei, 2:20:53. Again, the slowest 5k split was from 35 to 40.

In the end, then, the established order prevailed in both races, but Berlin 2017 was a timely reminder that the marathon can be, and remains, glorious in its uncertainty. From the Athens Olympic marathon of 1896, when Spiridon Louis came home to a hero’s welcome, passing Australia’s Edwin Flack, among other putative winners, as he came through the field, right through till recent times, there have been as many bolters as favourites salute the judge.

Zatopek was a champion distance runner, but it was still an upset when he defeated the world’s best marathoner, Jim Peters of Britain, to complete his distance treble in Helsinki in 1952, as it was when Alain Mimoun beat Zatopek in Melbourne four years later. Abebe Bikila in Rome 1960 and, in the women’s race, Constantina Tomescu in Beijing and Tiki Gelana in London were all surprises when they happened.

Then there is the man whose image was engraved on the Berlin finisher’s medals this year: Josia Thugwane comprehensively upset the favourites to win in Atlanta in 1996. None of these results would have sent any bookmaker to the wall.

Australians did well in Berlin, perhaps inspired by Steve Moneghetti’s induction into the race’s newly-established Hall of Fame. Liam Adams finished ninth in a PB 2:12:52, one of four Australian men – David Criniti, Julian Spence and Mitch Brown the others – to go under 2:20. Ellie Pashley (nee O’Kane) improved over 10 minutes to 2:35:55 in the women’s race.

Finally, some 46 (all men on this occasion) finished under 2:20 in Berlin, which strikes me as a big number these days. London, back in its third edition in 1983, had 93, which to my limited knowledge was, and remains, the most in any marathon.

End

About the Author-

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships, and five Commonwealth Games.

Len Johnson wrote for The Melbourne Age as an athletics writer for over 20 years, covering five Olympics, 10 world championships, and five Commonwealth Games.

He has been the long-time lead columnist on RT and is one of the world’s most respected athletic writers.

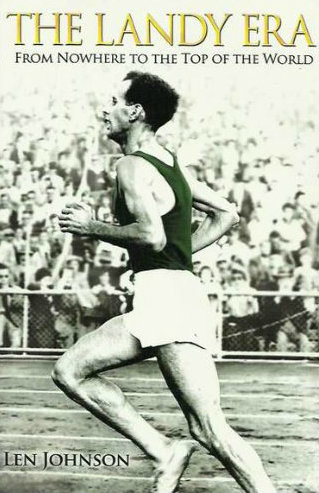

He is also a former national class distance runner (2.19.32 marathon) and trained with Chris Wardlaw and Robert de Castella among other running legends. He is the author of The Landy Era.

Top 10 in Berlin – Interview with Aussie Olympic Marathoner Liam Adams

Interview with Australia’s Ellie Pashley post Berlin Marathon- 2:35:55, CG qualifier & 13th overall

Interview with Marathoner & Run Beyond Project founder David Criniti

Thanks for the article in which I enjoyed reading. I’ve been interested in “The Landy Era” and hope to purchase a copy in the near future.

Speed and cadence in the long distances in regards to Marathon specialists and the shorter track trained runners; the reason Zatopek won the Helsinki Olympic Marathon was due to it being easier for him to execute a faster rhythm than it was for Jim Peters running the same speed. That’s why they say those who compete in the mile, 2 mile, 5K and 10k track races make better Marathon runners. While Peters and company struggle along, men like Zatopek cruise away, running faster with less effort. Carlos Lopes at the L.A. Olympics is another example of a track trained runner’s success in the Marathon. Track athletes like Herb Elliott and Lasse Viren executed this effortless flow in their races. Elliott easily establishing a huge lead with seemingly effortless fashion in the 1500 meters in 1960. In the late 1970s while in the military I competed in a half marathon held at Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. The favorite was Dr. Frank Day, a physician at my command who ran a couple of Honolulu Marathons and showed me his trophy he received for completing a 54 mile ultra marathon. Before the race Day and the other competitors trained long slow distances while I trained alone at a faster speed. When the race got underway I took the lead at the mile mark which was not my plan, and opened up a good distance from the field which I also had not expected to do. After the halfway mark I looked back and couldn’t see anybody. I was surprised. I guess my legs were so use to a faster pace the race, for a time seemed easier but it did become pretty tough the last two (2) miles. Dr. Day finished second. Forty-five minutes after the race I went in the bushes and threw-up.