With the Olympics just a couple of months away, it’s timely that we take a look back at some of the all time classic distance running contests that we have seen over the history of the Modern Olympics.

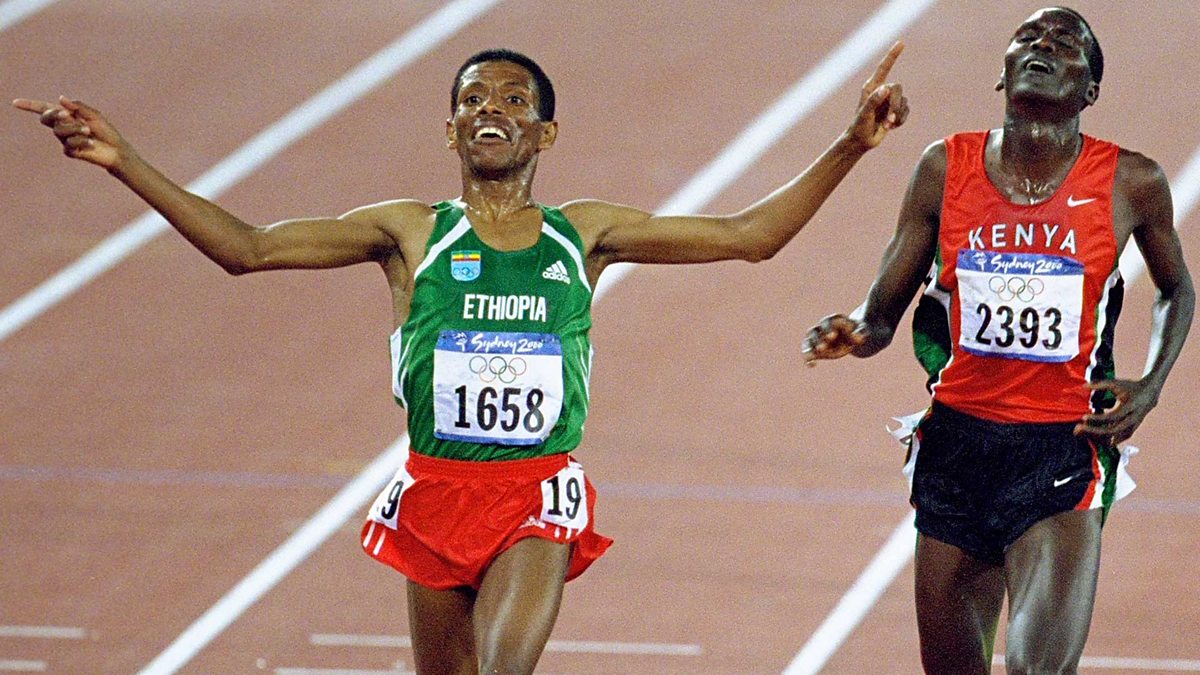

Here, we look at the battle between two of the all time greats, Paul Tergat (KEN) and Haile Gebrselassie (ETH), in the 10,000m Final at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney.

It took place on the 25th of September, a very special night, later referred to as ‘Magic Monday’, as it was one of the most spectacular nights of athletics ever seen.

For Australian fans, it was ‘Cathy’s Night’, the night that the legendary Cathy Freeman carried the weight of expectation of an entire nation and triumphed with a breathtakingly brilliant display to capture gold in the 400m and provide Australian fans with one of the very special moments of the Games.

Triple jump world record-holder Jonathan Edwards (GBR) finally won gold at the age of 34, in what was probably his last chance for Olympic glory and in the 5000m Sonia O’Sullivan (IRE) and Gabriela Szabo (ROM) fought each other right down to the line in an incredibly close finish. Szabo captured gold by a metre. Both women smashed the Olympic record by almost 20 seconds and Maria Mutola (MOZ) narrowly triumphed over Stephanie Graf (AUT) and future double Olympic Champion Kelly Holmes(GBR) in a very competitive 800m race.

Superstar Michael Johnson (USA) won his final major gold medal in the 400m, with a dominant display. The 33 year-old finished his glittering career as one of the all-time greats and British World Champion Colin Jackson missed his final chance for Olympic gold, running a disappointing fourth behind Anier Garcia (CUB) in the 110m hurdles and Aussie Tatiana Gregorieva thrilled the locals as she went close to upsetting American Stacey Dragila in the pole vault, winning a surprising silver medal.

Rounding out a fabulous night was the Men’s 10,000m that pitted two of the all time greats against one another in what turned out to be an enthralling tactical battle that ended in a sprint finish and one of the closest finishes in distance running history.

By the turn of the millenium, the 27 year-old Haile Gebrselassie had already established himself as one of the true legends of the sport and had achieved virtually everything in international distance running. He had broken 11 world records, from the indoor 2000m to the outdoor 10.000m and had medalled in the World Championships at 5000m and at the World Cross Country Championships and was a 4 time World 10,000m Champion (1993, 1995, 1997 & 1999)

He was also the reigning Olympic 10,000m champion. It was an extraordinary clash with Tergat in Atlanta in ’96, where a brave Tergat took the lead at the 8000m mark and attempted to burn off Gebrselassie with a series of 60-61 second laps, to no avail. He pushed the Ethiopian to the limit, being passed and losing ground to Gebrselassie at the bell, but closing the gap to 0.83 at the finish. Both men smashed the Olympic record (27.07.34 to 27.08.17 – shattering Brahim Boutayeb’s Seoul ’88 winning time of 27.21.46). What made this even more impressive was the 30 degree heat and 75% humidity they were dealing with on the night. Gebrselassie was also severely hampered by blisters, which prevented him from running the 5000m. The next two World Championship 10,000m races (1997 &1999) also featured the ‘big two’ slugging in out in warm, humid conditions in Athens ’97 and Seville ’99, with the tiny Ethiopian master coming out on top on both occasions.

For Tergat, now 31, Sydney was his last chance to beat Gebrselassie on the track at a major event. He planned to move to the roads and away from track and cross country after the games and would focus on the half marathon and marathon. Tergat’s strength was cross country. He had won five straight titles in the ’90s, beginning with Durham in 1995 and had established himself as the greatest cross country runner of all time – a few years before a young Ethiopian called Kenenisa Bekele would take over Tergat’s mantle. He said in an interview with Runners Tribe last year that cross country was the foundation of his success in the sport and it was where he knew he had the measure of Gebrselassie.

Tergat had excelled on the track, though he never achieved quite the same success as his mate Gebrselassie. Tergat had won – as mentioned – a silver medal in the 1996 Olympics, had finished third in the 1995 World Championships 10,000m in addition to his silvers in ’97 & ’99 and had run an impressive array of world class times from 3000m to 10,000m (7.28.70 for 3000m, 12.49.87 for 5000m and 26.27.85 – which was a world record when he ran it and is still 4th on the all time list – for 10,000m)

Though Gebrselassie and Tergat had developed a close friendship over the years, Tergat was desperate to win in Sydney. He had been outkicked by Gebrselassie in their four previous encounters in major championships, but here, Gebrselassie was possibly a little vulnerable. He had developed achilles problems that had persisted for more than12 months prior to Sydney and this had severely curtailed his preparation for his Olympic title defence. However, Gebrselassie was, like all champions, absolutely determined to overcome his problems and reclaim his title.

After a fabulous evening of athletics at its best, the 10,000m finalists took to the starting line. The two favourites were clearly Gebrselassie and Tergat, though a few other athletes in the field would potentially make things a little tougher for the two champions. Mohammed Mourhit was a Moroccan-born Belgian who was the reigning World Cross Country Champion, having taken Tergat’s title earlier in the year in a closely-fought race in Portugal, where the first three men – Mouhrit, Assefa Mezegebu (ETH) and bronze medallist Tergat were separated by just 2 seconds. He had proven track pedigree, having run some of the all time fastest performances for the 3000m (7.26.62), 5000m (12.49.71) & 10,000m (26.52.30) within the previous 12 months or so. Mezegebu was similarly well credentialled, having won numerous Championship medals already, despite being just 22. He also possessed impressive PBs at the 3000m and 5000m. Tergat’s Kenyan teammates Korir and Ivuti were, as one would expect, also pretty handy.

John Korir was another rising star at just 18, but did not yet have the credentials to be a serious challenger to the big guns and Patrick Ivuti was just 22 and lacked finishing speed. Both young Kenyans would make their presence felt on the biggest stage.

A University of Oregon alumnus, Britain’s Karl Keska, was somewhat of a journeyman, though was a very good cross country runner and had arrived in Sydney in good form. The rest of the pack were largely undistinguished, though the 34 year-old Burundian Aloys Nizigama would make an impact on this race early on, despite his best days being behind him.

Australians Shaun Creighton and Sisay Bezabeh, the young Ethiopian born athlete, failed to advance to the final.

The race began at a very solid clip and Tergat and Gebrselassie were content to settle in and just follow the pace. It was Nizigama who took the pack out at around 63-64 seconds per lap and they passed 1000m in 2.39.52, with the field already strung out in single file. Gebrselassie was in second, though not moving quite as smoothly as usual and Tergat was in about 4th, looking fairly comfortable.

The pace dropped off ever so slightly and a group of about 13 had separated themselves from the rest of the pack by 3000m (8.08.03), when Nizigama decided to move out and allow Ivuti to take on the pace. Gebrselassie and Tergat were both looking very good in 2nd and 3rd.

The pace began to lag, with Ivuti passing 4000m in 10.55.47 and Nizigama took the lead again and towed the field through halfway in 13.45.88 and Ivuti and Meb Keflezighi (USA) shared the lead through the 6th kilometre (16.31.19 split through 6000m). Ivuti and Gebrselassie slowed the pace and Nizigama reached the 7000m mark in 19.24.63. and the lead group had bunched up a little, with none of the major players willing to lay it on the line at this stage of the race.

Tergat took the lead briefly and then Korir went to the front and the Kenyas and increased the pace dramatically, with two laps in around 63. The lead group was now down to six. Korir led through 8000m in 22.04.46 and had Gebrselassie, Tergat, Mezgebu, Ivuti and Said Berioui (MAR) for company.

Korir maintained a steady tempo and the leading group passed 9000m in 24.44.09. The pack was down to five and Gebrselassie was tucked in behind Korir, with the tall, smooth-striding Tergat looking ominous, sitting just behind his great rival Gebrselassie.

Korir led on the penultimate lap, though the pace had not picked up much and, at the bell, the superstars Tergat and Gebreselassie gathered themselves for the final push to the finish. With 300m to go, Gebrselassie was poised on Korir’s shoulder, ready to pounce, with Tergat boxed in by Gebrselassie and Mezegebu.

With about 250m to go, Tergat pulled out into lane 3 and bumped into Ivuti and had to run wide to pass Mezegebu. Tergat accelerated hard and caught Gebrselassie napping and he stole a metre lead on his rval going into the final 200m. Tergat was really moving and he looked like he might finally upset Gebrselassie’s reign as King of the 10,000m, as Gebrselassie appeared to struggle.

Turning into the final straight, Tergat still held his one metre advantage, but the champion dug deep and began to close. With 50m left, Gebrselassie was almost level, but Tergat held on. Gebrselassie only drew even with Tergat with about 10 metres left and just inched ahead, leaning at the line, successfully defending his crown by the barest margins (0.09 of a second). Gebrselassie won gold in 27.18.21 to Tergat’s 27.18.30. As mentioned, it was the closest finish in an Olympic 10,000m race and the margin of Gebrselassie’ victory was less than that of 100m winner Maurice Greene’s margin of victory (0.12) over Ato Boldon.

Assefa Mezegebu was third in 27.19.75 and the young Kenyans Ivuti (27.20.44) and Korir (27.24.75) were 4th and 5th respectively. Mohammed Mourhit had dropped off the pace relatively early and failed to finish. He won another World Cross title the next year, but tested positive for EPO in 2002 and never achieved anything of note after his return from his two year ban.

On this very special night, this epic race was a clear winner with the crowd and global TV audience. It still stands up as one of the great Olympic distance duels. Gebreslassie covered the last lap in about 56.3 and the final 200m in around 25.9 to capture gold.

Tergat,on stage at last year’s World Cross Country Championships in Bathurst, spoke of the race as one of the defining moments of his career, despite his narrow loss. Gebrselassie also rates his Sydney 2000 performance as one of his best, given the obstacles he had overcome to get to the starting line.

In subsequent years, both Gebrselassie and Tergat continued to achieve at the highest level, setting new standards on the roads as they gradually moved away from the track.

Gebrselassie lost his World 10,000m title to Charles Kamati in Edmonton the following year, though his win in Bristol in the World Half Marathon Championships (1.00.03) signalled his determination to make his mark over the longer races.

Gebrselassie’s smooth transition to the longer road races continued. He made his marathon debut in London against Tergat and Khalid Khannouchi (USA) in 2002 and finished third in 2.06.35, behind Khannouchi’s world record (running 2.05.38 to Tergat’s 2.05.48).

He experienced another narrow loss to the new champion, countryman Kenenisa Bekele in the Paris 2003 World Championships over 10,000m, after another of the most gripping championship battles in history. Gebrselassie, attempting to run the finish out of his younger compatriot, covered the final 5000m in 12.58.8, but was outkicked by the supremely talented 21 year-old Bekele, who won the first of four consecutive titles at 10,000m.

Gebrselassie attempted to win his third consecutive Olympic 10,000m title in Athens 2004, but the ongoing achilles problems prevented him from training in the final few months before the Games. He was totally outclassed by his compatriots Bekele and Sihine and faded to 5th.

Upon recovering from his injuries, he achieved phenomenal success over the next few years, In 2005, there was a British all-comers 10km road record (27.25) and a world record the half marathon (58.55) in Arizona, where he destroyed an emerging young superstar, Sammy Wanjiru (KEN). He also ran an unofficial world best at 25km (1.11.37).

He ran a world 10 mile record (44.24) the following year, as well as winning the Amsterdam Marathon (2.06.20 – the year’s fastest).

After dropping out of the London Marathon in 2007, he ran a world 1 hour record two months later (21,285m) on the track in Ostrava and collected the 20,000m record (56.25.98) en route, to record his 23rd and 24th world records. He went to Berlin in September and smashed the world marathon record (2.04.26).

Missing his own record by less than half a minute in Dubai in early 2008 Gebrselassie turned his focus to the Berlin Marathon later that year, controversially deciding to skip the Olympic Marathon in Beijing. As an asthmatic, he feared the excessive pollution would hamper his chances and endanger his health

A 10,000m in a world 35-39yrs Masters record (26.51.21) and a sixth place Olympic finish (27.06.68) indicated he was ready for something very special in Berlin. He ran a phenomenal 2.03.59, breaking through the 2.04 barrier for the first time in history. This was one of defining moments of an already glorious career

He continued on for a few more years, running world 40 plus Masters world records in the 10 miles and half marathon (46.59 & 1.01.14) and continues to be involved in the sport at all levels, from being Ethiopian Athletics Federation President and having involvement in many community events. He is a respected elder statesman of the sport, who has also proved to be an astute businessman, taking the same work ethic from athletics to establish a thriving and very diverse business portfolio, which includes cinemas, a Hyundai assembly plant, ownership of a coffee plantation, resorts and hotels.

Though he’s a few years older than his sparring partner Gebrselassie, Paul Tergat continued to enjoy remarkable success on the roads. He had broken the world record for the half marathon for the third time earlier in 2000, and planned to focus on the marathon, looking to run fast times and, ultimately, to win gold in Athens in 2004.

He was second in his first three marathons (London in 2001 & 2002 and Chicago 2001) and was fourth in both Chicago 2002 and London 2003. The London 2002 was a big race for Tergat. He faced Gebrselassie and American Khalid Khannouchi, and Tergat finished second behind Khannouchi’s world record performance (2.05.38). Tergat was just outside Khannouchi’s old record, running 2.05.48.

It was in Berlin the following year where Tergat produced one of his greatest ever races. Following Sammy Korir’s excellent pacing, he became the first man to break 2.05 for the marathon, running 2.04.55, despite a wrong turn late in the race. Korir also snuck inside 2.05 (2.04.56) and almost pulled off an upset, as he decided to stay in the race and stuck doggedly to his countryman, with Tergat just pulling ahead in the last few metres.

A clear favourite in Athens 2004, Tergat had a disappointing race in the intense heat and humidity, where he looked good in the pack chasing Vanderlei de Lima (BRA) (who was famously shoved off the course by a protester), before losing ground to eventual gold medallist Stefano Baldini (ITA) after 30km. Baldini launched an incredible late race surge inside the last 10km to run down da Lima and win gold. Tergat eventually faded to 10th.

Tergat won in New York in 2005 and continued to be a top tier competitor until retiring at 40 in 2009. He has been a road race organiser and has, like Gebrselassie, managed to have a very successful business career.He has operated an import/export business, run a hotel and helped to start up a quarterly magazine about athletics. He was also an ambassador for the United Nations Food Program. He was a very welcome guest at the World Cross Country Championships in Bathurst last year, as official Ambassador for the event. His appearance on stage prior to the events, where he spoke fondly of the race in Sydney 2000, and the Q and A, which included Irish star (and honorary Aussie) Sonia O’Sullivan, was one of the highlights of the Championships.

Fans of distance running around the globe will recall the 25th of September 2000 in the Sydney Olympic Stadium, and the showdown between the two icons Haile Gebrselassie and Paul Tergat lives on in our memories as one of the very special clashes in Olympic history.